This article contains content potentially unsuitable for younger readers.

Tintin is gay! In 2016, a two-page spread publicized this theory in The Times. This claim around Tintin’s sexual orientation hinged on the following observation: the ginger-haired reporter is rarely seen in the company of members of the fairer sex. While we can’t really dispute this, there’s an explanation for it, one that sheds a rather unflattering light on a certain era of Belgian comic book history… Up until the end of the 1960s, a suggestion of an ankle, a hint of a woman’s knee or even a glimpse of cleavage were considered utter taboo. And there was no one to blame but the French.

What a life! He leaps from adventure to adventure, traveling across the world from Russia to the US through Tibet, and he even walks on the moon. However, his only companions are a snarky old alcoholic sailor, a pair of idiotic identical twins and a professor that we could mostly kindly characterize as… absent-minded! In the 24 volumes published starting in 1929, Tintin barely stops to give his dog Snowy a pat on the head. Clearly not a man of passion, then. But given the circumstances, what else could we expect? Of the 325 main or supporting characters who appear throughout the series, only about fifteen are women. And justifiably so! By the end of the 1960s, women—and overtly feminine women in particular—were pretty much banned from comics.

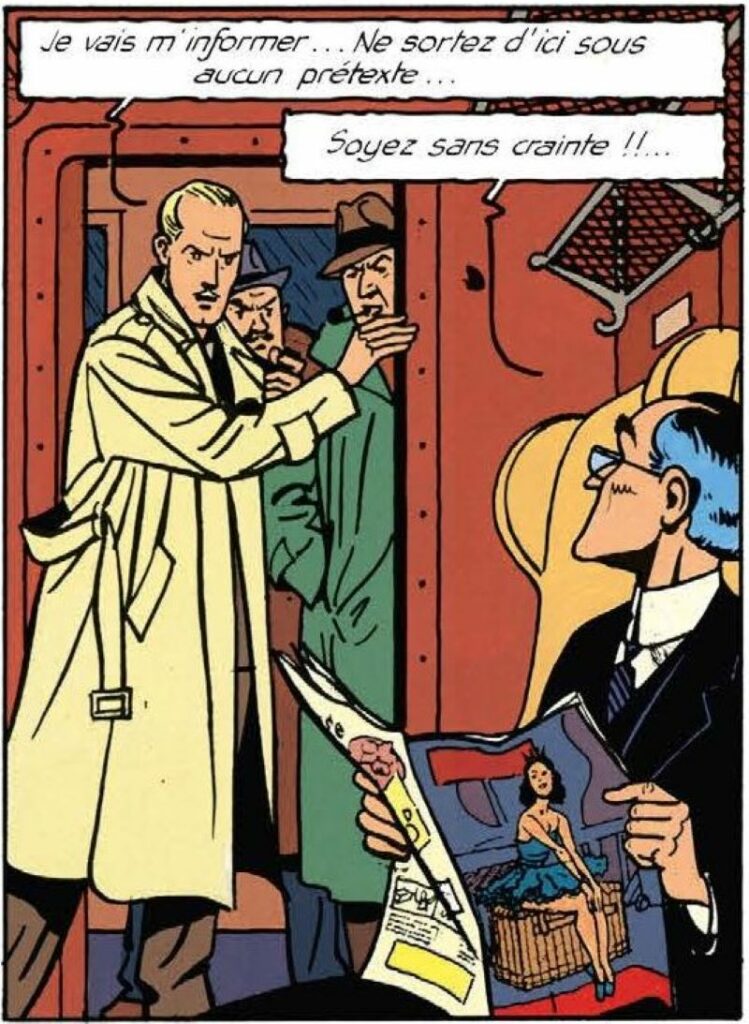

For this same reason, Jacobs’ classic Belgian series Blake and Mortimer was equally lacking in female representation. In 1953, when Jacobs started publishing The Yellow “M” in Tintin magazine, the readers were shown a single panel in which a supporting character read a magazine with a ballerina on the cover. That’s all it took for all hell to break loose. Note that the ballerina in question was featured wearing a completely acceptable outfit: a tutu. But the alleged eroticism—which was so minor it required eagle eyes to spot— resulted in grey bars being applied on top of the contentious image, so as to obscure it as much as possible. The commissioning editor was clearly trying to avoid giving the impression to Tintin’s young readers that Professor Septimus would read a girly magazine. Yet in creating this cover, Jacobs had drawn inspiration from an image printed in The Illustrated London News, the world’s first illustrated weekly news magazine. The decision to self-censor, in the end, was made internally, albeit very much dictated by the real fear of French censorship that had the potential to bring down the magazine.

How did the situation get so out of hand? This relentless censorship was largely influenced by the work of American psychiatrist Frederic Wertham, who was a huge critic of comics in his own country. His 1954 book, The Seduction of the Innocent, was dedicated to blasting American comics. A member of a censorship committee himself, he considered comic books to be poisoning young people’s souls. He set his sights on both writers and editors, especially after members of the Senate bent a favorable ear to his theories. To prevent the imposition of even more restrictive rules, the American comic book industry took a rush decision to establish its own Comics Code and thus regulate itself. It was a tide that was also felt over in Europe, with France taking the lead on the matter.

A few years before Wertham launched his campaign, the French were already implementing their own. The US efforts ended up being an unexpected but welcome support. That said, the French restrictions had other, far less virtuous, motives. The French could see that Belgian comics were doing well at the time. Perhaps a little too well for their taste. Simply put, the French did not take kindly to the Belgians’ commercial success.

A first attempt by the communists to ban all foreign comic books was unsuccessful. But, in another effort to boost its own comic book culture, France gave the green light to another proposal. On July 16, 1949, the Republic passed a law that was supposed to protect the country’s youth, but soon showed its true colors and revealed itself as disastrous for women’s representation in comics, even outside France’s borders. As in the US, a committee was established to control local publications intended for a young readership, but also to keep an eye on comics coming in from abroad. It spelled the end of artistic freedom for Belgian writers, who were effectively forced into self-censorship. Nine years later, the French protectionist law remained in force. The penalties on authors and editors had only become more onerous.

Drag queens

Later studies highlighted how women tended to be cast aside. One study showed that, between 1938 and 1963, only 43 female characters appeared in the pages of the weekly magazine Spirou. In that same period, 1,548 male characters had the same honor. Between 1948 and 1955, the number of female characters in Spirou was zero! The same study revealed that Tintin didn’t fare much better. Between 1946 and 1963, 134 women made an appearance, compared to 998 men.

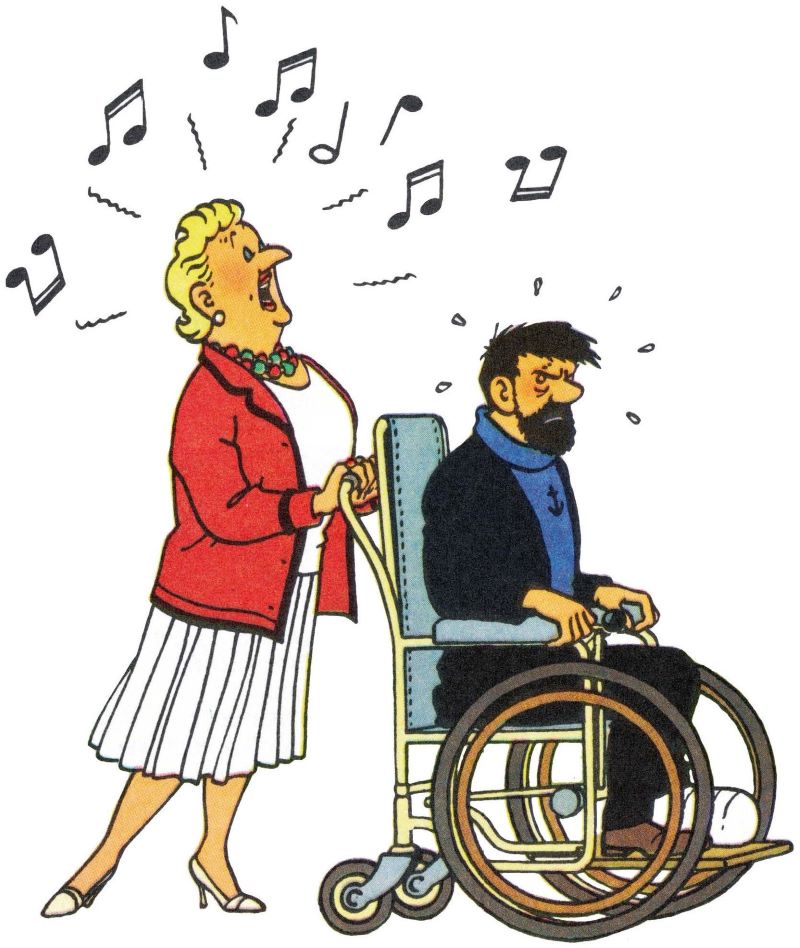

It’s striking too how the largely emancipated women of the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s were presented without a trace of sensuality. The representation of women was strictly controlled, subject to harsh guidelines. Comics at that time seemed to box female characters into three archetypes: the witch, the bitch and the tomboy. The two main female characters in Tintin ended up as a blend of these three archetypes. It was in the late 1930s that Bianca Castafiore, an opera singer, piped up. Literally. She comes across as a hysterical chatterbox who picks the most random moments to burst into song, grating her own vocal cords, as much as the nerves of her audience.

So is Tintin gay after all? Shouldn’t we first find out if Castafiore is actually a woman… or perhaps a transvestite? After all, she seems to lack any trait we usually attribute to grand old dames. She doesn’t even have a bosom! Instead, she wears something that we could—most charitably—call a breastplate. Hergé’s second notable heroine projects a blend of all three female archetypes. She’s somewhat incongruously given the sweet name Peggy and is married to General Alcazar, Tintin’s great rival. She cuts an authoritative figure, with her manly physique and pushy demeanor. That this kind of woman was portrayed as unattractive—typically with a hook nose—was very much in keeping with the trend at the time.

Stripping female characters of their femininity and reducing them to caricatures also made it easier to sidestep French censorship. Several writers did the same, and shrews abounded: unfashionably dressed elderly women, with skirts or dresses that fell way below the knees, or covered with a work apron. Women like this who had roles, albeit tiny ones, in the adventures of Tintin, were even more challenging to fit into more realistic series. It’s the main reason they are completely absent from the original stories of Edgar Pierre Jacobs’ Blake and Mortimer. We can scour the pages of Jacobs’ early stories and find only very few women.

Their appearance is limited to fleeting, barely discernible silhouettes. It’s not until 1960 that Jacobs dares to draw a woman—the medieval-era youngster Agnes de la Roche—in a small worthwhile role in The Time Trap. She even gets a few lines of dialogue. Jacobs goes further in the first few pages of the next volume, The Necklace Affair, by featuring women who are seductive and elegantly dressed. That said, these women remain mute and are relegated to one-time roles. “Blake and Mortimer was obviously not intended for a female readership and it was also being published in Tintin, which was a Catholic magazine,” explains Charles Dierick, ex-art director at the Comics Art Museum and member of the board of trustees at the Jacobs Foundation. “It wasn’t that Jacobs didn’t want to draw women. In The U Ray, the storyline he created before launching Blake and Mortimer, he included an important female character based on his wife. No one said a word! No doubt because The U Ray was published in 1943, in Bravo magazine. At the time, no one was worried about a French censorship committee.”

Dierick believes that Jacobs was singled out because Blake and Mortimer had become the highest-selling series in Western Europe in the 1950s. “Economically speaking, that had to be a thorn in the side for the French,” he says wryly, before hastily adding that censorship also came from the inside. “It was the devout Catholics who controlled literature intended for the youth. The editorial boards of Spirou and of Tintin were very much at the mercy of shady decision-makers who had input regarding drawings as well as storylines. The looming presence was powerful and could even be a defining factor. Falling out with the Catholic Church almost inevitably meant the loss of hundreds of thousands of readers. The clergy could easily send their cronies out into schools and remove weeklies that didn’t comply. It wasn’t a threat to be taken lightly. It was in fact an important weapon. They relied on moral values to win over young souls.”

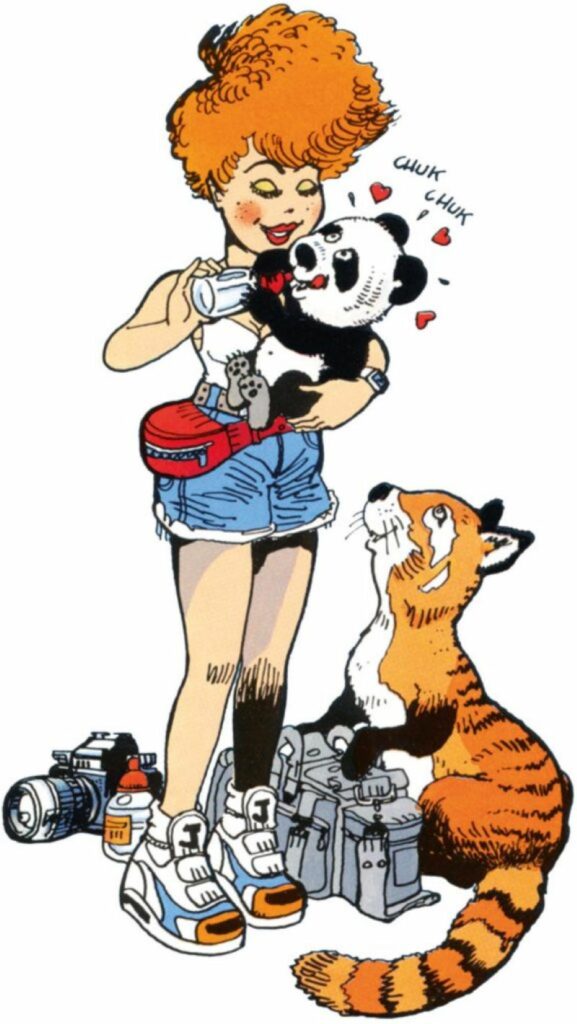

Seccotine

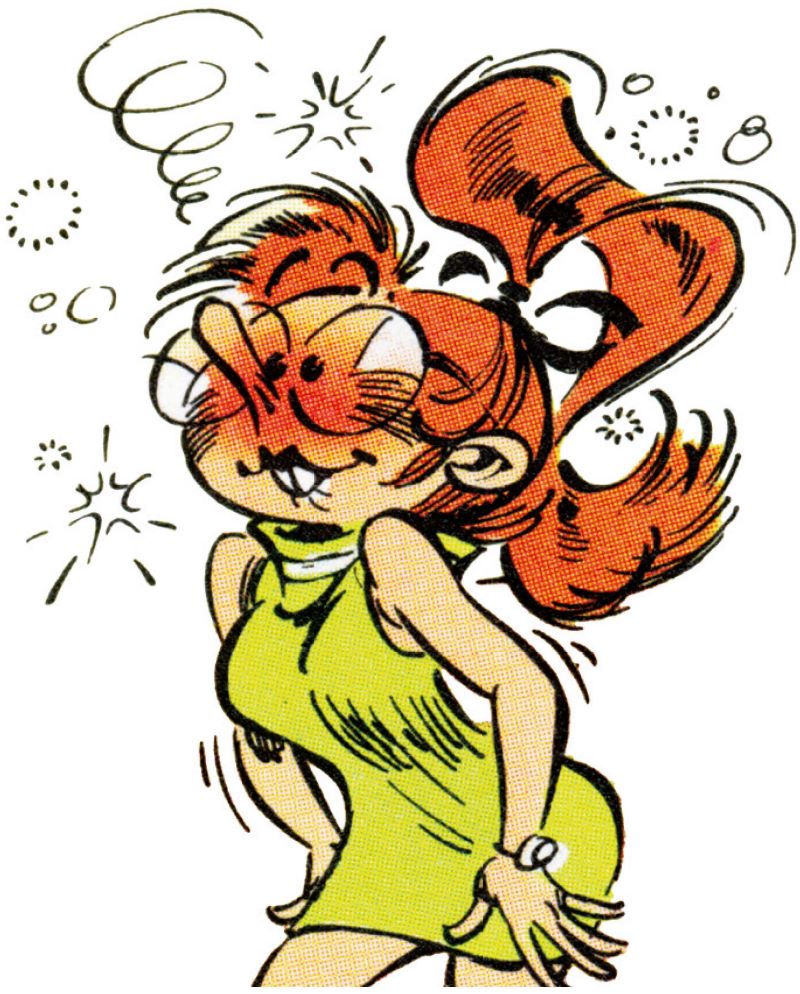

Franquin is one of the first French-speaking Belgian authors to give women leading roles in their series. In Spirou and Fantasio, he introduced the character of Seccotine, and then that of M’oiselle Jeanne in Gaston Lagaffe. Both were important characters. “He got away with it because the folks at Spirou were a bit more flexible and because Franquin himself was pretty important,” says Charles Dierick. Past that point though, he began to skate on thin ice. By the late 1980s, Franquin started using a page or two to openly address the love story between Gaston and Jeanne. As chaste as the romance remained, he’s still quite sure that “those scenes would definitely have been censored fifteen years earlier.” With M’oiselle Jeanne, Franquin brought more depth to the gags. Yet, Gaston’s showy sweetheart remained innocent and light-hearted.

Journalist Seccotine, however, receives better character development. Franquin described her as “a very special supporting character who has traveled a lot. Case in point, she’s been to Africa and turns out to be a lot smarter than both Spirou and Fantasio.” Still, the critics came down hard on our intrepid reporter, and by extension, on Franquin. “Seccotine was supposedly reckless while riding her vespa. Well, the old saying goes that women are bad drivers, which is not true at all. Pretty soon, I’m being called a chauvinist and getting a huge amount of criticism around Seccotine.

Comic books come under fire for crazy stuff. Take Boule & Bill (Billy & Buddy), for example… A committee of eight put out a whole series of articles to complain that I had depicted a female character as a homemaker. But then they turned around and criticized her for supposedly poking fun at men. Really, you can tear yourself apart trying to please everyone, but there will always be someone with cause for complaint.”

With all these restrictions, it became almost impossible to sneak new female characters into comics. The commissioning editors were just not having it, even when the characters didn’t show any cleavage. And speaking of the absence of bosoms: had Smurfette been created by a Frenchman and not a Belgian, she might have had a bust. “Back then, it was frowned upon to draw breasts,” confirms Nine Culliford, wife of series creator Peyo. “That’s why Smurfette looks more like a doll than a real woman.”

Smurfette, a cocktail of misogyny

In 1967, Peyo feels a rising tide of wrath from his female readership. Front and center is his wife. It’s all because of the list of nineteen ingredients Gargamel uses to bring Smurfette to life. The nineteen unflattering female characteristics include: “A touch of vanity, brains of an airhead, a bushel of gluttony, a handful of bad faith, a cube of foolishness, a hint of pride, a pint of desire, a portion of silliness and a portion of craftiness, and a lot of stubbornness.”

When she discovers this half-page scene in Spirou, Nine Culliford immediately brands her husband a misogynist. “I took issue with this list of flaws, mainly because we can also find many of these traits in men. For example, when Smurfette is hurt, the Smurfs all take turns to carry the stretcher to the Smurf village. Smurfette keeps telling them not to tilt left so much, not to go too fast, etc. Let me tell you that when my husband is in the passenger seat as I drive, he spends the whole time doing exactly the same thing. “Here, be careful, Nine. Now, take the left turn more slowly…” (smiles). Well, eventually I got used to it. It was a joke. Just a bit of fun.”

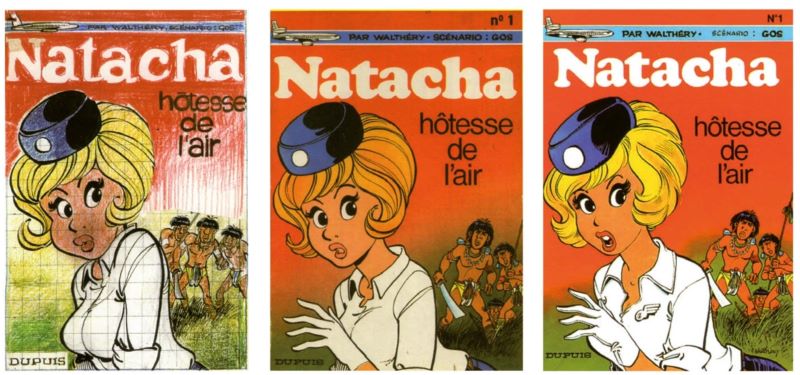

Natacha and Yoko Tsuno

In the late 1960s, as the censorship committee’s power and influence waned, and more progressive attitudes towards women’s rights began to prevail, Belgian commissioning editors nevertheless remained in the grip of conservative Catholic values. Writers were still being careful and self-censorship persisted. But change was afoot. 1970 saw a new dawn, in the form of an air hostess and a female electrical engineer. Their names? Natacha and Yoko Tsuno. Crucially, while they are attractive, they are equally intelligent, principled and feisty.

Yoko Tsuno, an unconventional heroine, was first shown in Spirou, a publication that was warming up to women’s liberation and feminism. By making the character an electrical engineer, Roger Leloup was taking a stand. But while Leloup quickly became a proponent of women’s liberation, not all followed in his footsteps. Walthéry for example, drew pretty girls because he liked pretty girls. Period.

The Japanese adventurer Yoko wasn’t the protagonist of the short stories in which she initially appeared, but Leloup—who, decades later, wrote: “she is my best friend, the one I never had”—quickly rectified the situation. “In fact, it was Charles Dupuis who, in 1970, insisted I make Yoko the protagonist,” the author remembers. “Not many believed in the series initially. The editors even thought I’d end up last in the annual readers’ survey on their favorite characters and series. Against all odds, I ended up in fifth place (smiles widely). That’s when they realized. After that, Dupuis not only wanted me to continue the series, but also to make Yoko the main character. It was a day I’ll never forget! So on page thirteen of the first long story, The Curious Trio, Yoko takes charge of the little group. Basically, this was because the first ten pages had been drawn prior to the survey.”

”Yoko Tsuno’s success made Hergé do a double take. Back when he worked as an assistant at Hergé Studios, Roger Leloup had tried submitting to his eminent employer a series draft that featured a female heroine. “‘Roger,’ Hergé told me, ‘women don’t belong in comics!’” Leloup gave up on changing Hergé’s clearly conservative mindset. But he persevered, with a storyline for Tintin that had initially been rejected by Hergé. “I had written a story for him about a lost civilization that lived on an island where lava was used to produce energy. But Hergé thought it was too advanced for Tintin… Years later, the rejected storyline was published as The Forge of Vulcan, the third long story in the Yoko Tsuno series. To be honest, I don’t think it was just the science fiction in the storyline that bothered him. There were too many female characters for his liking, and one was the protagonist! ‘Women only cause trouble,’ he said to me.

The real issue, according to Leloup, was that “while girls like Bécassine or Annie (La Petite Annie) were getting published, real female characters were falling by the wayside. By real, we mean women who were well-defined as characters. The ones who could get published couldn’t be too feminine to boot (unless of course a hand was modestly placed on the chest). And definitely no cleavage! That was pretty much the state of youth literature at the time. ISBNs were doled out by the French censorship committee, and editors were completely subject to its edicts. No ISBN, no magazine. Then again, the comics industry at the time remained quite small and very much Catholic.

That included Spirou. The editors tended to be very Christian themselves, which showed. They had the power to block sketches they didn’t like and even to withdraw entire magazines from circulation. The censorship was therefore very real, but it was clear that those who had to answer to the committee were mostly foreigners. While French writers were on the whole not bothered, Belgian editors, commissioning editors and artistic directors had to be wary of French censure. I remember what Hergé once said about Paul Cuvelier’s character, Line. He had drawn pleats in her skirt, which struck Hergé as too realistic, and therefore gaudy. But then I said I thought it was fine, and he backed off (smiles slightly). Anyway, it’s a very good example of the mentality of that era.”

Once these heroines began to see the light of day, self-censorship began to fade. “What we publish today is different from what we used to publish twenty years ago,” said Roba, creator of Billy & Buddy, in 2006. “The reader has changed. Spirou certainly remains a children’s magazine as it’s always been, but we have more freedom now. It’s still sweet and innocent, but there’s no more self-censorship. Natacha’s mini skirt would have been unthinkable back then. Self-censorship existed at the time at Dupuis. Some things were considered inappropriate for children.”

Respect

Heroines such as Yoko Tsuno and Natacha signaled the rise of women in comics. Slowly but steadily, female characters started playing a real part in these illustrated stories. Series like Les Panthères, Olivier Rameau and Mr. Magellan (and Capella) were published. Protagonist roles were just as likely to be given to women as they were to men. It was no surprise when Greg took the reins at Tintin. From day one, he made it clear he was going to put more women, real women, in the magazine.

In the mid-1970s, the rise of magazines like (À Suivre) and Pilote laid the groundwork for more modern comics that engaged in alternative discourses and were geared towards a more adult readership. Heroes became more relatable. The invincible hero made way for the antihero, an altogether more human character. Writers became more politically and socially engaged, ushering liberated women onto the scene. Female characters didn’t just proliferate in the world of comics, they also gained more visibility in series that had initially been male-centric.

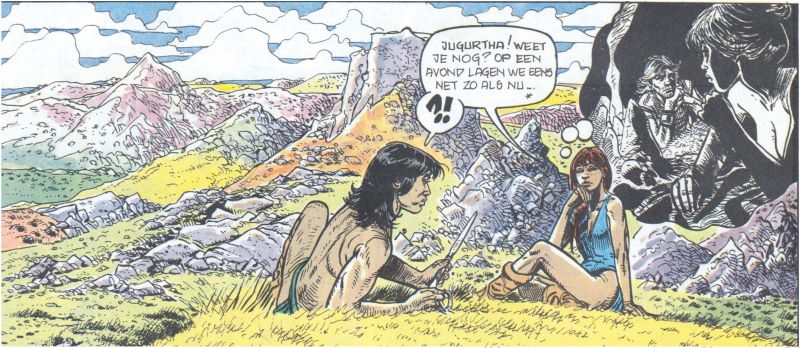

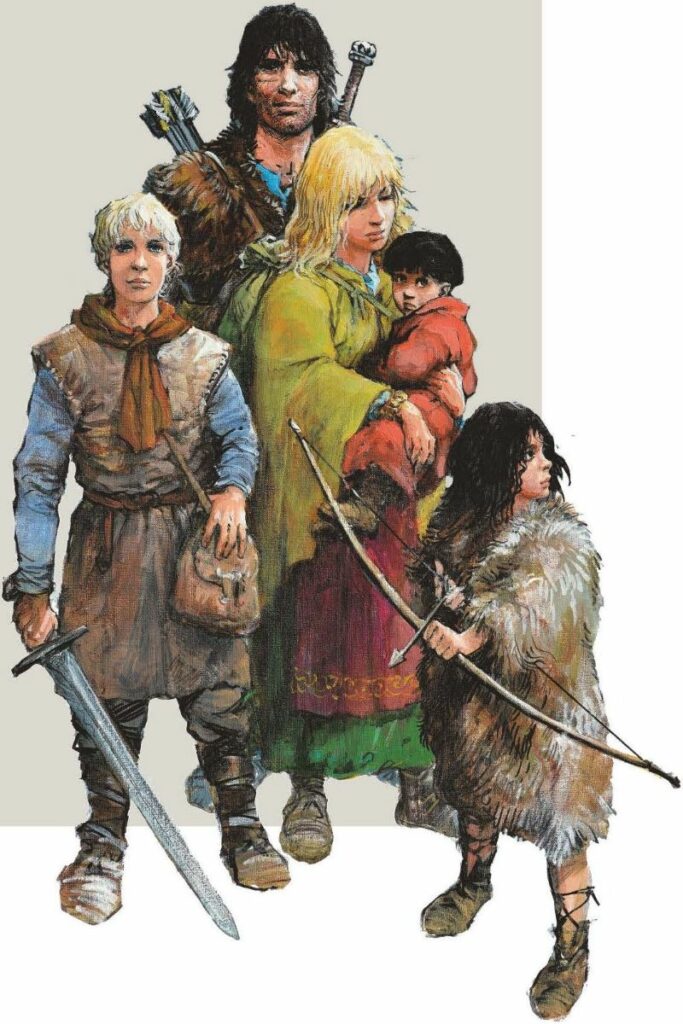

One such series is the Viking science fiction saga Thorgal (1977) written by Jean Van Hamme and drawn by Grzegorz Rosinski. Aaricia, Thorgal’s wife, became increasingly important as the series unfolded. And so their family grew. In that period, more and more women started headlining series, for example Comanche (1969), a western series by the Greg/Hermann duo and Jeannette Pointu (1982) by Marc Wasterlain. In the 1970s, red-haired Vania cropped up in the Jugurtha series. As series writer Jean-Luc Vernal confirmed, she was the first female character in a realistic comic who broke the mold by not being a supporting character; in fact, she became more popular than the male protagonists.

Erotica

But there are two sides to every coin. Some writers back then were not quite so taken by notions of feminism and persisted in objectifying women. We must note that 70% to 80% of comic book readers were male. It didn’t take long for certain writers and editors to put two and two together and realize that they could commercially exploit female sexuality, especially once they were free from the restrictions of a foreign censorship committee. From then on, the archetypes of witches, bitches and tomboys gave way to those of divas, little minxes and sexy girls. Female curves were highlighted and novelty comic books flourished with young women flaunting themselves on the cover, even if these characters played practically no part in the story itself.

Back then, women were advertisements. A sales pitch. One clearly intended for a predominantly male audience. As everyone knows, sex sells. So much so, that creator Jacques Martin (Alix), a man initially happy to go along with these new morals and mindsets, said the following in 1994: “Sadly the pendulum swung too far in the other direction: you could barely find a series without a naked woman on every page.”

That said, once these series left the pages of magazines and were published in full-length volumes, these books and authors, these pioneers of erotic comics, faced heavy opposition. In France, publisher Éric Losfeld, head of Éditions Terrain Vague, had wanted to give it a go. He was met with criticism however from religious groups and other moral advocates. His books were deemed dangerous. As a result, booksellers didn’t stock them and large retailers refused to distribute them. Ironically, this later made these titles cult hits in the comic book industry.

These cracks were precursors to the flood. Eroticism paved the way for something much more explicit. By the 1970s, comics had fallen into a real swamp of pornography. Under the guise of freedom of expression, countless overtly sexual titles emerged. Women were stripped of their personhood, and relegated to objects of lust. Early on, Sombrero, a Dutch publisher known for its clearly pornographic Zwarte Reeks (Black Series), tried, in its words, to bring more artistically erotic comics to the market, in addition to those which veered towards hardcore porn. It quickly became clear there was no appetite for the former. Hardcore porn alone ruled the market.

Censorship today

Nowadays, the censorship that hung over women in comics has practically disappeared. Some key exceptions remain. To be fair, these are minor, but they point towards the remnants of a certain kind of mentality. One example is the heavy-handed intervention of Belgian newspaper Gazet van Antwerpen in 1998 upon publication of Golden Gate, from the Largo Winch series. Artist Philippe Francq was dismayed to discover that a scene featuring three naked women and a man spread out on a bed was basically blacked out, instead of being cut. The scene had effectively been gagged: the girls were clearly too hot to handle, and seen as too provocative for the publication’s readership.

This also held true for the women in XIII, another series written by star scriptwriter Jean Van Hamme. He loved featuring beautiful lesbians in key roles. How much of it was on purpose though? “Listen, I’ll give you the thinking behind it,” says Van Hamme. “At some point, Largo needed a new private pilot. Why not make the character female? If she’d been straight, we would immediately face issues: like all women, she’d inevitably succumb to Largo’s irresistible charms. Making her a lesbian had a twofold advantage: on the one hand, she wouldn’t try to seduce the protagonist, and on the other, she’d butt heads with Simon, Largo’s best friend, who tries to bed every woman he sees. It would be hilarious. Just picture it, Simon does everything to try seduce her, but his prey decides she’d rather spend the night with another woman. So that makes it a double whammy… And the sex? Ok, let’s not go overboard. I didn’t have an agenda to introduce lesbians or any other particular social group into the series. It was just a practical solution at the time. And it was written in a way that made it clear it was not meant to be taken seriously.”

These days, readers have become used to Sapphic love scenes. Not only in Largo Winch, but also in other adventure series, such as XIII or Jessica Blandy (first published in 1987). It’s as if these kinds of scenes have become the specialty of scriptwriter Jean Dufaux, who authored Jessica Blandy, and even more so of Jean Van Hamme. Readers need look no further for trademark lesbian scenes than Van Hamme’s adventures of Lady S and Thorgal. And ultimately, what is the goal of such scenes? The desire and fulfilment of straight men.

Scriptwriter Jean Dufaux, however, sees himself differently. He doesn’t shy away from putting sexy women in the driver’s seat of certain series, of course, and he also treats sexuality as a key theme in his writing. Beyond that, it’s easy to see how strong and liberated his main female characters tend to be, such as those featured in Jessica Blandy, Raptors or Djinn. At the same time, they are as likely to act on lesbian impulses as they are to objectify themselves and play into the male gaze. Dufaux maintained that this behavior was in fact reflective of the zeitgeist, and defended his choices in a 2004 interview.

“Liberated as they may be, these women still live in a man’s world. It’s just the way it is. Too often they are blocked from taking on responsibilities. It’s crushing, really. They still have a long way to go… Also, I think it’s interesting to see how someone can find themselves in trouble while trying to help others, as it happens with Jessica Blandy. In Djinn, I yet again explore the story of a young independent woman, who has ended up in a harem. She becomes a slave, but that just makes her stronger. Then she finds love and becomes a free woman again. She refuses to belong to a man, even one she loves. I’m interested in this duality. I’ve always said that Jessica Blandy is one of my most optimistic series, a statement that consistently shocks my readers, but, despite everything we’ve thrown at her, Jessica still believes in herself, in a world that’s slipping away.”

A real hero never gets married! That said…

“Look, someone discovering The Adventures of Alix at the age of twelve or thirteen, around the time I got to know Tintin, is basically still a child,” said Martin in a 1976 interview. “Boys couldn’t care less about girls at that age. But take the same reader at nineteen or twenty years old, and he’ll start wondering: “How come Alix doesn’t have a girlfriend?” Or “How come we never see Lefranc with a pretty girl?” And at twenty-four, twenty-five, he’ll wonder whether the hero will ever get married. But I think that’s a big mistake. I firmly believe a hero should never get married. When someone gets married—I’m not against marriage by the way, I am married myself—they are no longer free to go on adventures. Other things become a priority: money, taxes, putting food on the table… They can hardly leave everything behind for six months to go to Australia. It’s just not done.”

In the mid-1990s, Martin drew parallels with action-movie stars such as Indiana Jones and James Bond. “You’ll see a different love interest in each new movie, but no commitment. If the hero settles down, it would inevitably mean the end of going on adventures.”

But not everyone agreed. Quite the contrary. Jean Van Hamme was the scriptwriter to break with convention. In Thorgal, he shattered the image of the traditional lone hero. The Viking married his beloved Aaricia in the third volume, and she bore him a son, Jolan, in the next one. They also went on to have a daughter. “I hadn’t really planned the marriage. It just happened,” said Van Hamme. “Aaricia could have stayed as Thorgal’s perpetual fiancée or, just as easily, she could have disappeared in the following volume. But I went another way. Thorgal’s main plot is centered around a couple and not a conventional lone hero.” That said, he acknowledged that the direction he took sometimes meant he had brought trouble on himself.

Nevertheless, the scriptwriter is sure that Thorgal owes a great deal of its popularity to the “desire for a peaceful family life and love towards one’s children. Love, it’s always love. Thorgal is proof of that, despite our hero engaging in certain amnesia-related escapades. The series is imbued with a sense of morality—I’d even call them Christian values—which ties things together. I am an atheist myself, but due to my cultural background, I always carry in me a bit of Christian heritage. There is magic and mythology in the goings on, which is what draws readers in, but so do these values.”

TO BE CONTINUED IN PART II

Excerpt from La Belgique dessinée, by Geert De Weyer (Ballon Media, 2015).

Translated by Storyline Creatives.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily represent the views of Europe Comics.

Header image: [Liberty Leading the People] © Dany