One of very few major female figures in the world of comics, Claire Bretécher is the astute observer of the social and political changes her generation faced, her work conveying their effect on human relations; at work, in the family, relations between genders,  races and social classes, relations created by friendships and through sex. Despite addressing the society of her generation, newer readers find her work just as relevant today as it was during Bretécher’s most prolific years in the 70’s and the 80’s. Named by Roland Barthes (literary theorist and critic) as France’s best sociologist, Claire Bretécher exceeded not only as a comics creator, but also as a multi-faceted artist, demonstrated by her work outside the comic strips, most notably by her sensitive portrait paintings.

races and social classes, relations created by friendships and through sex. Despite addressing the society of her generation, newer readers find her work just as relevant today as it was during Bretécher’s most prolific years in the 70’s and the 80’s. Named by Roland Barthes (literary theorist and critic) as France’s best sociologist, Claire Bretécher exceeded not only as a comics creator, but also as a multi-faceted artist, demonstrated by her work outside the comic strips, most notably by her sensitive portrait paintings.

After a dull, Catholic childhood in Nantes, Bretécher moved to Paris. Having dropped out of her Fine Arts studies, she introduced her work to the world by producing illustrations for various newspapers. In 1963 she was approached by Goscinny (French comics editor and writer, internationally known as the creator of Astérix) with an offer to illustrate Le Facteur Rhésus (Rhesus Factor) saga, which he intended to publish in L’Os à Moelle magazine. As Bretécher recalls it – it was an offer she couldn’t refuse, however he asked her to draw things she didn’t know how to draw at the time, which Goscinny was not exactly pleased with.  After Bretécher went on to freelance for magazines such as TinTin and Spirou that were vigorously going through their revival period. An unimaginable place for a woman at the time – Bretécher had entered the all-male world of comics, right at the heart of humour renaissance in France.

After Bretécher went on to freelance for magazines such as TinTin and Spirou that were vigorously going through their revival period. An unimaginable place for a woman at the time – Bretécher had entered the all-male world of comics, right at the heart of humour renaissance in France.

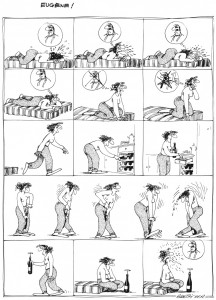

More experienced, in 1969 she again accepted Goscinny’s offer to collaborate – this time in the prestigious Pilote magazine. At Pilote she began working on Cellulite – the character of a medieval princess who was a true feminist before her time. The charac ter and the series, as many French strips at the time, were influenced by American daily strips, in particular those created by Johnny Hart, while Bretécher’s later work was inspired by another American satirist, Jules Feiffer. She afterwards started moving away from the simplicity of these drawings towards a more realistic style. In 1972 she got an offer from her colleagues at Pilote – Nikita Mandryka and Marcel Gotlib – to join them in starting a new magazine – L’Écho des Savanes. With its first issue entitled Réservé aux adultes (For adults only), and just like similar French “underground” magazines of the time – L’Écho des Savanes was a daring and dark X-rated publication. There, her stories became increasingly hard-hitting, which became a huge part of Bretécher’s identity as a comics creator. Throughout her entire career, she never gave up on the un-compromising approach towards the subject of her work. However cruel or tender, Bretécher’s strips always remain bitter and lucid.

ter and the series, as many French strips at the time, were influenced by American daily strips, in particular those created by Johnny Hart, while Bretécher’s later work was inspired by another American satirist, Jules Feiffer. She afterwards started moving away from the simplicity of these drawings towards a more realistic style. In 1972 she got an offer from her colleagues at Pilote – Nikita Mandryka and Marcel Gotlib – to join them in starting a new magazine – L’Écho des Savanes. With its first issue entitled Réservé aux adultes (For adults only), and just like similar French “underground” magazines of the time – L’Écho des Savanes was a daring and dark X-rated publication. There, her stories became increasingly hard-hitting, which became a huge part of Bretécher’s identity as a comics creator. Throughout her entire career, she never gave up on the un-compromising approach towards the subject of her work. However cruel or tender, Bretécher’s strips always remain bitter and lucid.

In 1973 Bretécher left L’Écho des Savanes after accepting an offer from the left-wing socio-political magazine Le Nouvel Observateur, where she started her now legendary weekly strip La Page des Frustés (The Frustrated) that satirised the lifestyle of the magazine’s readership, those now known as the “bourgeois bohemians”. This was a significant career move for Bretécher as it gave her work access to a more general public. An outstanding interpreter of her time, Bretécher soaked up the existing mood and exposed the tension between the permanence of the determined moral order and the desire for profound change while using her great sense of humor and her free tone.

The success of Les Frustrés pushed the artist to embark on an exciting but exhausting adventure of self-publishing. Between 1975 and 1980 she published her earlier work as well as the five albums of Les Frustés. Since 2006 the majority of this as well as Bretécher’s later work is being reissued by Dargaud

The success of Les Frustrés pushed the artist to embark on an exciting but exhausting adventure of self-publishing. Between 1975 and 1980 she published her earlier work as well as the five albums of Les Frustés. Since 2006 the majority of this as well as Bretécher’s later work is being reissued by Dargaud

Les Frustés was followed by Le Destin de Monique (Monique’s Fate), an almost futuristic work for the year it was released (1983), also exploring technical assistance for procreation, legalisation of abortion, questions of sexual identity, notably, introducing a transgender character to the story.

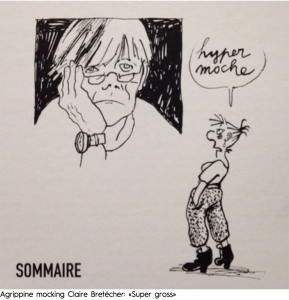

Bretécher’s most beloved character, however, remains Agrippine (Agrippina). A superb prototype of a teenager – lazy, moany and narcissistic – Agrippine battles through the of adolescence with a fierce attitude and an absolutely delightful dark humor. Agrippine later came to life in a series of 26 cartoons broadcasted by Canal+ in France. Agrippine was first translated into English by Europe Comics in 2016.

Winner of Angoulême Comics Festival’s Anniversary Prize, Claire Bretécher once said,“If the ideas come quickly, the change will come slowly.” The famously discreet artist, often named the biggest “comedian-sociologist” of the ninth art, never associated herself with any ideologies or sociological theories. And if her stories make us laugh, it is because we recognise our own ambiguities in them.

Winner of Angoulême Comics Festival’s Anniversary Prize, Claire Bretécher once said,“If the ideas come quickly, the change will come slowly.” The famously discreet artist, often named the biggest “comedian-sociologist” of the ninth art, never associated herself with any ideologies or sociological theories. And if her stories make us laugh, it is because we recognise our own ambiguities in them.

Until February 8, 2016 Centre Pompidou in Paris is hosting an exhibition dedicated to the work of Claire Bretécher.