In search of the first graphic novel

In Europe, particularly in Italy, comics were long designed for and targeted at a male audience of young boys and teens. Comics in book format weren’t entirely absent from the Italian publishing landscape before the Second World War, but they were mostly editions printed by bookshops with Disney-type stories and often marketed as gifts. In the eyes of historian Gianni Bono, Le burle di Furbicchio ai maghi (1924) was the first Italian comic, while professor Fabio Gadducci dared to move the birth of the Italian graphic novel all the way back to 1870, the year when Pasquino all’Istmo di Suez by Casimiro Teja was published.

In any event, since their origin, Italian comics have always relied heavily on foreign production, particularly American. Even popular Italian series like S.K.1 (1935) and Ciclo della Malesia (1936) by Guido Moroni Celsi, Saturno contro la Terra (1936) by Federico Pedrocchi and Giovanni Scolari, and other series that are explicitly linked to the Fascist regime (e.g. Romano il Legionario by Kurt Caesar, 1938), borrowed from the narratives and stylistic canon of American comics.

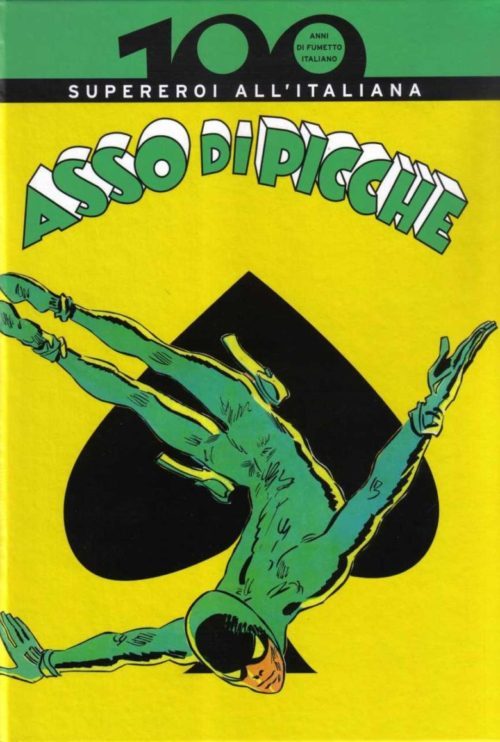

This landscape didn’t change overnight at the end of the Second World War. Asso di Picche, a character created in 1945 by Mauro Faustinelli, Alberto Ongaro and Hugo Pratt, could be considered the first Italian superhero. Dressed in yellow tights that hide the identity of the lazy journalist Gary Peters—like Batman and Superman—the avenger Asso di Picche (“Ace of Spades”) fights international crime. But the influence of Milton Caniff and his Terry and the Pirates is easy to see in the still-immature style of Pratt, the future creator of Corto Maltese.

The anthology in which the character was first introduced—Albi Uragano—took the name of its main character, but after twenty issues it went out of print. When the Italian editor Cesare Civita emigrated to Argentina following the introduction of racial laws in Italy and bought the rights to the headline characters for his own Editorial Abril, he also suggested the authors move to Buenos Aires with him. It was then that the so-called “Venice Group” split in two. Those who left, including Pratt and Ongaro, came into contact with local Argentinian authors such as Héctor Germán Oesterheld, who would later create El Eternauta (1957-59). A few years later they founded a true Italo-Argentinian school of comics that would inspire a new generation of comic book authors.

The fumetto nero

The 1960s were a particularly interesting and fruitful period for European comics. It was during this decade that the comic book became a widespread phenomenon. In Italy, events seemed to be conspiring to push comic books into the public and critical spotlight. It was in 1962 that readers were introduced to Diabolik, a character and antihero par excellence partly inspired by the fictional hero Fantômas.

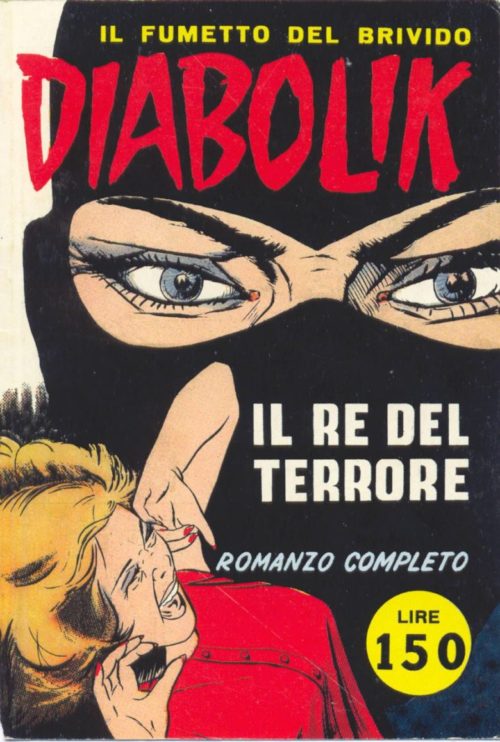

A thief of exceptional abilities, a master of disguise, and a ruthless assassin, depending on what the situation called for, the character in black tights created by the Giussani sisters was something completely different from any other hero that had ever stepped out of the pages of adventure comics. On the cover of the first issue of Diabolik (Il re del terrore, or “The King of Terror”) was the mention, romanzo completo (“complete novel”), and for good reason. It did indeed look like a novel. The Topolino (Mickey Mouse) pocket book format, published by Arnoldo Mondadori Editore starting in 1949, had set the precedent for novel-sized comic books. Over time, this format would become a point of reference for many notable imitations, such as Braccio di Ferro (Popeye), Tiramolla (Roll-Spring) and Geppo, often created by the same authors working on Disney characters elsewhere. However, in most cases, these were anthologies. The stories of Diabolik were mostly resolved in single issues: narratives of a certain length that could stand alone, even if they could technically be considered serials, with some recurring characters and situations.

If Fantômas became a favorite of the surrealists because the stories of his cruelty, lust and anarchism were never wrapped up in a happy ending, Diabolik was the bugbear of conformists and educators who couldn’t put up with his lack of principles.

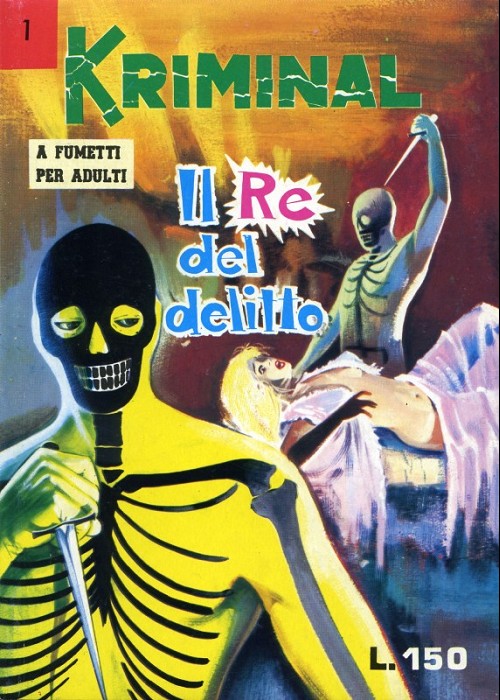

Diabolik shocked the paternalistic, moralistic and prudish publishing industry of the time and in so doing launched the so-called fumetto nero phenomenon (literally “black comic”). The success of the fumetti neri, which often had the letter ‘K’ somewhere in the title—e.g., Kriminal, Satanik, Zakimort, etc.—managed to scandalize representatives of the Catholic Church and political organizations across the board. Even the Italian parliament spoke out against the comic.

These imitators of Diabolik, which happens to be the only fumetto nero still published today, exploited the most sensational features of Angela and Luciana Giussani’s character, amplifying the effects: sadism replaced violence and subtle eroticism became sex verging on the pornographic. Many of these comics were translated and sold well abroad, especially in France. Some famous contemporary authors even learned the ropes from working on these productions, often thrown together hastily and badly printed. The Italian fumetti neri were in fact marketed as comics for adults (even if they were often read by teenagers as well). However, the “for adults only” and “not for sale to minors” warnings on the covers weren’t enough to placate the most zealous moralists, whose beliefs and prejudices finally managed to gain the upper hand. Their indignation often led to court cases and some publishers were even forced to close their doors.

Despite the questionable value of the individual products, these comics were considered a modern and unifying phenomenon that brought pre-war productions up to date: in many ways they were more in line with contemporary public taste, as readers had already moved away from what educators and teachers were proposing at the time.

The Bonelli format

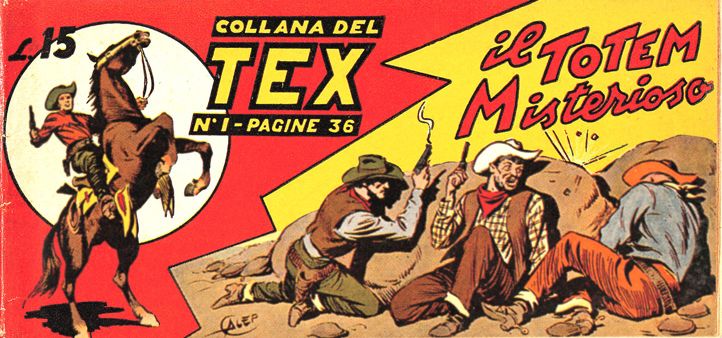

The story of the Bonelli format is similar to what happened in the United States. Tex (1948), Bonelli’s first great success, was originally published as a comic strip (16.5 x 9 cm). The profits from these publications were then used to produce stories known as raccoltine (“little collections”). In 1954, the first attempt at a chronological series in comic book format was made, but it was only from 1958 on that the “Bonelli format”—100-page comic books measuring 16 x 21 cm—was adopted.

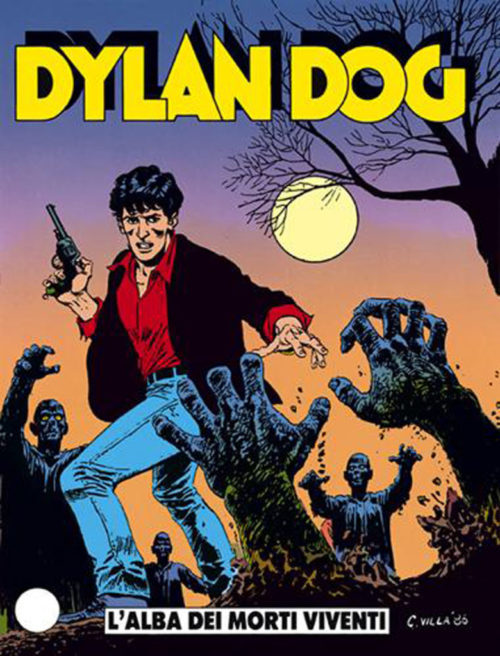

Especially after the great success of the Dylan Dog series, the format became so successful that the market was invaded by “bonellidi,” or comic books from other publishing houses printed in the same format as the Bonelli comic books that often mimicked their style and structure. Not really a pocket book like Diabolik and the other fumetti neri, the Bonelli format was distinguished by its page count—100 as opposed to the 48 of the Franco-Belgian format—which allowed serialized narratives more breathing room. As had happened with Diabolik and the French graphic novels, both commercial and social factors led to the adoption of this particular format, the most successful in Italy and one of the most successful worldwide.

Sergio Bonelli remembered the genesis of his publishing house’s pocket book format like this:

“My mother Tea and I realized that the public was changing, that it wanted a longer read than what was being offered by comic books of the time, that people had more money and therefore could indulge in something more sophisticated. We also realized that people no longer wanted to wait a week to read a story that would take them just a few minutes to finish.”

Bonelli’s serial structure allowed for greater stylistic and narrative variation and a more varied product than what was being produced by other commercial publishing houses at the time, American superhero comics included. Bonelli always aimed at the immediate recognizability of its products, stamping its books with a style that was its strength, but at the same time its greatest limitation. Regardless, the Bonelli style undoubtedly set the standard for comic books in Italy. Given its strong position in the Italian comic book market, the Bonelli comic book became a benchmark for many other publications, which rarely, however, experienced comparable success.

Continue to Part 2

From Graphic Novel: Storia e Teoria del Romanzo a Fumetti, by Andrea Tosti (Tunué, 2016). Translated from the original Italian by Storyline Creatives.

Header image from Diabolik © Giussani / Astorina