The era of Italian magazines: rise and fall

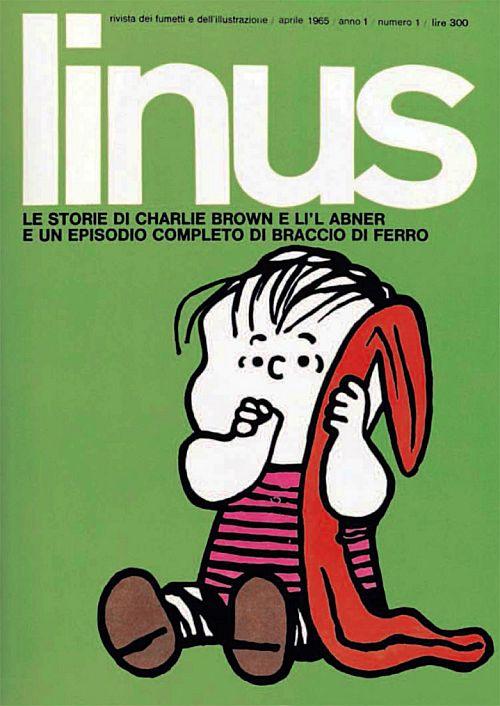

The magazines published in Italy from the mid-‘60s onward played a crucial role in paving the way for the acceptance and promotion of a new type of contemporary, more sophisticated comic book. The first real magazine dedicated to the “adult” comic book was Linus, first published in 1965 by Giovanni Gandini.

Crepax and Lunari were the first two Italian authors to appear in the pages of Linus, which was initially inspired by foreign—mostly American—comics, which were the sole focus of critical attention at the time. But Linus was also to become a haven for many authors, contemporary and future, who found there the space and opportunity to write about their own work. In subsequent years, political issues and current events would appear as comics in the magazine’s pages almost in real time.

Linus was followed by a number of competitors and imitators. The second half of the ‘70s saw the launch of two new weekly titles, Lanciostory (1975) and Skorpio (1977), by Editorial Eura (now Editorial Aurea), which initially featured the work of South American authors before opening up to the Franco-Belgian market.

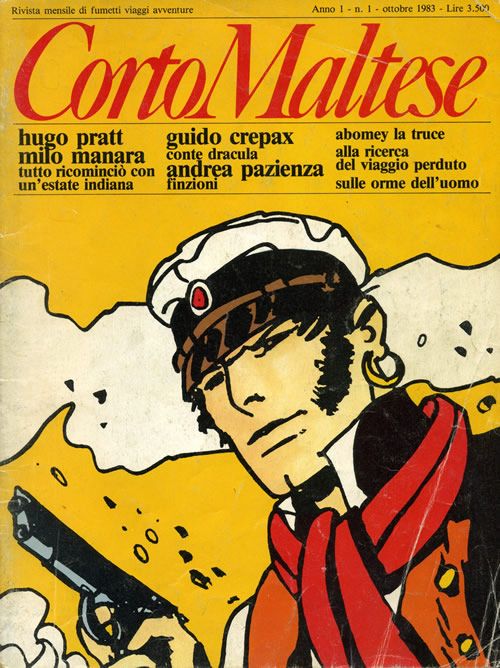

The ‘80s were perhaps the most fruitful years for Italian comics. Many new magazines were published, including Totem (1980), much of whose material had previously appeared in Métal Hurlant (an Italian version of the French magazine was published in the same year); Corto Maltese (1983), which published primarily Italian authors; L’Eternauta (1980), which initially concentrated on Argentinian and Spanish authors; and Comic Art (1984) by the same publisher. The success of these magazines soon began to wane, however, partly due to competition from commercial television and partly due to a renewed interest in popular comics.

The ‘90s saw some interesting, albeit short-lived, projects. The monthly Nova Express by Granata Press managed to remain in print from 1991 to 1993, despite a slew of difficulties. Nero, another Granata magazine, was published from 1992 to 1994. The monthly Kappa Magazine, specialized in manga, was more successful (1992-2006) thanks to the great popularity Japanese comics enjoyed in Italy at the time, and the fact that the magazine was serialized. The arrival of Zero (Granata Press), the first magazine in Europe completely dedicated to Japanese manga, dates back to 1990.

Among the longest-lived magazines of the decade, Mondo Naïf (Star Comics, 1996) was particularly important for its promotion of new talent in Italy, and Il Grifo (1991-1995) was effectively an art magazine dedicated to comics. By the mid-‘90s, the comic book had become entrenched in Italian culture. The comic book had become art. The fact was no longer in doubt. Comics could now speak for themselves.

The decline of the comics magazines, which continue to struggle to find stable footing in the editorial market, has also marked the partial abandonment of the short story form. From the mid-‘90s onwards, long-form stories came into vogue, above all the graphic novel.

Publishing houses and the graphic novel

At the end of the 1990s, when the age of magazines was drawing to a close, a number of publishing houses sprung up and played an important role in transforming the comic book into a commercial product. In 1996, thanks to Andrea Plazzi and Edoardo Rosati, Edizioni PuntoZero was born, which aside from publishing essays on cinema, animation and comic books, also published work by different comics writers. When PuntoZero closed in 2001, its catalogue was taken over by Kappa Edizioni.

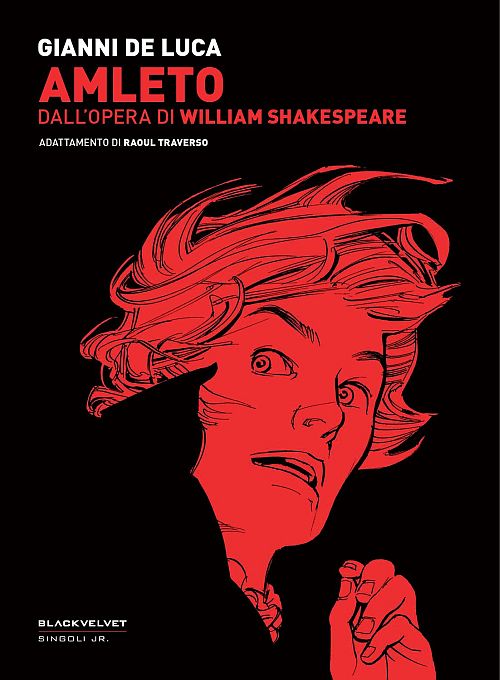

Black Velvet was created in 1997 by Omar Martini and Luca Bernardi. The publisher first distinguished itself by focusing on the American market, before opening up to other countries’ authors as well (for example, Scandinavia with Jason, Spain with Max, New Zealand with Dylan Horrocks, and Switzerland with Thomas Ott), while at home it promoted Italian authors like Massimo Giacon, Alessandro Baronciani, Paolo Bacilieri, Massimo Semerano, Alberto Corradi, Otto Gabos and others.

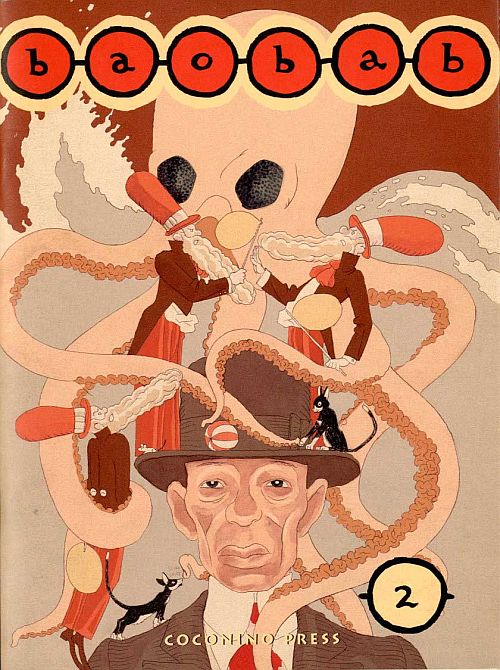

Comic Art, la rivista dello spettacolo disegnato published its last issue in 2000, marking in many ways the end of the era of the comics magazines. The future of this medium was clearly in book format. The same year, Coconino Press was founded in Bologna by comic book artist Igort (Igor Tuveri), distributor Carlo Barbieri, and businessman Simone Romani. The name they chose immediately suggested the mission of the publishing house. Coconino County in Arizona was the backdrop for the surreal adventures of Krazy Kat by George Herriman. With a focus on foreign creations and a high level of editorial attention, Coconino Press was a real comic book author’s press. Thanks to the extensive network of contacts amassed by Igort throughout his career, Coconino launched numerous international co-editions.

Coconino Press grew quickly and today publishes more than twenty collections. Its objective was and remains clear: to move beyond the newsstand to specialized comic book stores and even bookstores.

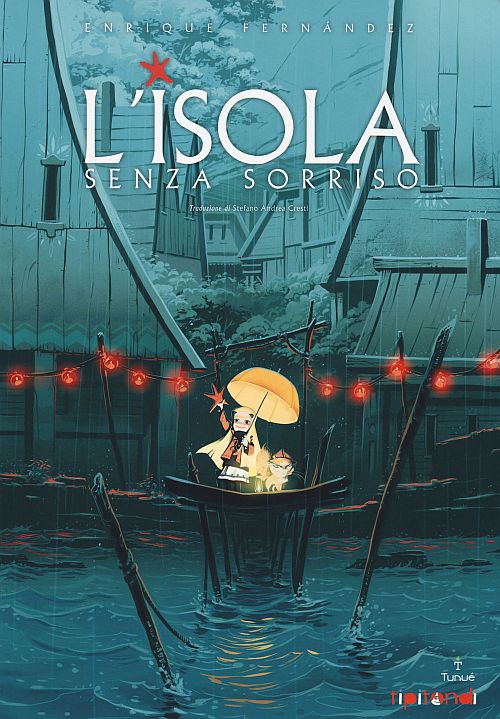

The Latina-based publishing house Tunué was founded in 2004 by its current publishing director Massimiliano Clemente and manager Emanuele Di Giorgi. Tunué initially specialized in essays about comics and visual imagery, but very quickly filled its catalogue with its own graphic novels. The first volumes of the series Graphic Novel were mainly created by young Italian authors, some just starting out, but very soon international authors filled out the ranks.

Tunué’s work is also known to cater to young readers. In 2010, Tipitondi arrived, a series of comic books aimed at children and young adults. From 2011, Tunué even started to publish novels, unlike many publishing houses that started with novels and moved into comics.

Founded in 2010, Michele Foschini and Caterina Marietti’s BAO Publishing quickly dominated the Italian scene with a catalog that boasted over 350 titles after just a few years of operation. BAO’s international, multi-genre comics feature work from many countries, including the United States, Japan and Europe. Their publications range from children’s comics to genre comics and include adult graphic novels, superhero comics, recent Bonelli re-releases, deluxe editions, and experimental comic books.

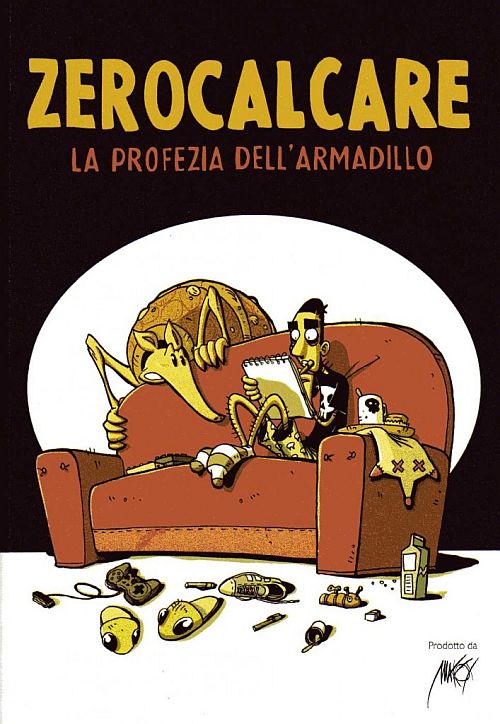

In 2011, BAO published the graphic novel La Profezia dell’armadillo (“The Armadillo Prophecy”), a collection of autobiographical stories held together by a unique fragmented narrative. The narrator is the protagonist of the book and he moves between contemporary satire, generational and nostalgic accounts, and ironic reflections on the daily life of twenty- to thirty-year-olds with a graphic style that embraces influences from underground comics, street art and manga. The first edition of La Profezia dell’armadillo, created by Zerocalcare and Makkox (Marco D’Ambrosio), was printed in a limited run of 500 and sold online. Five subsequent reprints brought the overall total to over 3,000 copies. Following this success, BAO released a color version of the book, now in its thirteenth print run with over 50,000 copies sold. BAO has also produced Zerocalcare’s other books, which, with the help of the author’s blog, have steadily climbed to the top of the charts, making the author one of the most important publishing phenomena of recent years.

Italian press (today) and the graphic novel

The comic book (or graphic novel) has long been a significant player in the Italian publishing market. The commercial success of the graphic novel has given publishers the leverage to shelve their comic books in the fiction sections of bookstores, far from the newsstands and specialized comic and art book stores. This hybrid form—which combines the textual complexity of a novel and the visual richness of a comic book—has attracted a new adult reading public.

Therefore, if the comic book market has grown so much and the stories themselves are so important and universal, why are they not discussed more? The Italian press and television networks have very little room for culture, but the quality is often high. If there’s so much hype surrounding comics and graphic novels, if there is such sustained interest from the reading public, if it is assumed that comics are not being marginalized but are marginalizing themselves (even if the successful marketing campaigns waged by many publishing houses in the last few years seem to suggest the opposite), why are they still not discussed more? Why are there not more broadcasts, news stories or articles? If the success of Zerocalcare manages to change this for the better, it will be a great victory, and all the ifs and buts at play here won’t weigh so heavily. If not, comics will once again recede, waiting for the next big name to re-emerge into the spotlight.

RETURN TO PART 1

From Graphic Novel: Storia e Teoria del Romanzo a Fumetti, by Andrea Tosti (Tunué, 2016). Translated from the original Italian by Storyline Creatives.

Header image from La Profezia dell’armadillo © Zerocalcare / BAO Publishing