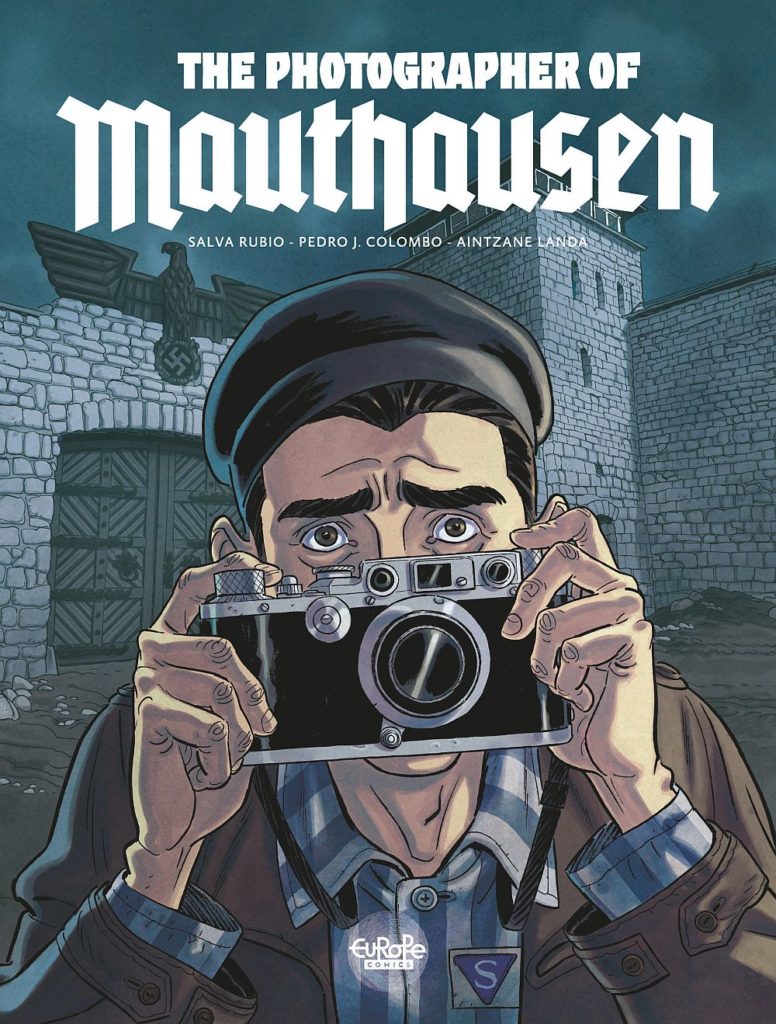

Our readers gained access to a particularly powerful tale recently, with the addition of The Photographer of Mauthausen to the Europe Comics catalog. The historical graphic novel is a dramatic retelling of events in the life of Francisco Boix, a Spanish press photographer and communist who fled to France at the beginning of World War II. There, things only got worse, as he found himself handed over by the French to the Nazis and sent to the Mauthausen concentration camp, where he would spend the war among thousands of Spaniards and other prisoners. More than half of them would lose their lives there. But through an odd turn of events, Boix found himself the confidant of an SS officer documenting prisoner deaths at the camp, and he decided to seize the opportunity, risking his life to steal the negatives of these perverse photos and let the world know about these atrocities being committed. Below, we delve into the historical and personal context of this remarkable and harrowing story.

Text by Salva Rubio, except where otherwise noted.

The deportation of Spanish loyalists to the Nazi labor camps

text by Rosa Toran

I’m writing these lines between two anniversaries that are highly significant to the history of the deportation of Spanish Republicans after the Spanish War. It has been 75 years since their exile from their homeland in 1939 and 70 years since the liberation of the Nazi concentration camps in 1945. Their story is quite exceptional. Not only had the women and men who experienced the horrors of the Nazi concentration camps already been imprisoned by the French in what were misleadingly called refugee camps, but after their liberation they were persecuted and silenced in their own country and thus condemned to permanent exile in the country where they had sought refuge.

The Spanish Republicans were among the first to take up arms to fight against fascism and they were among the last to leave the labor camps after the liberation of 1945. In other words, nine years of struggle and suffering. After the nationalist victory led by General Francisco Franco, the Republicans took refuge in France, expecting a quick return home. However, months and then years of uncertainty awaited them in a country where they thought they had found asylum, but where they were dependent on the policy decisions of successive governments that were embarrassed by their presence and suspicious of people they considered “undesirable reds.” Families were scattered all over France while men were obliged to join the French Army, the Foreign Legion, makeshift battalions, or, in most cases, the military units known as CTEs — Compagnies de travailleurs étrangers, or Foreign Worker Companies — in which they were forced to do menial labor in factories and farms, and to help build fortifications, making them into an army of shovels and pickaxes.

Members of the CTEs stationed near the northern and eastern borders of France were victims of the invasion by German troops in May of 1940. This invasion was followed by a period of dispersion, escapes, and attempts to cross into Switzerland, culminating in the arrest of some 10,000 men and women who were placed in POW camps alongside thousands of soldiers from all over Europe. The Republicans were abandoned by the collaborationist Vichy government, who didn’t recognize them as French soldiers, as well as by Spanish authorities under Franco who were then in negotiations with Hitler. Most of these detainees were sent to Mauthausen, a concentration camp located in annexed Austria, which was in need of slave labor for its construction projects.

Those who managed to escape this fate became stateless citizens trying to make it into free territory, and they spent the war in constant fear of arrest. Many of them joined the struggle against the enemy without hesitation — the same enemy that had forced them out of their country, only under a different guise.

The Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp

text by Ralf Lechner

Several days after the Third Reich annexed Austria in March 1938, the new authorities announced their intention to build a concentration camp there — a “privilege,” according to August Eigruber, the Gauleiter (regional leader) of Upper Austria. In expectation of a marked increase in prisoners, the SS, who managed the camps, planned to set up supplemental detention centers. At the same time, the SS leadership considered launching themselves in the manufacture of construction materials. The SS found in this plan a justification for the expansion of concentration camps as well as an exclusive source of manual labor. In April 1938, the SS established the Deutsche Erd- und Steinwerke GmbH (DESt) in order to manage the production of construction materials using forced labor from concentration camps. The SS then began to search for a location where they could build a concentration camp that would permit them to achieve their economic goals.

In the end, Mauthausen and Gusen were chosen because of their nearby granite quarries. The SS-run company would deliver construction materials for the prestigious buildings and monuments of the Third Reich thanks to the labor done at the quarries by prisoners of the concentration camps. On August 8, 1938, a first convoy of prisoners arrived at Mauthausen from Dachau. The prisoners were first enlisted in the construction of the camp itself. At the end of 1938 they were assigned to construct the second concentration camp in Gusen, a few miles from Mauthausen. For a time, Mauthausen was one of the only “grade III” camps in the Nazis’ concentration camp system. Within the “hierarchy” of concentration camps during the Third Reich, grade III meant that the conditions were harsher and the mortality rate even higher than elsewhere. Groups of prisoners were regularly sent to Mauthausen in order to be eliminated.

Photographic documentation

Francisco Boix, whose father was a photographer, demonstrated a talent for photography from a young age. At Mauthausen, he joined the Identification Service (or Erkennungsdienst), which was controlled by the Gestapo and the Politische Abteilung (Political Affairs Division).

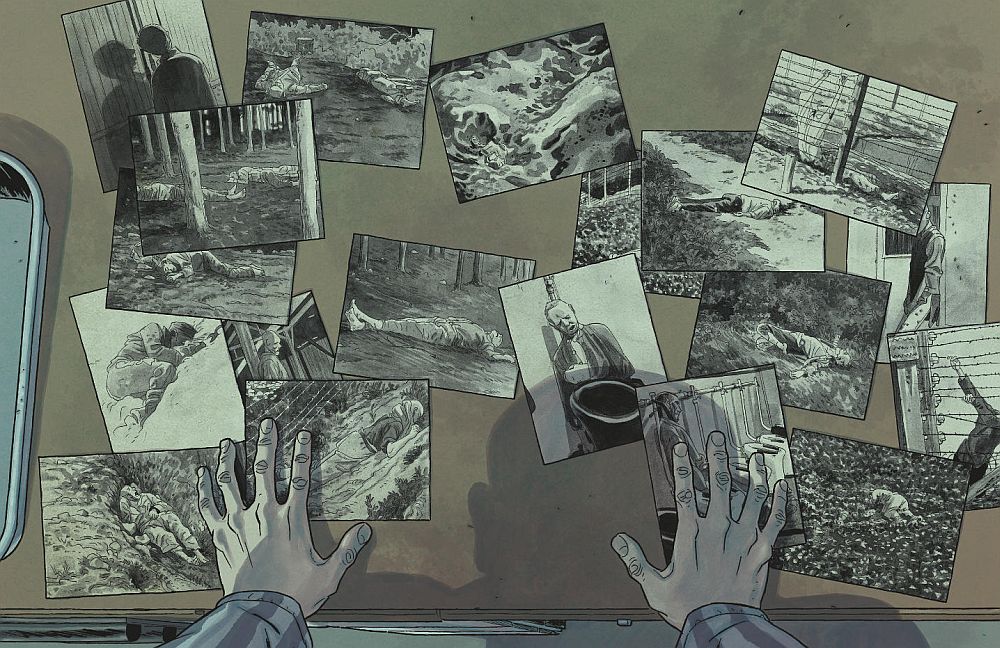

This department’s task was to document through photographic means the arrival and departure of the prisoners. It would also develop private photographs taken by soldiers and officers. Furthermore, the Identification Service took photographs of any prisoner who died under suspicious circumstances, such as murders that had been disguised as executions or suicides. Five prints were made of each photo: one stayed in the camp, while the others were sent to various archives. The first prisoner who decided to make a sixth print to be hidden was a Pole named Stefan Grabowski. The Spaniards followed in his footsteps.

The photographs that Boix didn’t expect to see showcased prisoners who appeared neither mistreated, sick, nor starving. These photographs were in fact staged images used to sell the prisoners’ services to local businesses, slave labor being a significant source income for the SS.

Ways to die at Mauthausen

Some people think, incorrectly, that Boix himself photographed murdered prisoners. In truth, the photos were taken by the SS. In particular, one recognizes the “signature” of Paul Ricken, who constantly looked for original viewpoints and compositions for his photographs, demonstrating Ricken’s strange personality and his fascination with death.

It is plausible to imagine — as we have done in our graphic novel — that Boix might have accompanied Ricken, carrying lights and equipment. At the same time, we took some liberties in showing Boix witnessing many kinds of death scenes when, as a matter of historical record, not all deaths were photographed. This was the case, most notably, for executions and deaths occurring in the infirmary (through poisoning or the injection of gasoline directly into the heart). Boix must have witnessed many “escape attempts” (as, for example, when a prisoner would be shot after being instructed to go pick strawberries or to toss his cap over the fence), “suicides” (as when a prisoner was given a choice between hanging himself or being beaten to death), and more.

Paul Ricken and the Identification Service of the Political Affairs Division at Mauthausen

text by Gregor Holzinger

By Paul Ricken’s own account, thanks to his technical know-how in the medium of photography, he started to work for the Identification Service of the Political Affairs Division — the “camp Gestapo” — in March 1940. It was in this role that he photographed prisoners as well as members of the SS and Nazi dignitaries who visited the camp. The Identification Service also collected snapshots of new extensions of the camp. He described his activities as follows: “My tasks at the Identification Service consisted among other things of filling out prisoner identification forms and photographing prisoners who died of unnatural causes or medical procedures and their results for the local SS doctor.”

In SS jargon, “unnatural causes” referred to accidents, suicides, or, in the majority of cases, what were referred to as “executions as the result of attempted escape,” such as in the cases mentioned above. While official executions were recorded in an “execution registry,” the Political Affairs Division additionally kept two other registries for these “unnatural deaths,” in which, as numerous eyewitnesses testified, a large number of causes of death were falsified in order to disguise massive, targeted executions and other acts of excessive violence. Each “unnatural death” was supposed to be subject to an extensive inquiry following a well-defined official procedure.

In reality, these “inquiries” never took place. Thus, after every so-called “execution as the result of attempted escape,” the Identification Service was informed and they would arrive on the scene to make a photographic record. Since the positions of the murdered prisoners bodies often did not correspond to an escape attempt, they were often “corrected” by the Identification Service. Numerous witnesses reported during Ricken’s trial that he would change the positions of bodies in order to make it look like they were trying to escape. He did the same thing in the case of “suicides”: Ricken would adjust the bodies of prisoners killed by kapos or by members of the SS in such a way that a conclusion of suicide could be supported.

The photographs taken by Ricken are remarkable in a number of ways: beyond their technical aspects such as exposure time and focus, Ricken’s photos seem to strive to be artistic. He was particularly attentive to composition and perspective, trying to make a small work of art out of every shot, as if he were immortalizing the beauty of nature and not the horror of murdered prisoners.

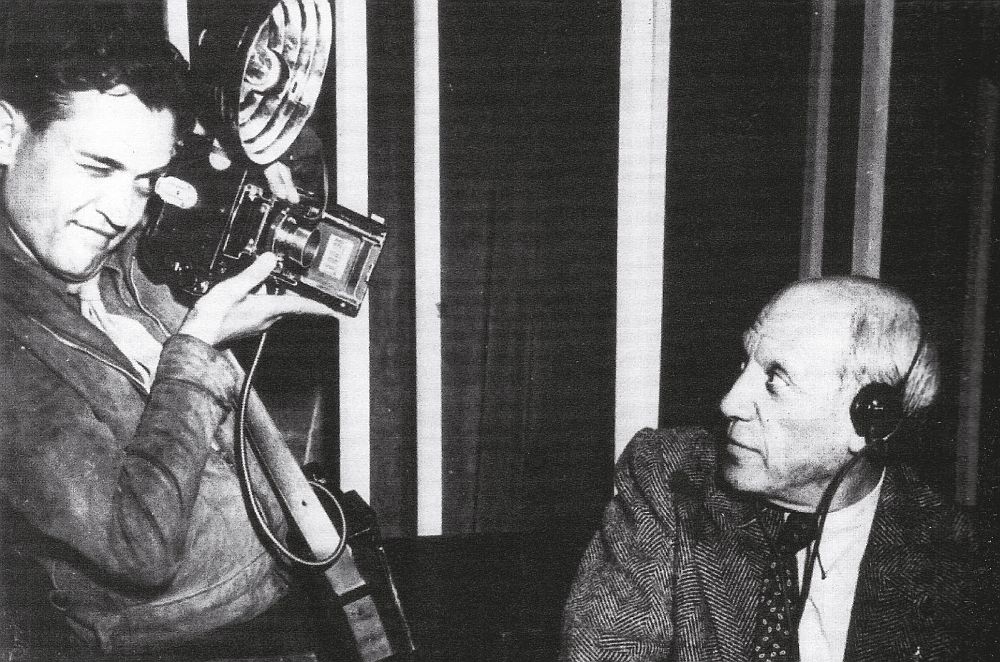

The liberation of the camp

In early 1944, the Germans started to sense defeat and the conditions for prisoners took a turn for the worse. Food rations were reduced, the soup was watered down, and the bread had more sawdust mixed in. The prisoners, fearing imminent execution or poisoning, started to make plans for a revolt in case of mass displacement or execution. Shortly thereafter, cannon blasts could be heard from the nearby front, and at that point, the SS decided to flee. It was also then that Boix got his hands on a Leica. All the photographs from that moment on were taken by Boix. Some of them have been reproduced in books about the Holocaust without ever crediting their author: the images shown include skeletal prisoners, women forced into prostitution, and the arrival of American journalists… Shortly thereafter, a squadron of American tanks discovered the camp by chance. Mauthausen was liberated by the 41st Cavalry Battalion, under the command of Sgt. Albert J. Kosiek, of the 11th Armored Division.

Epilogue

Francisco Boix spent the remainder of his short life in Paris, where he worked as a photographer documenting the exiled Spaniards’ fight to overthrow Franco from abroad. During this period, he even met Picasso. He passed away on July 7, 1951, just short of his thirty-first birthday, from an illness he probably contracted at the Mauthausen concentration camp.

Of the 9,328 Spaniards imprisoned in the camps, fifty-nine percent of them died there. Mauthausen alone took in 7,532 Spaniards, of whom 4,816 were murdered — 3,959 of that number, or sixty-five percent, at Gusen. Ninety percent of the deaths occurred between 1941 and 1942. After the liberation, many survivors died as a consequence of illnesses and poor medical treatment, while others — men, women, and children — suffered in exile. Only a handful of them are still alive today. They tell their stories, passing them down through the generations in an attempt to prevent history from repeating itself. In creating this graphic novel, we wished to honor their efforts and help keep their legacy alive.

Translated by Matt Madden.

Header image: The Photographer of Mauthausen © Rubio & Colombo / Le Lombard