In the quiet neighborhoods of Binghamton, New York, masses gather behind St. Patrick’s Parochial School around a roaring fire as parents and their children toss armfuls of comic books into the blaze amongst onlookers who watch with glee. It’s December 10, 1948, three years after World War II, and comics are under attack. The rally in Binghamton would spark similar fires around the country as crusaders for children’s morality waged war against America’s newest kind of books.

By the end of World War II, comic books had become a huge presence in American pop culture. Soldiers read comics, housewives read comics, and children of all ages read them as well. In 1946, Publishers Weekly reported an estimated 540 million comic books were printed that year. A few years later that figure had nearly doubled. Comic books were, without a doubt, big business, but this all-encompassing presence had its downsides.

As early as 1906, protests about early comic strips had sprung up across the country. These crusades, however, ended abruptly in 1911 as the United States entered World War I. Then in 1937, comic strips shifted focus from humor to action/adventure and the crusades began again. One study published in 1937 on comic strips appearing in Boston papers argued that children and adults who read comic strips regularly run the risk of lowering their artistic appreciation. Then, as the decade came to a close, criticism shifted from comic strips to the newest mass medium, comic books.

The first attack came from Sterling North, a literary critic for the Chicago Daily News, in an editorial on May 8, 1940, headlined “A National Disgrace.” As North wrote, “The antidote to ‘comic’ magazine poison can be found in any library or good bookstore. The parent who does not acquire that antidote for his child is guilty of criminal negligence.” It was reprinted by more than 40 newspapers and magazines. And a wave of similar editorials denouncing comic books filled papers nationwide, linking comic books to everything from straining eyes and nervous systems to lowering IQ.

One of the most significant aspects of North’s criticism was his identification of comic books as a form of juvenile literature. By categorizing comic books this way, North and other critics helped shape the public perception of comic books as being strictly for children. This would grant legitimacy to future critics like John Mason Brown, who made the hyperbolic statements on a 1948 radio broadcast that comic books were “the marijuana of the nursery” and “a threat to the future.”

The National Office of Decent Literature (NODL) was established in 1938, shortly after the Legion of Decency pressured the film industry into enforcing a rating system. The NODL’s concerns were with “morality” and comic books’ presence within American pop culture. Nationwide community decency campaigns took to the streets in teams armed with lists of objectionable comics and visited local newsstands, urging dealers to remove the “bad” comics.

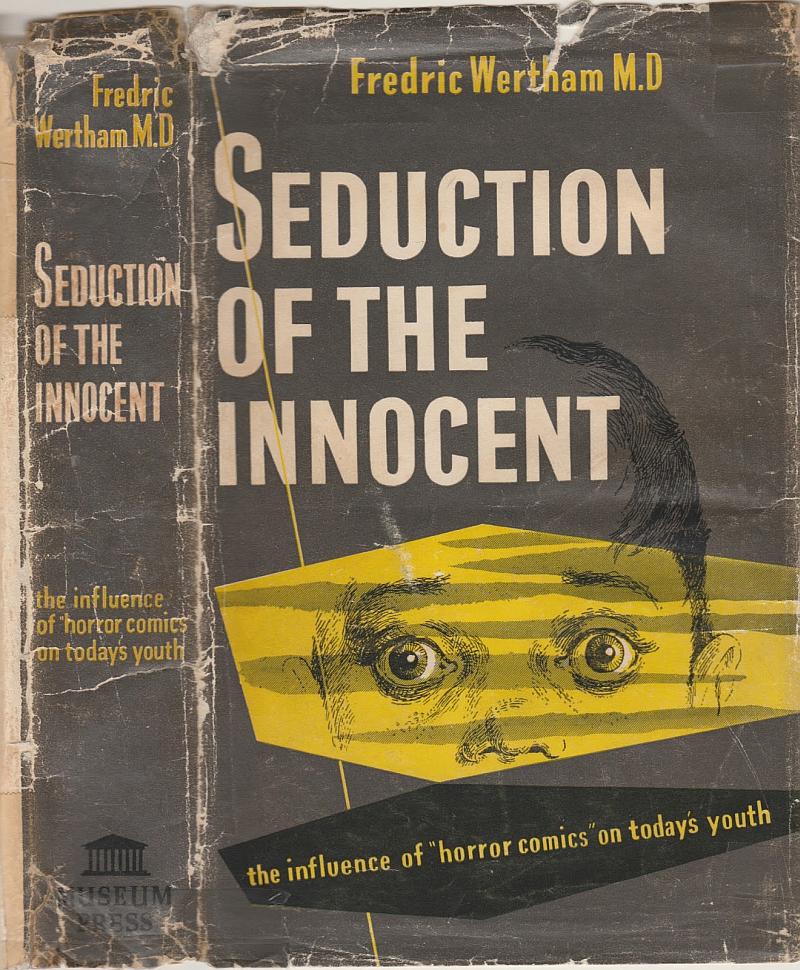

A major factor in the success of these campaigns against comic books was the linking of comic book reading to juvenile delinquency. And never was this link more burned into the American consciousness than when a psychiatrist named Fredric Wertham began his critique of comic books, beginning with articles, followed by a book, and onward all the way to a U.S. Congressional inquiry.

In 1946, Wertham helped open the Lafargue Clinic in the basement of St. Philip’s Church in Harlem, New York. It was here that, along with his associates, he first began a systematic study of the effects of comic books on children. The flaw in his study was that the subjects were all patients from his clinic. This eventually caused him to conclude that all juvenile delinquents read comic books, ergo comic books were the cause of juvenile delinquency.

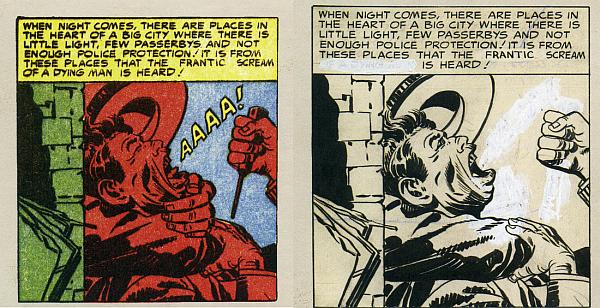

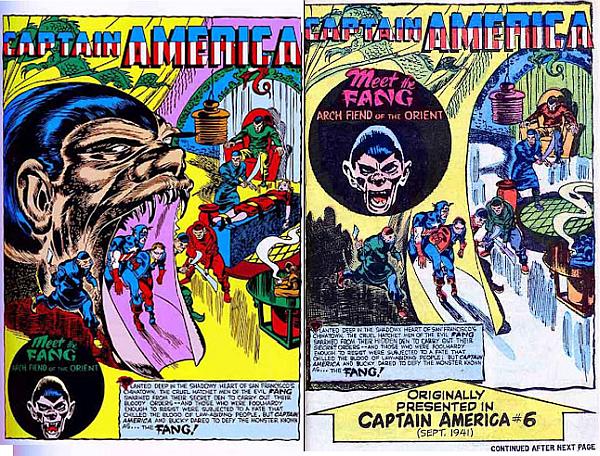

Wertham’s book Seduction of the Innocent was published in spring of 1954 and, among its reprintings of single panels pulled out of context from various comic books, and its sensationalist chapter titles like “The Devil’s Allies” and “I Want to Be a Sex Maniac!”, the book went on to conclude that Superman was a fascist, Wonder Woman was a lesbian, Batman and Robin were gay lovers, and comics were the cause of juvenile delinquency.

The success of Seduction of the Innocent and Wertham’s credentials would lead him to appear before the Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency, led by anti-crime crusader Estes Kefauver, in the comic book hearings of 1954 held in New York. It was here that Wertham would testify, “I think Hitler was a beginner compared to the comic book industry.”

All the negative press garnered by Seduction of the Innocent and the Senate hearings would eventually pressure the comic book publishers to institute the self-censoring organization known as the Comics Code Authority, which regulated what could be shown, said, and discussed within the pages of comic books.

Thus assuring that comics would be safe for kids—and just for kids—for the foreseeable future. As for the crusaders and critics concerned about the welfare of children, they moved on to the next juggernauts set to take hold of American pop culture: television, rock and roll, and, eventually, video games. Leaving the fires to burn out and allowing comics to slowly outgrow and move beyond the Code that had been forced upon them.

Text by Brian Canini. Originally published in The Columbus Scribbler. For more information, visit the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum website.

References:

- Comic Book Nation: The Transformation of Youth Culture in America, by Bradford W. Wright

- Fredric Wertham and the Critique of Mass Culture, by Bart Beaty

- Pulp Demons: International Dimensions of the Postwar Anti-Comics Campaign, edited by John A. Lent

- Seal of Approval: The History of the Comics Code, by Amy Kiste Nyberg

- Seduction of the Innocent, by Fredric Wertham

- History of Comics Censorship (web), Comic Book Legal Defense Fund

- The Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum – Ohio State University

Header image: Seduction of the Innocent © Wertham / Rinehart & Company