Comics in East Germany

From the outset, the political leadership of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) rejected comics and pulp novels as an imperialist form of reading that brutalized children and turned them against socialism. However, up until the construction of the internal German border, beginning with the building of the Berlin Wall, these kinds of books were smuggled into the GDR in large numbers from West Germany. In their fight against comic books, the authorities quickly realized that if they wanted to successfully ban their own children from reading the enticing stories of their political opponents, they would have to satisfy the population’s hunger for entertaining stories. It was therefore decided to create a comic book with clean content, which was consciously apolitical. This was in complete contrast to many other magazines, such as the youth journal ATZE, which was tightly aligned with the party ideologically.

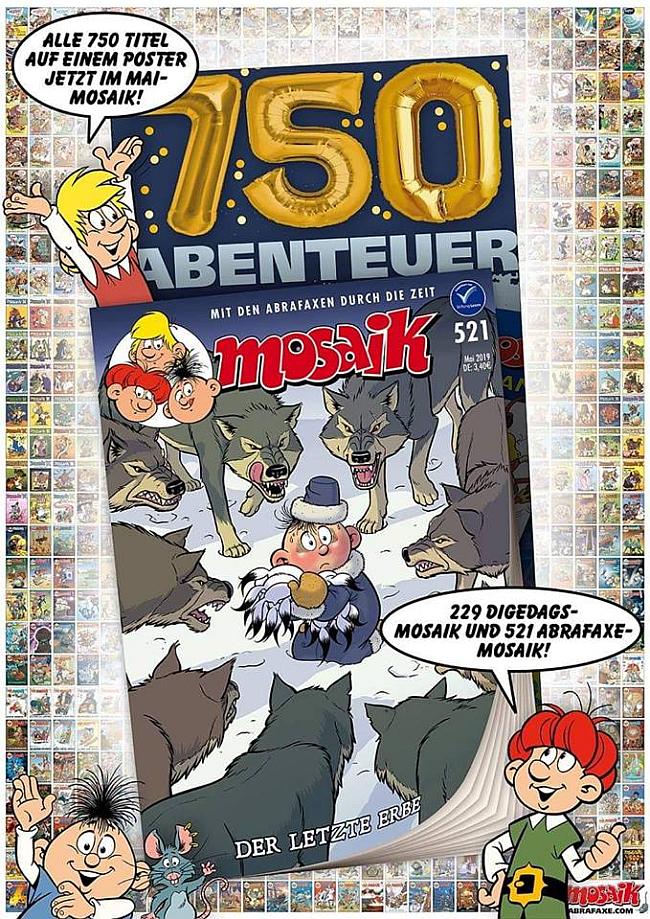

Already in December 1955 the first issue of MOSAIK magazine appeared, featuring the adventures of the three time-traveling goblins Dig, Dag, and Digedag. The characters were invented by Hannes Hegen (pen name of Johannes Hegenbarth), who worked with two assistants. In 1957, when the magazine moved to a monthly publication schedule, more employees were hired to fill out the team. In this way a complete comics studio was set up in the publishing house, in which writers, pencillers, inkers, and background artists as well as colorists jointly produced the magazine. Similar to Walt Disney or Rolf Kauka, Hegen’s greatest talent was not necessarily his own drawing or narrative creations, but the ability to put together a good team that successfully implemented his visions.

In 1975, Hegen, who worked independently (unusual for the GDR), terminated his publishing contract in order to negotiate more lucrative conditions for himself. Instead of giving in to his demands, the state-owned publishing house decided to continue without the artist. Since the title MOSAIK belonged to the publishing house under GDR law, a comic with new characters could be continued under the same magazine name. Hegen retained his copyrights and was allowed to reprint the Digedag comic books or create new stories outside MOSAIK. From then on, the magazine published the stories of three other time-traveling goblins who went about their adventures in the Middle Ages or ancient Rome under the names Abrax, Brabax, and Califax.

The changes did not diminish the magazine’s success. MOSAIK was published until the fall of the Wall with a circulation of up to 900,000 copies, which typically sold out within a few days. In the course of German unification, the magazine changed hands several times until it was continued by publishers Klaus D. Schleiter and Anne Hauser-Thiele. Thanks to a loyal readership, MOSAIK continues to buck the general trend of declining print runs and now sells more issues than the German Micky Maus. The magazine continues to be made by a salaried studio in the publishing house — now a villa in Westend (Berlin). In May 2019, the 750th issue of MOSAIK was published with the 521st installment of Abrax, Brabax, and Califax.

The 1970s

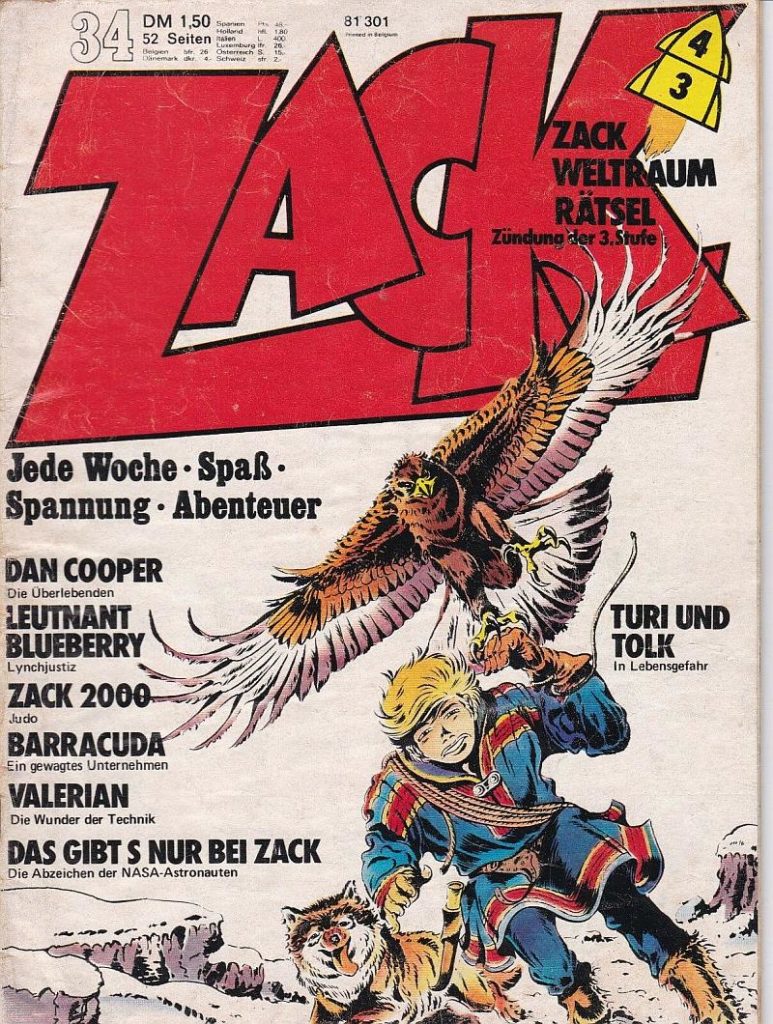

When the magazine ZACK introduced a new generation of readers to Belgian (Le Lombard) and French (Dargaud) adventure comics in 1972, Dieter Kalenbach and his series Turi & Tolk were the only German presence. However, ZACK played an important role for the German comics scene, because it was the first time that an entire generation of readers had understood that comics could be their own art form. Many new publishers and illustrators emerged from ZACK’s fans, who from then on took this author-driven approach as their model.

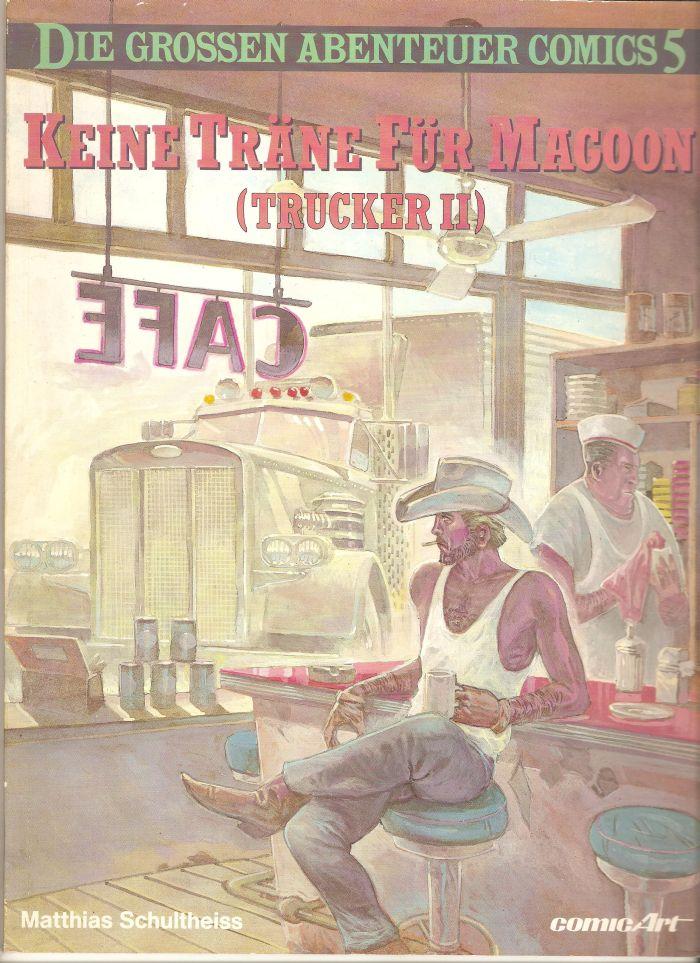

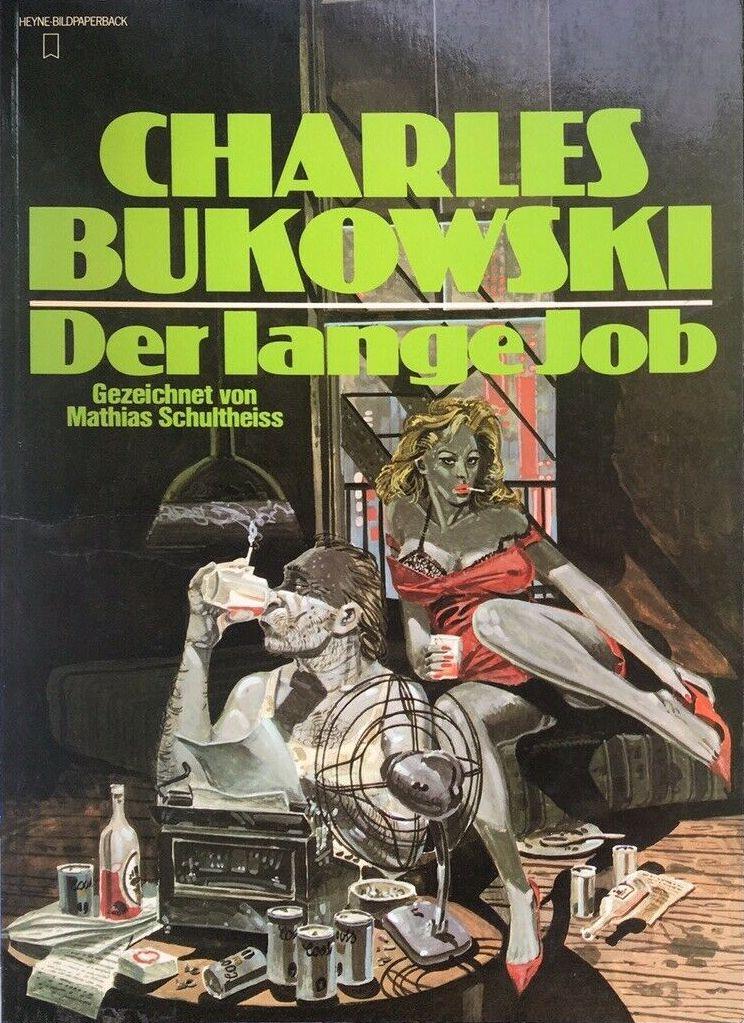

Unfortunately, many of them entered the market at a time when the circulation of comics was already beginning to decline throughout Europe. For example, a series like Trucker, created by Matthias Schultheiss, could no longer be published in ZACK because the magazine was discontinued in 1980. Thus Trucker was initially printed alongside contributions from other German artists in Comic-Reader, put out by the small publishing house Becker & Knigge, until the series was later published by Carlsen Verlag in color. Schultheiss became internationally famous by adapting short stories by Charles Bukowski, which found their way into the French comics magazine L’Écho des savanes. Germany was still the wrong place to make a living from elaborately drawn pages, so his series Bell’s Theorem and The Sharks of Lagos were first printed by French publishers and then in Germany and other European countries. Schultheiss also worked for Dark Horse and the Japanese publisher Kodansha, but retired from the comics business in the 1990s to earn his living writing TV screenplays.

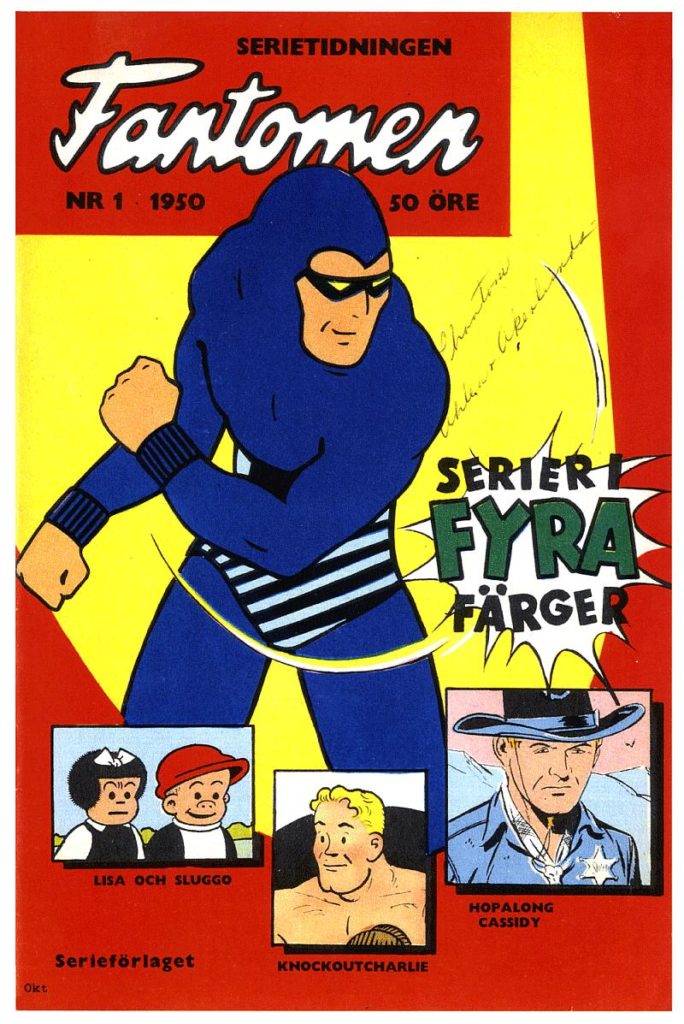

The poor working conditions for illustrators with a realistic style also drove Heiner Bade from Hamburg to Sweden, where he drew 32-page adventures of Lee Falk’s The Phantom for the magazine FANTOMEN from 1974 onward. Even after he returned to Hamburg in the mid-1980s, Bade remained faithful to the figure and still draws it today. In particular, his stories, which are set in a historical context, have artistic qualities that German readers are used to finding only in Franco-Belgian-style bandes dessinées. Claus D. Scholz from Wolfsburg took a path similar to Bade’s, but he emigrated to Antwerp, where he first worked for Frank Sels and his team on the series Silberpfeil for Bastei Verlag. Later he drew the Belgian classic The Red Knight until he retired.

Andreas (pen name of Andreas Martens), whose enthusiasm for Franco-Belgian comic art led him to the Saint-Luc Institute in Brussels, had a similar fate. At the Académie de Saint-Gilles he attended comics courses with Eddy Paape, whom he soon assisted with several series. This collaboration opened the way for him in magazines such as À suivre, Le Journal de Tintin, and Métal Hurlant. Andreas still lives and works in France and has created series like Cromwell Stone, Cyrrus, Capricorne, Arq, and Rork (Europe Comics in English).

From the 1980s to the present day

The magazines Schwermetall (Heavy Metal) and U-Comix, aimed at an adult audience, mainly published stories from France and the USA, but also frequently offered the work of German artists. Inspired by ZACK, Schwermetall, and American underground comics, fan creations developed from the early 1980s onward, quickly becoming more professional. While magazines like Algier tended toward ZACK, Menschenblut oriented itself towards artists like Richard Corben. Comic books like Hinz und Kunz, on the other hand, were modeled on the work of Gilbert Shelton and Robert Crumb. What they all had in common was that they offered their contributors great artistic freedom beyond the mainstream, but they could hardly pay them. Therefore, many artists turned to other professions that enabled them to survive.

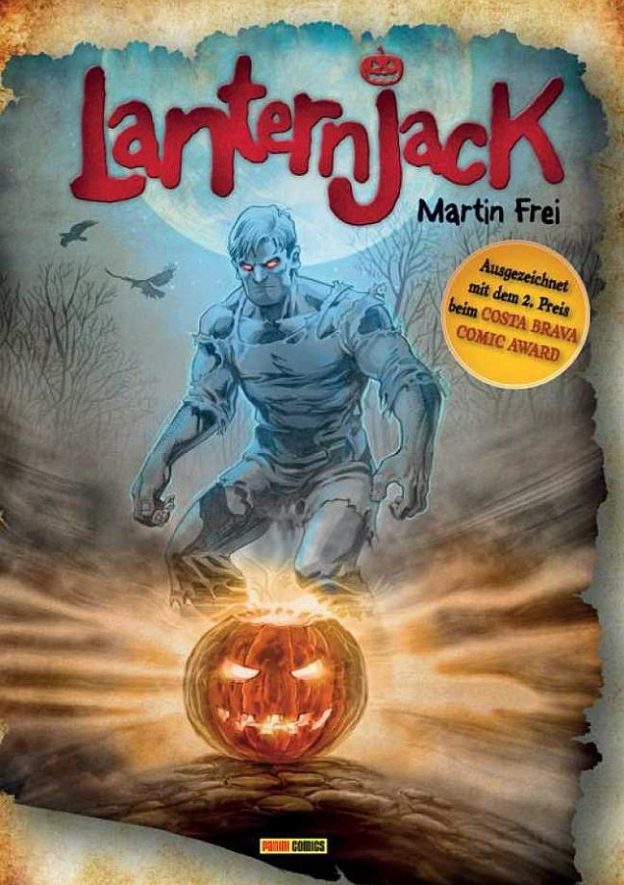

One of the few who are still active today from this time is Martin Frei from Stuttgart, who has already drawn many albums in the Franco-Belgian style and won 2nd place at the Spanish International Costa Brava Comic Awards with his one-shot Lantern Jack. Frei achieved his greatest successes with the crime series Kommissar Eisele and also often draws in a comedic style, including for the German edition of MAD Magazine. Geier (pen name of Jürgen Speh), who illustrates books by the successful author Rebecca Gablé, now continues Hansrudi Wäscher’s sci-fi series Nick the Spaceman and draws for children’s magazines of the Blue Ocean publishing house.

In the course of the 1990s, publishers such as Carlsen and Ehapa made great efforts to establish German artists based on the Franco-Belgian model, but only a few of them found continuous success. Those left are mainly Isabel Kreitz and Reinhard Kleist, who from the beginning anticipated what would later be known as the graphic novel. Isabel Kreitz quickly aroused the interest of Carlsen Verlag with her first albums about the S-Bahn surfer Ralf, at the small publishing house Zwerchfell, and it’s now hard to imagine the German comics world without her. Although she is highly esteemed for her own material, she has also had great success with adaptations of famous novels. Reinhard Kleist has meanwhile specialized in biographies of such figures as Johnny Cash, Elvis, Fidel Castro, and Nick Cave, among others.

Among the most important German-speaking artists is also the Austrian Ulli Lust, who has lived and worked in Berlin since 1995. Initially known for her reports in the form of comics, she had her international breakthrough with the autobiographical graphic novel Today is the Last Day of the Rest of Your Life (avant-verlag; Fantagraphics in English), for which she received awards in Germany, France, and the USA.

Otherwise, comics from the era mainly included artists with a cartoon-like style, such as Ralf König and Walter Moers, who achieved great success with their work, leading to numerous translations in other languages. Ralf König still captivates today with his subtle observations of the gay scene, and has also published parodies like The Killer Condom.

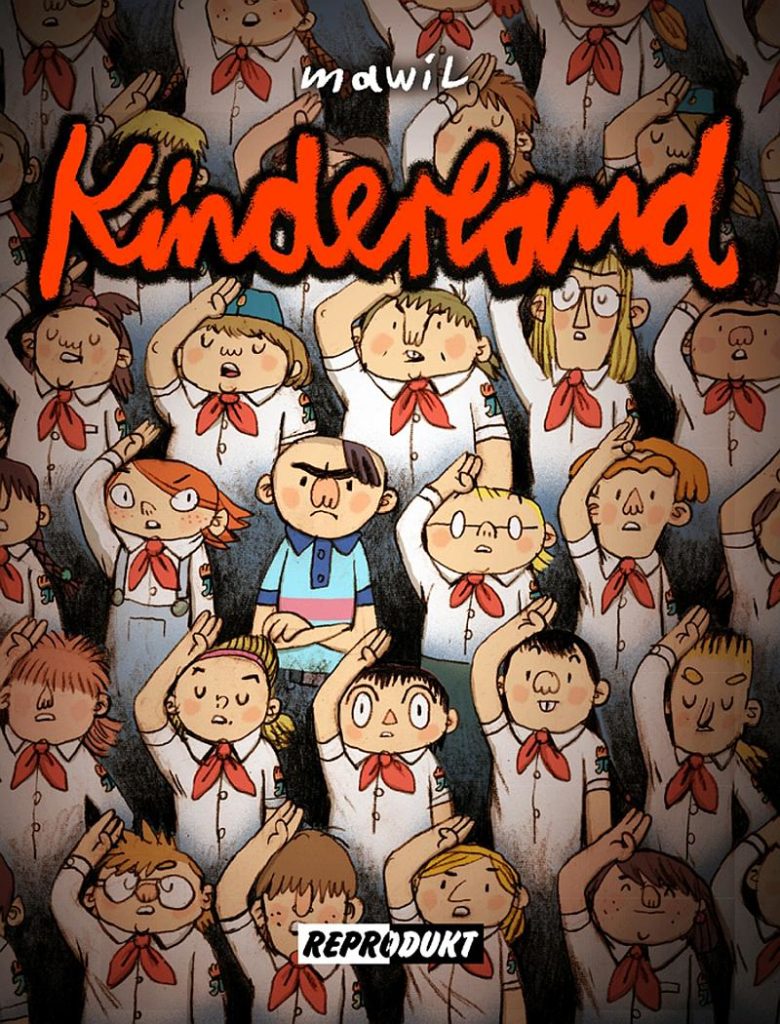

The idea that it is easier for German artists to make a living from their work when they master a quicker, comedic style is also supported by the work of younger artists such as Mawil (pen name of Markus Witzel), born in 1976, who broke through on the international scene with his graphic novel Kinderland – A Childhood in East Berlin (Reprodukt). Born in the same year, but in West Germany, Felix Görmann (alias Flix) is a multitalented artist with a tendency toward subtle relationship dramas, told through an autobiographical lens. It’s no coincidence that Mawil and Flix, who stand out for their overall body of work, were chosen to reinterpret the classic Belgian heroes Lucky Luke and Spirou in their own personal styles (see Lucky Luke Saddles Up, and Spirou in Berlin).

But in 2017, artist Arne Jysch also showed that realistic stories from German artists still hold some appeal to German audiences with his adaptation of Der nasse Fisch (“The Wet Fish”), a historical thriller by Volker Kutscher, which also served as a model for the German television series Babylon Berlin. Jysch, who has studied animation and mainly draws storyboards for movies, has also mastered a fast style. The smaller graphic novel format along with new scanning techniques help him to save time as well. These aspects also benefit young artists who have come to graphic novels via manga. One example is Kristina Gehrmann’s trilogy Eisland (Iceland), which deals with the failure of the Franklin expedition in its search for the Northwest Passage. Her work has already been reprinted several times. Then there are artists like Oliva Vieweg, who always like to surprise with new story approaches. Her three-hundred-page zombie apocalypse Endzeit has even been adapted into a film, with an all-female crew.

In addition, there is a new generation of illustrators who have dedicated themselves with passion to realistic comics, and who make use of digital technology to attain a continuous output. The comics adaptations of bestselling author Kai Meyer, which artist Ralf Schlüter and his team have been successfully implementing for years, also warrant mention here. Or the dystopia Gung Ho by Benjamin von Eckartsberg and Thomas von Kummant, published simultaneously in German and French. One of the most productive artists, however, is Ingo Römling, who has drawn numerous episodes for Star Wars Rebels and Star Wars Resistance, in addition to the Malcolm Max series. He is currently working on a new series for Dargaud.

However, the most successful German release in recent years was the elaborate adaptation of The City of Dreaming Books by Florian Biege, which was financed by the successful novelist Walter Moers out of his own pocket. Although the two volumes were put out by a publishing house that does not otherwise print comics, the two-part graphic novel led the sales charts for almost two years.

In addition to the successes among recent graphic novels, there are small press magazines that publish mainly German artists, primarily out of love for the medium. Examples are the horror, science-fiction, and fantasy comic books of WEISSBLECH Comics, which are modeled on the American EC Comics of the 1950s, or the reboot of U-Comix, which gives many young artists the opportunity to publish short stories without commercial constraints. In this way, the German comics scene remains unpredictable and creative like never before.

Text by Bernd Frenz (www.berndfrenz.de). Beginning as a comics journalist in 1990 for the magazine PANEL (winner of the Prix de la bande dessinée alternative, or Alternative Comics Prize, in 1999), Frenz has since worked for all major German comics journals, including Alfonz, Comic Report, Comixene, Hit Comics, and Reddition.

Header image: Rork © Andreas / Le Lombard