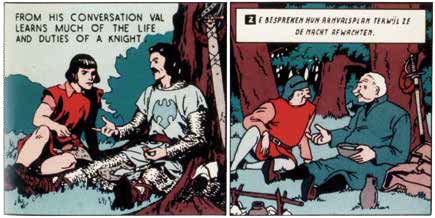

These borrowings, however, seem very modest compared to the organized plunder committed by Willy Vandersteen, one of the most famous Flemish cartoonists, over a period of no less than nine years. Between 1945 and 1954, he shamelessly plagiarized great American series such as Tarzan, Flash Gordon, and, above all, Prince Valiant. The reader will notice this “influence” in series such as Lancelot (1945), Het rode masker (The Red Mask , 1946), Tussen water en vuur (Between Water and Fire, 1948), Tijil Uilenspieger (Till Eulenspiegel, 1951) and even some Willy and Wanda stories, including Het geheim van de gladiatoren (The Secret of the Gladiators, 1953), De schat van Beersel (Beersel’s Treasure, 1952) and Lambiorix (1949). Finally, note that another of his storylines bore striking similarities to H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds. Möhlmann’s frame-to-frame comparisons of Vanderseen and Foster’s plates didn’t leave much room for doubt. When it hit the media, this revelation came as a bombshell. “Calling it borrowing is a euphemism for what Vandersteen did. Pilfer would be more appropriate,” wrote the Dutch daily newspaper Het Parool.

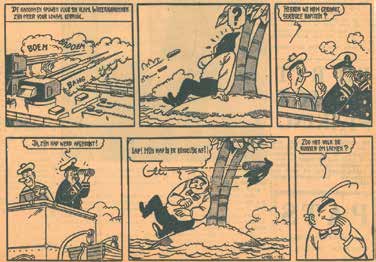

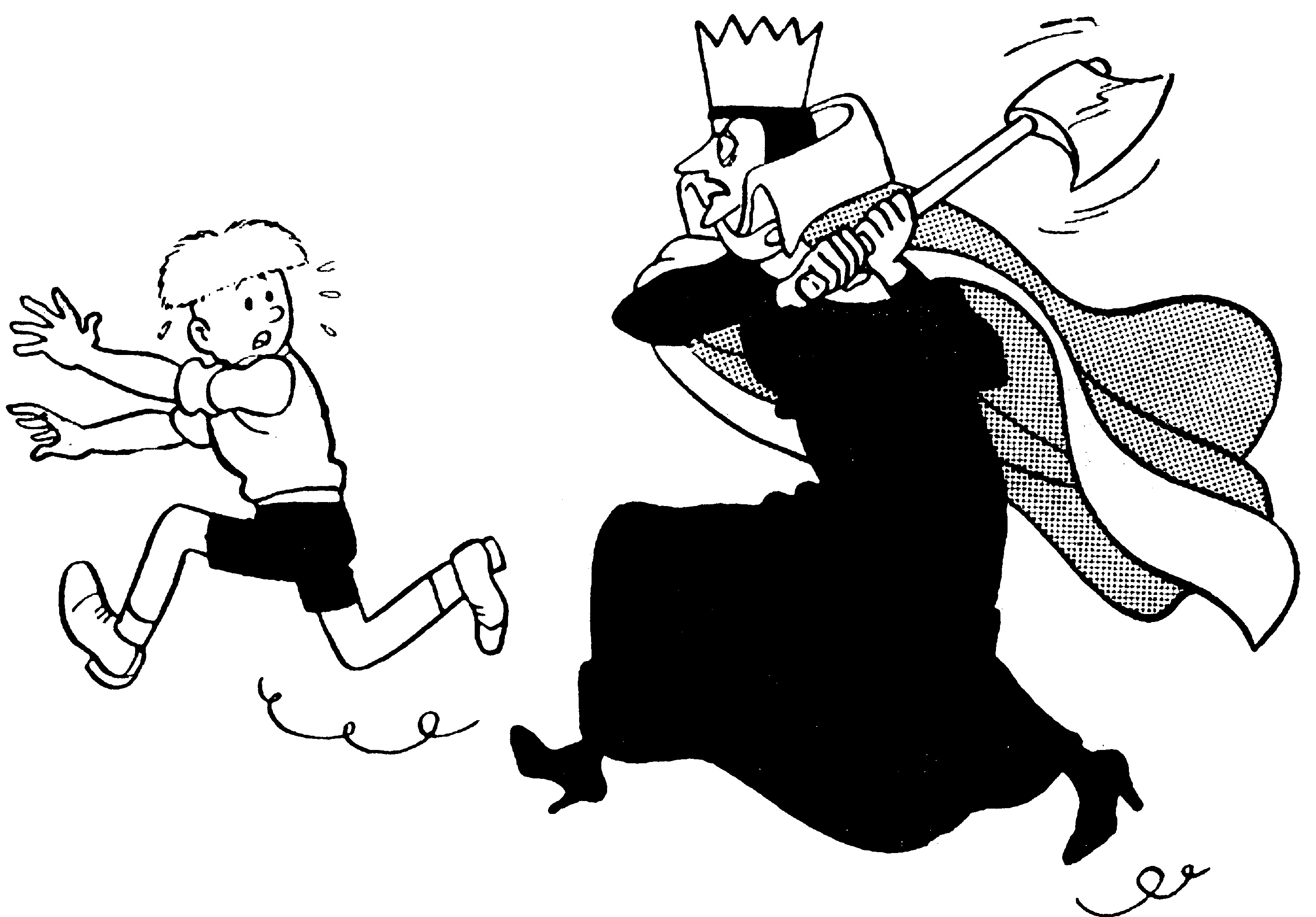

A few examples: though Vandersteen’s Ridder Gloriant (Sir Gloriant) was a mere 31 pages long, the Flemish master managed to commit no less than 36 obvious acts of plagiarism, 8 of which appear in a single episode. And these were plagiarisms concerning only the artwork! Indeed, the story of the brave Sir Gloriant strongly resembles that of Prince Valiant. In his hazardous quest, Valiant is lost in the marshes where he rescues a wild man, whose mother happens to be Gorrit the witch. As a token of her gratitude, the witch foretells a life of glory and danger for the knight. As for Vadersteen’s Gloriant, again, the hero is a knight wandering in the swamps where he helps a wildling out of a bad situation. By way of thanks, the wildling’s mother, a witch named Horrit, assures him his life will be filled with perils and deeds of valor. The similarities are uncanny. And even the various twists of the stories look a lot like the adventures of Foster’s prince. In Het verzonken rijk (The Sunken Kingdom), a science-fiction tale invoking the legend of Atlantis, Vandersteen mixed sources and borrowed from not only from Alex Raymond’s works, but also from Tarzan and Prince Valiant. Finally, Tussen water en vuur (Between Fire and Water), a 24-page-long prehistoric tale, presented an incredible 56 instances of plagiarism. In one of the episodes, every single page was copied by Vandersteen. Moreover, many ideas, such as the technique used to forge a spear, or how to defeat an enemy, were identical to those in scenes found in Prince Valiant. The most striking example was a scene in which Valiant attacked barbarians with a singing sword on a humpback bridge. When the “black book” came out, the scene was widely used by the media to show the extent to which Vandersteen had copied this act of bravery. The result? According to Möhlmann, a “rough” approximation “without soul or inspiration.”

At first, Vandersteen played down the accusations. “Oh! Plagiarism, plagiarism… such a big word,” he said. Denial was initially enough considering the limited circulation of the first edition of Möhlmann’s book. But when the media picked up on the story, this most famous of Flemish authors had to respond. He admitted that he “may have let himself be overly guided by his American peers,” adding that “the infinite admiration” he held for Hal Foster must have played a part. On September 26, 1981, during an interview with the Dutch weekly magazine Vrij Nederland, he confided: “Listen… I think this so-called black book talking about me is in itself a precious contribution to the history of the comic strip. I have one caveat: it lacks completeness. It could have showed many more examples of what the author calls plagiarism, from me, or many other cartoonists of the time. Nowadays, budding cartoonists have it easier, they can learn the trade in schools. We had to learn as we went along, without any training. So it was normal to use a giant like Hal Foster as a reference. It was the same for [Gustave] Doré whose works had long been in the public domain. To be honest: I couldn’t possibly have done better. I’m not proud of it, but we didn’t know what we were doing. It’s all true and I agree with the contents of the book, even though, personally, I feel he could have shown more leniency. You can call me a plagiarist, but actually I was only a fool among many others.”

It came as a great surprise that in April 2015 more accusations of plagiarism befell Studio Vandersteen, 34 years after the publication of the “black book,” which was still a sore spot. Vandersteen found himself yet again sitting in the defendant’s seat. Dutchman Leo Kupers released 44 very eloquent examples on the Flemish (comics) news site Stripspeciaalzaak. Scenes from an album of De Rode Ridder (The Red Knight) and 8 others from Bessy, published between 1968 and 1974, presented a lot of similarities with frames taken from 7 of the first 10 albums of the classic European western: Blueberry, by French comic strip artist Jean Giraud and Belgian writer Jean-Michel Charlier. A month later, another 17 illustrations from the pages of Bessy presented disconcerting similarities with scenes from Matho Tanga, a series penned by Dutch master Hans Kresse. “While we can consider some of these illustrations ‘deeply inspired by,’ others look like outright plagiarisms,” says Kupers, who hammered another nail into the coffin by adding that the discovery did not require exhaustive research. Fingers mainly pointed to the studio’s two assistants, Karel Verschuere and Karel Bideloo. The “black book” had already indicated their involvement back in 1981: Biddeloo due to the fact that he had copied a monster created by US writer Frank Frazetta, and used it in his own Rode Ridder series in 1979, and Verschuere because, among other things, he had included a drawing that looked exactly like the cover of the Tintin album The Broken Ear (L’Oreille Cassée) in his story Miquel (1972).

Marc Sleen, Willy Vandersteen’s editor-in-chief

The release of the Dutch magazine Ons Volkske was a major step. In December 1944, the company De Gids breathed new life into the old family magazine Ons Volk (Our People). When it came to illustrations, they quickly called on another great Flemish cartoonist: Marc Sleen. However, Sleen did not just provide illustrations, he also got the publisher’s approval to launch a new youth supplement. Ons Volkske (Our Small World) was first published in the fall of 1945. Its ten pages contained comic strips and children’s tales. Sales figures soon skyrocketed. Following this success, the umbilical cord was cut and Ons Volkske became an independent weekly magazine with Marc Sleen at the helm as both editor and illustrator. Sleen filled almost all the pages with his own creations. When he was asked, however, to publish a captivating historic tale, with preferably realistic artwork, Marc Sleen hired Willy Vandersteen. Four years earlier, under the pseudonym Wil, Vandersteen had begun his career with Wonderland. For Ons Volkske, the artist from Antwerp created his Sir Gloriant (previously discussed in “We didn’t know what we were doing”). At the time, Vandersteen was obsessed with the 16th century, an era from which he drew inspiration for decades. He went on to write The Red Mask, The Spanish Ghost and Thyl Ulenspiegel, all tales based on real events of that era.

Vandersteen was certainly the most renowned and best-selling Flemish cartoonist. His undeniable influence left a permanent mark on the world of Flemish comics. Pretty much everything he touched turned to gold. His brush produced the following works: Suske en Wiske (Willy and Wanda), De familie Snoek (The Snoek Family), De Rode Ridder (The Red Knight), Pats, Bessy, De Geuzen (The Beggars). As for Marc Sleen, he did not stay idle, launching Piet Fluwijn en Bolleke (The Adventures of a Father and His Son), Stropke en Flopke, and the bald-headed Nero, a Belgian publishing sensation since 1947.

In Nero, even though Marc Sleen described his main hero as apolitical, the cartoonist delivered a harsh critique of society. Local and foreign politics were often subject to severe thrashings. But, much like Hergé, who was influenced by his editor-in-chief in Tintin and the Soviets, Marc Sleen was asked by his publisher to pick a certain color and stick to it. “When I started, I was working freelance,” Sleen recalled. “And there were few ways to get gigs. Everything was either red or blue, socialists and communists had to be banished. I was a beginner and had little ambition. I was doing as I was told.” According to Sleen, this influence persisted until 1962. “But it’s totally normal to evolve between the ages of 20 and 80, don’t you think? When I was young, we were told Germany was the devil. But the Germans I met later in life were friendly and handsome young people. And I wondered: so these are the monsters who rape our women? It doesn’t mean we should become pro-German or Nazi. Some of my friends actually did. They even went to fight the Bolsheviks. I don’t know who managed to convince them that these ‘barbarians’ had to be fought, but it is certain that German propaganda was terribly effective.”

Daily comics

Belgian comic strips published in French and their counterparts in Flemish evolved in an increasingly independent manner. In the French-speaking part of Belgium, daily and weekly newspapers often had a full page dedicated to comic strips. In Flanders, the readers often favored daily strips. Series like Nero, Willy and Wanda, Kari Lente or Piet Pienter en Bert Bibber were published daily in the major newspapers, one or two comics per issue, ending on a more or less successful cliffhanger designed to hold the reader’s interest in the series and have him rush to the newsagent the next day and buy the latest installment.

In 2012, looking back on those heroic times, Marc Sleen remembered: “Nowadays, a comic strip artist would have to pay to see his work in the newspaper. Back then, it was the opposite. Comic strips artists like me, we captured and kept the readers. Of course, there was no TV, it was easier… But, at the time, I drew two comics a day ending in suspense, with a cliffhanger, so that people would wonder what would happen next. It was very difficult, but thanks to my imagination, I managed. Day after day, we tried to provoke the public’s curiosity. In those days, comic strips were very popular. And so was Nero…”

The American example was proof that the model could engage readers. But, as in the US, it led to a war between Flemish newspapers. The apple of discord: Marc Sleen. Or more precisely Nero, his most popular anti-hero. Sleen himself was unaware of the pull of his creation until he left Het Volk and took the comic strip with him, joining Het Volk’s competitor De Standaard. “All of a sudden, Het Folk lost almost 30,000 readers! Only then did I realize the magnitude of it. Volk’s managing director and his team came up to my place and begged me to come back. They even sued me for the ownership of Nero. My place was raided, I went to court… Volk claimed I owed them one million Belgian francs, because they figured that, after publishing Nero for all those years, they had acquired some sort of moral right over him.”

During the trial, Nero was banned from publication for a period of three months. “Still, he appeared in the pages of the Standaard anyway,” Sleen remembered. “But for legal issues, I had to cover him with a cap and make the other characters unrecognizable.” Sleen himself didn’t directly participate in the creation of these episodes, drawn by Willy Vandersteen and his assistants, and written by Gaston Durnez. “It wasn’t my Nero anymore,” Sleen said.

The great rivalry between the two Flemish masters of the comic strip was evident. Things became worse when Sleen officially joined the Standaard newspaper, where Willy Vandersteen had been calling the shots for years and enjoyed a kind of monopoly. “We were good friends, as long as we didn’t have to work together,” Sleen replied to those criticizing the unavoidable showdown that was bound to follow. “Two stars under the same roof? Vandersteen never managed to come to terms with that. He never wanted me to get the same circulation as he did. He said so himself, in this publishing house, in front of the board: I was allowed to come to the Standaard, but there was no way the circulation numbers for Nero could exceed his series’ circulation of 100,000 copies. I got a 70,000-copy print run. At the time, we were the only two major writers in the world of Flemish comic strips. Vandersteen and I were the stars, Jef Nys came third. His Jommeke series was in fact a product for younger readers: boys of eight, nine or ten years of age. Nero, which often dealt with politics, was aimed at a more adult audience.”

It was a critique Jef Nys had been hearing for a long time. “When they spoke of the Great Flemish Four, they mentioned Marc Sleen, Willy Vandersteen, Bob De Moor and then—only because they had to—Jef Nys. I’ve always been looked down upon because I wrote children’s comics. They think it’s easier, which is utterly false, but you learn to live with it. Initially, though, Jommeke was not developed for kids alone,” added Nys, many years later. The first stories, published in 1955, had a much more adult tone. “I hadn’t decided yet who the series would be talking to. At that time, I was going for an audience aged 7 to 77, really. But, one fine day, someone told me: ‘Jef, you’ll get in trouble with Marc Sleen’,” who at the time was still working for the Volk. “To avoid stepping on his toes, I figured that aiming Jommeke at children wasn’t such a bad idea.” Nys even believed Sleen was annoyed at the lasting success of Jommeke, which has remained a best-seller among Flemish comic strips for decades. “Sleen did good work at Volk, despite the fact he was always running late because he had too much on his plate. But I think he left partly because he wasn’t alone in the newspaper anymore.”

A lack of Flemish schools

In the years following the war, there remained a lack of common ground between Walloon and Flemish comic strips. Both kept on evolving on parallel courses, taking on diverging aspects and subject matter. It’s a little strange because, at the same time, interest in comic strips was on the rise in Flanders. Magazines that were wholly dedicated to comics were launched (not just supplements for the dailies) and the translations of Tintin and Spirou were a great success. However, though the Brussels school found success and became renown in Flanders, the Flemish school had a hard time crossing the borders of its native region. As such, can we speak of a “Flemish school”? In terms of style, not really. The Walloon authors would actually inspire their Flemish counterparts, once the American influence had been eliminated. While Hergé’s influence is evident in Ric et Pom, and Berk and Bob Mau studied Franquin, we would be hard pressed to find an example in the other direction. One country, but with two well-delineated comics regions that would independently follow their own separate roads on either side of the linguistic border.

From La Belgique dessinée by Geert De Weyer

Translated from the French by Storyline Creatives