As an only child, Ralph Meyer occupied his time with reading and drawing. His mother wanted an artist even before he was born, so the moment young Meyer started showing signs of an artistic temperament, she did everything she could to cultivate his passion, sending him off to workshops at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris, where he tried out all sorts of different mediums, from painting to etching.

As an only child, Ralph Meyer occupied his time with reading and drawing. His mother wanted an artist even before he was born, so the moment young Meyer started showing signs of an artistic temperament, she did everything she could to cultivate his passion, sending him off to workshops at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Paris, where he tried out all sorts of different mediums, from painting to etching.

He also devoured comic books, anything from the slapstick comedy of Gaston to the Blake and Mortimer investigations. The discovery that you could tell stories through pairing drawings and text came as quite the revelation for Meyer, and he knew from a very young age that comic books would be his calling.

Around about the time he was supposed to start making decisions about his future, Ralph was struck by a magazine article tantalizingly entitled How to become a comic book artist. The article included a list of art schools with a ‘comics’ department, among which was the much-extolled St. Luc institution, in Liège. But the deciding factor for Meyer was Liège’s reputation as a ‘party town’… Belgian beer and comic books – how could he possibly resist?! So that was that, at 20, he packed his bags and made his way over the border to Belgium to follow his childhood dream.

Although he already had a solid base in illustration before enrolling in St. Luc, he nonetheless found it a humbling experience. One of his most valued lessons from his days at the academy was that the most interesting illustration is not necessarily the most beautiful, or the most spectacular, but the one that demonstrates a certain degree of originality.

Meyer is known for his scrupulous realism. His great artistic idol is Jean Giraud, mostly due to his creative philosophy that an artist does not have to confine themselves to one particular style or genre throughout their whole career. Indeed, Meyer seeks to create a ‘bespoke’ graphic style for every project, tailored to fit the particularities of the script. Imposing certain constraints means that he is pushed out of his comfort zone, forced to adapt himself accordingly. In so doing, he remains open to experimentation and avoids being locked into any one graphic category. “Drawing is a game,” he says, “you have to have fun with it.”

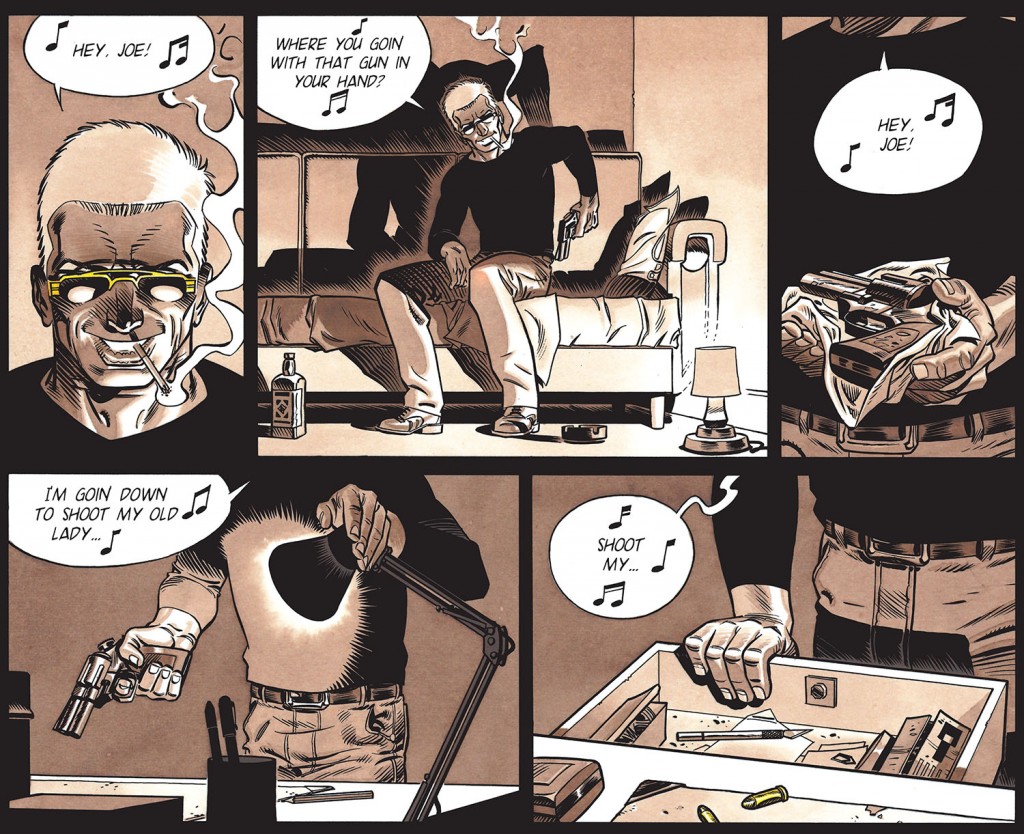

Despite his obvious talent, Meyer’s initial attempts to approach various publishing houses did not meet with much success. It wasn’t until he presented his work to writer Philippe Tome that Meyer landed his first big project: the Berceuse Assassine trilogy (1997 Dargaud, 2016 Europe Comics, Lethal Lullaby), a dark psychological thriller, set apart by Meyer’s stunning artwork, distinguishable by his attention to detail and remarkable use of light and shadow. Meyer was delighted with the success of the series which, thanks to its originality, remains to this day any bookshop’s go-to in the comic book thriller genre.

Meanwhile, he set about founding the Parfois j’ai dur workshop with a few other European comic book artists, creating an umbrella under which those solitary artistic souls could unite. The workshop gave this diverse group of young artists four carefree but highly educative years, during which they divided their time and energy between the drawing board and… the bar down the street.

From there on in, he’s been producing hit series after hit series. After Berceuse Assassine came Des Lendemains sans nuages, (2001 Le Lombard) which he co-illustrated with Bruno Gazzotti with Fabien Vehlmann on script. Next up, still with Vehlmann, he started the sci-fi series Ian,(2003 Dargaud Benelux) which narrates the adventures of a being of artificial intelligence, covered with human skin and nerves.

2008 marked the beginning of a fruitful collaboration with Xavier Dorison. Meyer describes their meeting as “a marvelous encounter, as much from a personal point of view as a professional one.” They released La Mangouste (2008 Dargaud, 2014 Cinebook, The Mongoose), the first volume of the XIII Mystery collection, for which Meyer was awarded the Brussels St. Michel prize for illustration.

Meyer’s graphic style evolved radically in 2010 with the one-shot Page Noire, (2012 Futuropolis) scripted by Denis Lapière and Frank Giroud. He moved away from his tendency towards the rather spectacular frames typical of his style of graphic realism, and towards something simpler, less showy, in which the focus is on portraying the essence of the characters, their movement and their emotion.

In 2012, he and Xavier Dorison teamed up once again for the Nordic landscapes of the Asgard diptych (Dargaud Benelux). This project distanced Meyer from all his usual references of an urban, contemporary or futuristic world and plunged him into natural landscapes of gothic sublimity and hostility. He rose to the challenge and excelled, once again.

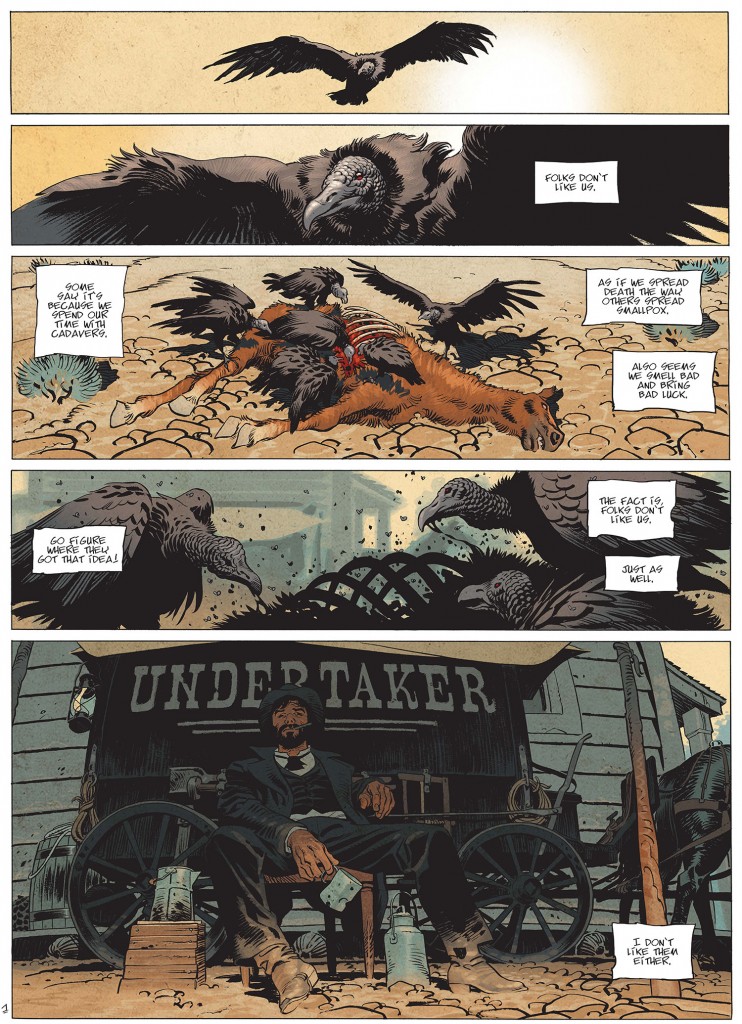

Asgard was soon followed by a third collaboration on the open series Undertaker, a western which enjoyed unprecedented success on its release (2015 Dargaud Benelux, 2016 Europe Comics).

For this latest series, Ralph employs once again the Franco-Belgian realism he masters so completely, marrying that classic style with a more contemporary vision in his mise-en-scène.

While both authors had dreamed for a long time of launching themselves into the rough-living, fast-shooting Wild West, they acknowledge that the complicatedness of the genre requires a certain degree of artistic maturity. With their last two releases, it’s quite clear that not only have they achieved that maturity, but also a rare creative fusion of two minds; they are present, intrusive and implicated in each other’s work.

We can look forward to the third installment of the Undertaker series in January 2017, and after that, who knows what’s next for this exceptional artist? One thing’s for sure, he’s certainly made his mother proud!

By Emma Wilson

Cover image from Undertaker © Meyer / Dorison / Dargaud