Comics play a fascinating and complex role in Spain. For over a century, the art form—known to the Spanish as “tebeos”—has been one of the country’s most attractive, evocative and endearing forms of entertainment. Thanks to the quality of their authors, Spanish comics deserve to be studied in depth. With this in mind, this history of Spanish comics celebrates the passion of the legion of collectors and enthusiasts who closely follow the development of the Ninth Art.

Spanish comics’ first steps can be situated in the mid-19th century when, as in the case of other countries, magazines and all kinds of weeklies opened their pages to this art form. Starting with the teachings of Apel.les Mestres (Cuentos vivos, 1898), there were numerous precursors to Spanish comics.

Antonio Martín dedicated his excellent Historia del comic español: 1875-1939 (Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 1978) to these precursors, a study that will guide our journey alongside another important reference: the text written by Antonio Lara in the catalog Tebeos: los primeros 100 años (Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional/Anaya, 1996, p. 27 and subsequent pages).

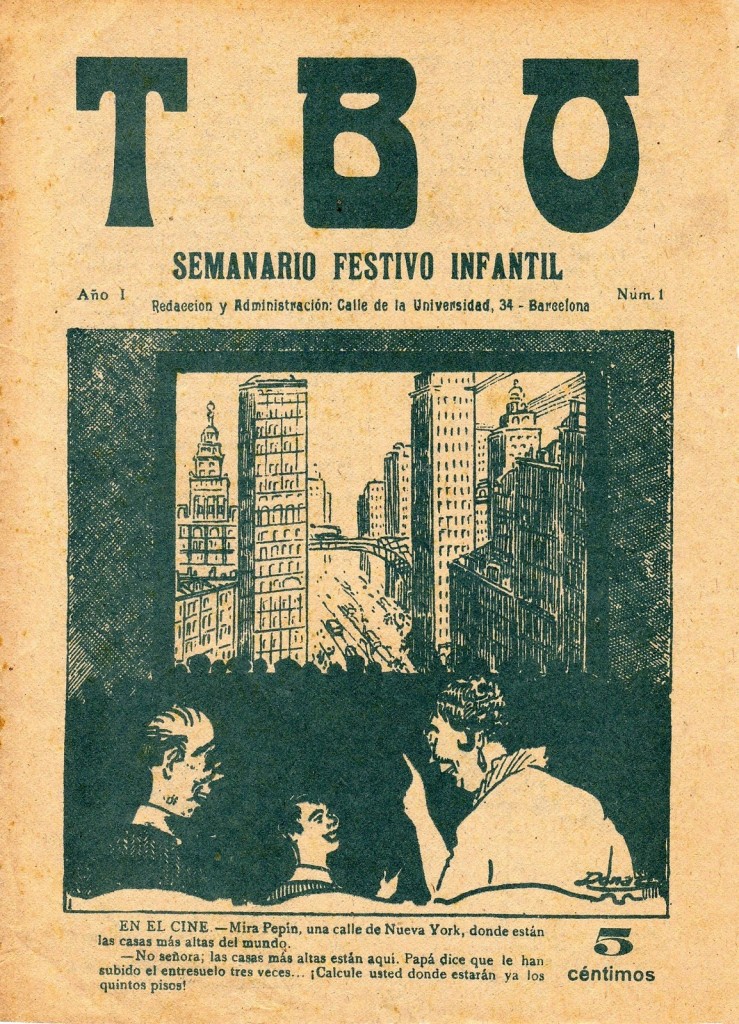

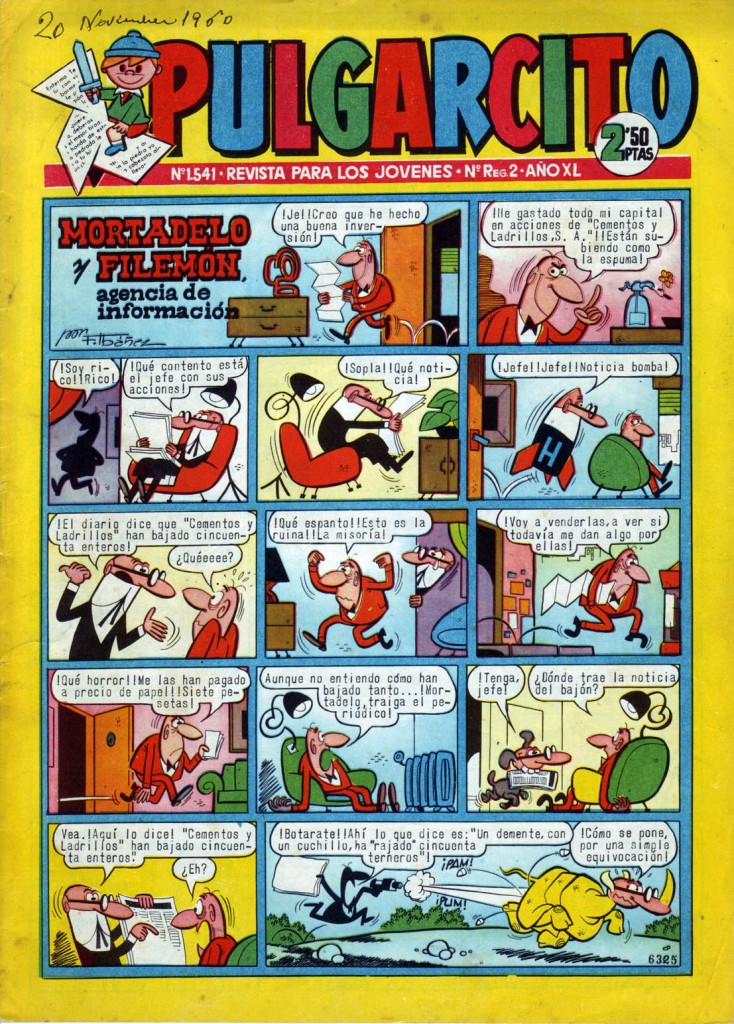

At first, children’s magazines served as the primary channel for all of the works created during the first decades of the 20th century. Starting with Patufet (1904), some of the classic names from the Spanish comics world would become household names during these years: Infancia (1910), TBO (1917), Pulgarcito (1921), Pinocho (1925) and Pocholo (1935). Nevertheless, the publication that would define this era was TBO (pronounced “tebeo”) from Spanish cartoonist Ricardo Opisso. At the same time, in Gutiérrez (1927) the comics world started to learn about the work of Miguel Mihura, Ricardo “K-Hito” García and Francisco López Rubio.

Competition from the United States set the commercial bar: “Evidently, in this regard, the short and single editions of Spanish magazines could not compete with the longer strips put out by American newspapers, and neither could Spanish illustrators limit their work to three or four strips per day. Nonetheless, comics started to proliferate and facilitated the emergence of noteworthy authors that managed to assimilate to the sudden advancements in the medium’s techniques, adopting and adapting them to their own personal style” (Vázquez de Parga, S.: “Primeras experiencias del cómic español,” in Coma, J., dir.: Historia de los cómics, Toutain, Barcelona, 1983. Volume II, p. 423).

During these years, Jaime Tomás (Vida, dimes y diretes del Mago de los Penetes, 1934), Francisco Darnís and José Canellas Casals, José Cabrero Arnal (Guerra en el país de los insectos, 1933) and Arturo Moreno (Punto negro en el país del juego, 1934; Palito y Pachito, 1937) played with both humor and caricature in their work.

Without a doubt, the most prolific of all was Salvador Mestres, who published his stories (El tesoro maldito, 1936; Aventuras de tres lanceros bengalíes, 1937; El Diablo Negro, 1948; Aventuras de Guerra, 1951) in several magazines of the era, such as Aventuras or Camaradas, although it was the publication Pocholo that proved to be the venue for some of his most important comics.

During the Civil War, comics continued to be published with regularity in Republican areas, while among the Franquistas a number of problems slowed down the process, until the publication of a few children’s weeklies, such as Pelayos (1936) and Flechas (1936), which joined forces two years later as Flechas y Pelayos.

After the war, children were very receptive to the consumption of comics and the resurgent industry was satisfied with the new regime’s ideological guidelines. As an important production center, Barcelona was the home base for cartoonists such as Jesús Blasco, Francisco Hidalgo, José Lafond and Gabriel “Gabi” Arnao. Meanwhile, in Madrid, the disappearance of Flechas y Pelayos was made up for with the emergence of other publications backed by the regime including Chicos (1940), Mis Chicas (1941) and El Gran Chicos (1945).

Something similar happened with the humor weekly La Ametralladora, which in 1941 gave way to La Codorniz, showcasing a variety of new work by Miguel Mihura, Tono, Enrique Herreros, Antonio Mingote, Serafín, Alvaro de la Iglesia, etc.

By the end of the 1940s, several publishing houses (Bruguera, Editorial Germán Plaza, Editorial Marco, Editorial Valenciana, Ediciones Toray, etc.), concerned about the future of the comics market, consolidated themselves. These were the years of the adventures of Cuto, published by Blasco in Chicos, and, above all, when Roberto Alcázar y Pedrín (1940)—two popular Spanish comic characters that were protagonists in a long series of comics created by the cartoonist Eduardo Vañó based on a concept developed by Juan B. Puerto—was at its peak.

Editorial Valenciana, one of the most successful publishing houses in the comics market during postwar Spain, launched two very popular comics, El Guerrero del Antifaz (1944) by Gago and the aforementioned Roberto Alcázar y Pedrín. The latter went into print in 1940 in landscape-format books with one or two complete adventures per issue.

These remarkably innocent tales introduced us to the protagonists Roberto Alcázar and Pedrín, whose adventures took place in the most remote and exotic places, where they had to chase villains of all kinds—from Asian pirates to South American bandits.

In a way, the two protagonists reminded readers of other characters, like Batman and Robin, who fell in line with the hero-sidekick model that had so much success in the international comics world after the 1930s. While Roberto Alcázar represented the model knight who protected and respected woman, Pedrín was the foul-mouthed, lower-class boy who preferred solving his problems with punches.

Between 1940 and 1975, 1,219 comics were published in landscape format. In 1966, a new collection called Extra appeared, which almost reached one hundred issues. This longevity, unique among Spanish comics, validated Vañó’s work beyond the ideological interpretations that emerged in the 1960s, attempting to highlight the Franquista facets of both Roberto Alcázar and Pedrín.

Eduardo Vañó, a sympathizer of the Spanish Republic, never understood how his creation was considered a stereotype of the Franquista dictatorship. These interpretations reached such extremes that some critics proposed that the protagonist’s physical appearance was inspired by that of Spanish noble José Antonio Primo de Rivera, when in fact it was a portrait of the author himself.

It is evident that the moral and social values of the series coincided with those set forth by various comics in the 1940s, but that is because the period’s popular culture adjusted to these values, not only in Spain but also in other countries.

Along the same lines, El Guerrero del Antifaz (1944) and El Pequeño Luchador (1945) by Manuel Gago represent a type of comic very characteristic of the postwar period and therefore marked by the political and social circumstances of the time. The same should be noted of Hazañas Bélicas (1948) by Guillermo Sánchez “Boixcar” Boix and the landscape-format comics of Juan García Iranzo (Dick Norton, 1944; El Capitán Coraje, 1946).

The work of cartoonists and writers such as Eugenio Giner (El museo siniestro, 1947), Antonio Bosch Penalva and Rafael González (Erik, el enigma viviente, 1947), Francisco Hidalgo (Skilled, 1947; Dick Sanders, 1948), Francisco Batet and José Mallorquí (El Coyote, 1947), Emilio Freixas and José Canellas Casals (El misterio del murciélago humano, 1945), Gabi Arnao (Jim Erizo y su Papá, 1947) and Angel Puigmiquel (El ladrón de pesadillas, 1948) appeared in the pages of Pulgarcito, El Campeón and especially Chicos.

The autarky years in Spain (1939-1959) generated humorous comics that satirized the difficulties of everyday life. This can be seen in El reporter Tribulete, que en todas partes se mete (1947) by Guillermo Cifré, Carpanta (1947), Zipi y Zape (1948), Petra, criada para todo (1951) and Blasa, portera de su casa (1957), all by José Escobar, and in Las hermanas Gilda (1949), La familia Cebolleta (1951) and Anacleto, agente secreto (1967) by Manuel Vázquez.

Much less edgy, the adventure comics followed the stereotypes and patterns consolidated by Hollywood cinema. This was the case of El Espadachín de Hierro (1949) by Manuel Gago, El justiciero fantasma (1949) by Angel Pardo, and Aventuras del F.B.I. (1951) by Luis Bermejo.

CONTINUE TO PART 2

From “Historia del cómic español” by Emilio C. García Fernández and Guzmán Urrero Peña for The Cult. Translated from the original Spanish by Storyline Creatives.

Header image from El Guerrero del Antifaz by Gago (Editorial Valenciana, 1944)