Italian author Teresa Radice and artist Stefano Turconi first worked together way back in 2003, on the Italian Disney magazine Topolino (Mickey Mouse). Nearly fifteen years later, their bond has solidified and comics fans are all the luckier for it, flocking to read the authors’ engaging graphic novels. The Europe Comics catalog features the wonderful adventures of Globetrotting Viola, originally published by Tunué. We got to sit down with these talented creators at Angoulême to talk about their past, present, and future, and what drives them to make comics.

Buongiorno! To start off with, why comics? Did you choose the profession, or did it choose you?

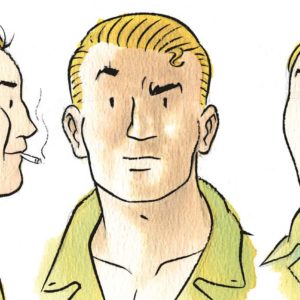

STEFANO TURCONI: Both a little bit, I think. Ever since I was a kid I’ve liked to draw, and also as a kid I began to read Astérix and [Italian comic weekly] Topolino. I actually learned to draw copying their characters, and from that point on it happened all by itself. At a very young age I decided, “I want to do that.”

And your parents didn’t tell you, “But why can’t you find a real job?”

TURCONI: My parents were desperate, because I didn’t find any real jobs, exactly. But they finally accepted it because I was talented at drawing, and they knew it, they said it themselves. And so they caved. Also, in the little town where I lived, there was a comic book artist who illustrated [monthly western comic] Tex Willer. So there was an example of someone making a living doing comics. There was a precedent. This was an opening for me, and beyond that, I’ve always read comics and illustrated books.

TERESA RADICE: On my side, I think it was comics that found me. Ever since I was little, for me too, I’ve always loved to read—they tell me I started to read at three—and I’m also an only child. I often felt alone, so I sought the company of books. I have a young uncle who was very much into Topolino and another Italian comic, Alan Ford, and he had a chest full of comics. And I pulled things from the chest and read. So I think it was a bit comics that found me. And then, a bit by chance, it happened that I started to write for comic books in college. I saw there was a comic scriptwriting course, and I knew all the Disney characters by heart since I’d grown up in that universe, and that’s how it all got started. Really I’ve always wanted to tell stories, whether it’s for kids or adults. Just tell stories.

That was our next question. How did you decide to focus on kids? Did you also ever think about creating books for an adult audience, or for even younger kids?

TURCONI: In fact, we stretch quite a bit. We started with kids. By training, and in terms of style, my illustrations are a bit more humorous, and less realistic. I don’t know how to do realistic, I’m just not capable. Even the things we do for adults, the style isn’t purely realistic, it’s more of a middle road. So you can see some influences from another genre. But yes, we do things for very young children, older kids, and also for adults.

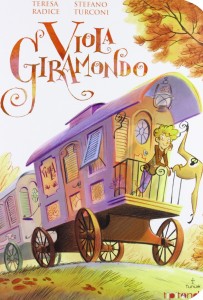

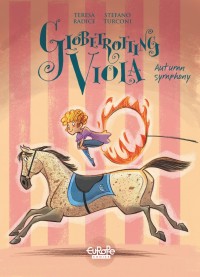

RADICE: We got started as, and became known as, children’s authors because we worked many years—almost twenty for Stefano, and fifteen for me—for Topolino, a magazine that puts out six or seven Disney comics each week [Ed’s note: “Topolino” is the Italian name for Mickey Mouse]. So we started to become known by its readers, and we were always seen as children’s authors. And then the first thing we did outside of Disney was Viola Giramondo (Tunué, 2013; Globetrotting Viola in English by Europe Comics, 2016), which was also for kids. In general, though, we’ve always had a desire to tell stories to people, whether kids or adults.

And now Viola Giramondo has been published in France as well [as Violette autour du monde, Dargaud, 2016]. Could you compare the comic world and comic market in France and Italy? How do you see the situation in Italy?

TURCONI: First off there’s an enormous difference in the numbers. In terms of readers, I wouldn’t say the comic market in Italy is tiny—there are much smaller ones out there—but it’s not as big as in France. The French comic market is truly enormous. There’s also a lot of attention paid to comics by the state and other cultural entities, it’s really considered to be a form of literature. In Italy I think we’re getting there bit by bit, with a lot of difficulty. Graphic novels are now starting to dislodge the idea that comics are just for kids, and show that anyone can read them. There are some really important stories told in the form of comics. It’s simply another way of telling a story—just as you can write a novel in prose, you can also do it with comics. They have the same dignity. And so for now that’s also a key difference between the two countries.

RADICE: Absolutely. But other than that, in the readers we meet we really don’t see any major differences. When readers are passionate, they’ll come seek you out, whether it’s in Italy or France. It’s really a gift for us to meet the people on the other side, because we work at home. When the book is finished, one chapter is over for us but another begins, as we go meet people we don’t know, people the book itself (which is like a kid for us) doesn’t know. It’s a new life for the book that depends on the affection readers have for it. I imagine it’s a bit like the movies, where the film is finished and then it continues its life in the hands of the audience.

The two of you work together already, but is there anyone you dream of working with, dead or alive? An idol, someone who intrigues you? Someone like Neil Gaiman, for example, or…

RADICE: Neil Gaiman, exactly! More than anything I love his lectures, all of the work he does about the importance of reading for children. I work by hand, I write everything by hand, I really don’t like technology—but on my computer I have a folder titled “Neil Gaiman” where I put all of his lectures and talks, because I find it to be something that truly opens your heart. He is a legend to me simply for that. Before his books, even. And then in France, we’re wild about [artist and writer] Cyril Pedrosa. The kind of fans where, when I met him at the gala dinner in Lucca [at the Comics & Games convention], I was overtaken with emotion. I must have made a dreadful impression, but I asked him, “Could we take a picture together, to make my husband jealous?”

TURCONI: Right, because I wasn’t there. The first thing she says when she gets home is, “Check it out, I’m friends with Pedrosa.”

RADICE: He must have thought I was crazy! In any case, we’re major fans of his, from the very beginning.

TURCONI: Starting with Ring Circus. It was the first book I bought the first time I came to Angoulême in 1998, and its style really struck me.

RADICE: We have his books in French and Italian.

And how do you see the future? Teresa, you said you’re not a fan of technology, but do you see a positive side to digital, do you think it could help comics?

RADICE: I think it could help in some cases, like when readers have a hard time relating to a certain book, which is maybe different from their way of thinking, their tastes, their way of seeing things. E-books can be a positive thing because they allow you to give new books a chance, ones you might hesitate to buy in print. And then hopefully afterward you might also give the print book a shot.

And your future projects? Do you still have lots of stories ready to be told, or do they come to you suddenly and unexpectedly?

RADICE: We have more stories than drawers! Every time we start a new project we’re already thinking about the next story we want to tell. Perhaps not complete stories, but little sparks, or an atmosphere, or a theme. It’s a wonderful thing, because working together is like walking along together, each book is a step toward the next thing. Or maybe it’s like climbing a mountain—you reach one milestone, you look beyond, and you say, all right, let’s continue.

TURCONI: We also like looking for new historical settings. Not to make historical comic books, but ones that are set in historical periods, rather than a fantasy or sci-fi world, or the present. So when we’re thinking of our next books, we ask ourselves, where do we want to go this time? The Middle Ages, maybe medieval Tuscany—we have a project with this kind of setting, and another book set in Russia during World War II. The wonderful thing then is to read about the subject and, whenever possible, to visit these places. For our big graphic novel set in England [Ed.’s note: Il porto proibito, The Forbidden Port], we went to England to the places where the book was set.

RADICE: The research phase is like a preliminary journey before the real journey, and it’s a beautiful thing. It’s not like when you’re studying at school. You’re the one who decides where to go, you discover new things, and these things lead you to other things. It’s wonderful. The book is a journey that lasts two, two-and-a-half years before it comes out.

Viola Giramondo has won the Premio Boscarato in Italy, and was a finalist at Angoulême in 2015 (Séléction Jeunesse). For more about the authors, you may also head over to their blog, La casa senza nord (in Italian).

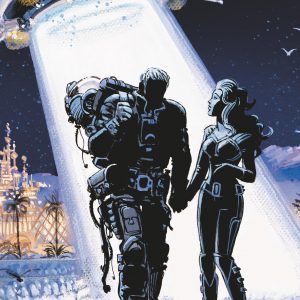

Cover image from Globetrotting Viola V1 © Teresa Radice and Stefano Turconi