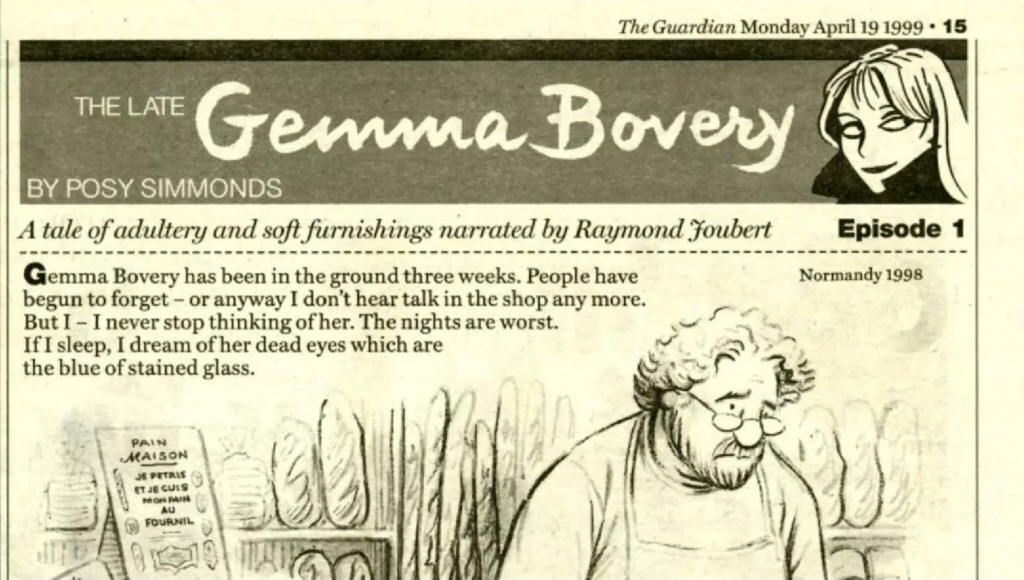

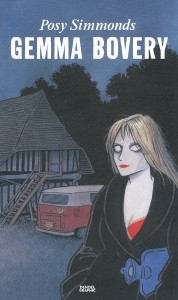

British author and illustrator Posy Simmonds, born in Berkshire, England, is best known for her long-running collaboration with The Guardian, which published her series Gemma Bovery and Tamara Drewe. And she also happens to be a wonderful person and a delight to chat with. We were lucky enough to meet with her at the beautiful city hall of Angoulême during this year’s festival, and invite you to check out our interview below!

Welcome to Angoulême! Are you a regular visitor of the book fair in Angoulême?

I’ve been here three times before, but not very recently. The last time was in 2008.

And how does it feel now to come here as the president of the jury?

It feels extraordinary. I’m going to be very correct and very dignified and very fair. [Laughs]

So do you have any favorites already?

My lips are sealed. I can’t say.

I had to try my luck.

I must say, the short list for the main prize—it’s a very high standard.

It’s very different this year as well, because there are only three finalists as opposed to the long list that they had every year.

Over Christmas I read about 60 books and we had to choose ten. For the main prize there’s one winner and then there are other prizes for different categories.

Jumping a bit from Angoulême, what do you think is the quintessential difference between the British comics and comics culture and that of the francophone countries? Because you’ve had the chance to live in both countries and see for yourself—you studied in Paris at the Sorbonne.

Yes I did, when I was seventeen. Of course in France, bande dessinée is so immense that when I first came to Angoulême I couldn’t believe it. In England we lag behind a lot, but now it’s sort of caught up. There are big festivals in Britain, there are comic shops everywhere. In France you can buy bandes dessinées in supermarkets, and I don’t think we’ve got there yet in England. And generally, historically, comics were thought to be for children and after a certain age you grew out of them. That certainly was the case when I was a child. You were allowed to read them but you were meant to read proper books after a certain age. But I read a lot as a child.

So which ones were your favorites?

I was lucky enough to know American children, because it was not long after the war and in my village there were lots of children of American servicemen. They’d go to the American air base and buy piles of comics, and when they were finished with them they used to give them all to me. I had stacks of Superman and Mickey Mouse and Casper the Friendly Ghost and Blondie and Little Nancy – I had all of them. And occasionally, some horror comics got in. I would have been eight, nine, and I can remember my mother saying, “What are you reading?” because I was going, “Ugh!” One of the characters was being squashed in an olive press, and she said, “Oh, really,” and she took it.

Jumping to another question, where do you find inspiration for your work? And are there any artists that inspired you?

When I was a student, I liked very much the cartoonists of the 18th century in Britain, because Britain has a very long tradition of political cartoonists. [William] Hogarth and [Thomas] Rowlandson were my particular gods. And when I was a student there was a British cartoonist called Ronald Searle, and he lived in France for a long time and drew for Le Monde. Saul Steinberg. They’re all the heroes of when I was a student. And obviously all the comics that I’d read as a child—

Even the horror ones?

Even the horror ones. If I drew, I always had a balloon, or a bit of text. I always associated image with word. So where I get my ideas from—I wish I knew, because then I could do it every time—but certainly I always keep a notebook, I draw what I see. People are kind enough to talk very loudly on their phones, and sometimes they say the most extraordinary things. So you write it down.

You mentioned before in one of your previous interviews that drawing comes easier to you than writing. Is that still true?

I’ve always worked for the press, and the work I did then mainly had balloons, so I’m quite used to dialogue. But when it came to doing the series Gemma Bovery, which began in the paper, they [The Guardian] only gave me a hundred episodes. I had to cram in lots of story, and that was one of the reasons why I wrote so much. To begin with I found the writing very difficult to get it exactly as I wanted it, but after a certain time I knew what was going to be an image and what was going to be in text. Text is very useful for saying things about, he was married three times, he hated his wife, he loved his dog, and today he’s hungover. It was good about history. And the image was very good for the mise en scène, for the weather, and for important dialogues.

And is there perhaps a comics writer or any other writer dead or alive that you would have loved to collaborate with and illustrate their work?

That’s a tricky questions. I was about to say Dickens, but his characters are very caricatured, they’re quite over-written. There’s an English author called Evelyn Waugh, he died I think in the 1960s [ed.’s note: 1966]. His books were quite satirical and funny but also quite savage as well.

How do you see the future of comics, in general? And perhaps its place in society, with all the current social and political changes?

I think now more than ever we need comics, because they’re so democratic and their reach is enormous. They stretch from the United States via Britain and Ireland, to France, Italy, places where they’ve been huge forever, and then right across to India, Asia, the Russians are doing it, the Chinese, the Koreans. I mean, it’s everywhere. It’s an international language I think.

And what are your thoughts on digital comics?

I’m a bit of a dinosaur, and I’ve only had a computer for four years, and I haven’t got a– a whatever it is, a—

A tablet.

A tablet, so I’m a bit pathetic. But I’m not a Luddite, I’ve been shown a friend’s, and you can do all kinds of things. Maybe when I’m grown up…

And do you have any advice or words of wisdom for aspiring comics creators working today?

I would say always carry a notebook, or maybe if you’ve got one, a tablet—for me, a dinosaur, it’s a notebook—and listen, and look. Also read as much as you can, because I think that adds a kind of fluidity, especially if you write. But I think listening to people and looking is a good thing.

If you hadn’t become a comics creator, what do you think you would have become?

That’s very difficult. When I was seven I wanted to be a cowboy. I didn’t do that.

But maybe when you grow up?

[Laughs] I mean, I was quite interested in archaeology, so I might have been an archaeologist. I don’t know, I’ve always liked writing, I’ve always liked drawing, so it’s rather impossible to say.

So what are you working on now?

I’m working on another graphic novel. My book is rather long in coming, but I hope I’ll finish it soon.

So your lips are still sealed.

My lips are sealed, yes…

Cover image from Tamara Drewe © Posy Simmonds