Such nice “Negroes”

Eighty years after the publication of Tintin in the Congo, Bienvenu Mbutu Mondondo, a Congolese expat, sued Casterman and Moulinsart. He claimed the publication was racist, and demanded that it be taken off the shelves or, at the very least, that a foreword be added to include the historical background. And while the censors had never made an issue of it, more Belgian comic books were soon called out for the stereotypical way they had portrayed black people.

“It’s kind of these negroes to carry us so victoriously to our hotel,” Tintin says. As he disembarks from a long boat journey, the ginger-haired journalist dispatched from the newspaper Le Vingtième Siècle finds a mixed crowd of sparsely clothed Congolese ready to escort him with much fanfare to his hotel. The scene takes place in 1930. Hergé had at the time published just one other Tintin story: Tintin in the Land of the Soviets. Somehow, everything in Tintin in the Congo leads us to assume that the comic book hero’s popularity has already reached sub-Saharan Africa.

In Tintin in the Congo, the adventure kicks into gear on page 20. Our protagonist hires a black boy named Coco to be his helper. “Yes, mistah. Good, mistah,” he respectfully repeats to the tall, white Belgian hero who wears a colonial helmet and carries an impressive shotgun. Later on, Tintin aims his gun at an antelope in the savanna. He fires. Missed! He fires again… Missed again! Or that’s what it seems like at first, until he comes across an entire pile of dead antelopes he’s inadvertently shot. The carnage doesn’t stop there! In the next page, he shoots down a monkey and, a couple of pages later, a giant boa constrictor, then an elephant whose ivory tusks he takes. Killing a rhino may seem hard to pull off, but not when you’re Tintin. He drills a hole in the animal’s skin and blows it up with dynamite, without batting an eyelid. He doesn’t approach the black community with any more subtlety. References to Belgium and the advantages of colonization abound, especially when Tintin talks to African schoolchildren about their homeland: Belgium. Later on, he prays to God to help him when he is under attack.

These scenes are exactly why Bienvenu Mbutu Mondondo decided to sue the publisher, eighty years following its release. In 2011, he demanded that the publication be taken off the shelves or, at the very least, that a foreword be added to provide crucial historical context.

When Tintin in the Congo was published, Hergé was 24 years old and nobody cared. The publication had sparked zero controversy at the time. It was much later that the passages came across as shocking to black and white people alike. “Back then, it was considered normal for a country to have colonies,” said Hergé in his defense. “Here, in Belgium, you had the Colonial Lottery, and a spirited black boy would introduce the commercial breaks at the cinema. We had a Colonies Street, coffee shops named ‘The Colonial’ and hotel bellboys tended to be black. You could even buy ‘Negrito’ shoe polish.”

Remorse

“A lot of things could have been done differently,” wrote Hergé’s biographer Pierre Assouline in 1996 (author of the book Hergé.) He emphasized, however, that Hergé had shown weakness, and allowed himself to be swayed by the ideas of the editor in chief at Le Vingtième Siècle, Norbert Wallez, who also happened to be a highly conservative priest. Following his work on the first volume, Hergé had wanted Tintin to meet the Indians next, but Wallez was against it. The Congo was in desperate need of publicity. The PR effort had started two years earlier with the first royal visit by Albert I and Elizabeth. Wallez was keen to propagate colonial thinking as early on as possible, and what better educational tool than a harmless volume of Tintin?

There were certain scenes that Hergé came to regret. “Both Tintin in the Congo and Tintin in the Land of the Soviets were greatly influenced by the prejudiced attitudes of my bourgeois social circle. It was 1930. I was no better than those who at the time made ignorant statements like ‘Negroes are infantile and stupid’ and that ‘they should consider themselves lucky we took over.’ I was saturated with those ideas as I was drawing Africans, completely blinded by the paternalism that prevailed in Belgium at the time.”

Fair enough. But we can’t help but notice that the colonial references aren’t much subtler in the revised 1946 version. Africans no longer call Tintin “mistah,” they call him “mister.” In a later version, this becomes “massa.” Other than that, the changes are limited in scope. Crucially, the text had been scoured of countless references to Belgium and Belgian politics. The move was opportunistic, more than anything, because the series had at that point become a hit Europe-wide, and the toning-down was aimed at appeasing neighboring countries. References to colonial domination were deleted, as was the scene where Tintin addresses young Africans about their motherland, Belgium. In the new version, Belgium becomes Europe and the Congo becomes Africa. Even on the cover of the Dutch-language version. The names of newspapers appearing in the first version like The Bush, Africa, and The Colonial, were kept in the second and all subsequent versions.

Above all, one phrase that is more or less maintained is “little negro.” The witch doctor continues to sport a saucepan on his head like a hat. Tintin is presented as the great white hunter who collects trophies across all foreign editions of the book, save one. The Scandinavian publisher asked Hergé to change the scene in which a rhinoceros is filled with dynamite and blown up. Instead, it makes an escape and survives meeting the reporter. The fact remains that Hergé could have made a lot of changes, especially as the new color version produced in 1946 was cut down to 64 pages.

In 2012, the Court of Appeal put an unsuccessful end to the suit brought by Bienvenu Mbutu Mondondo and the Representative Council of France’s Black Associations. The applicants maintained that it was a shame that the defendants hadn’t owned up to the error of their ways unprompted. “They don’t want to embarrass themselves in front of black people,” Mbutu Mondondo confirmed. “That’s why they refuse to add an introduction explaining the historical background, like they do in the UK and the US. In those countries, publications like these have been removed from children’s libraries.”

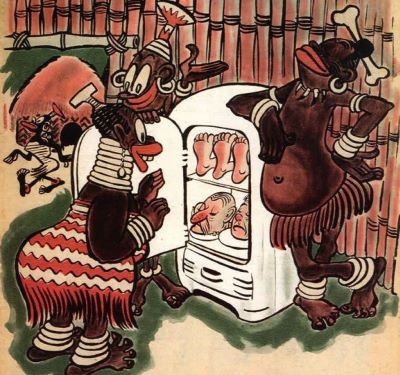

Thick lips

Hergé was one of a number of Belgian comic book writers criticized for his portrayal of black people. Inevitable, really, as comics writers peddled in stereotypes more than realist writers. In 1976, Greg announced that the next story featuring his star character, Achille Talon, would be set in Africa. “I was excited to do it. Everyone avoids writing stories taking place in Africa. Especially funny ones! It’s like reverse racism.” He points out that he “had always been in the habit of drawing idiotic white people.” For example, Talon and his neighbor Lefuneste. “So when Talon goes to Africa, the black people he meets also have to be a bunch of idiots.” Greg makes a wider point, saying that “black people always seem to be portrayed as beautiful and smart, because doing otherwise puts the writer at risk of being called a racist. But I don’t discriminate at all when I write, I am completely impartial. You can find all kinds of bastards in my stories: white, black, Asian, Jewish or Arab. My characters are all crazy, so the black ones must be too. If I didn’t follow my own rules, I’d be a hypocrite.”

In that same interview, Greg openly talked about the issue of portraying Native Americans in Hermann’s western series Comanche, for which he wrote the script. “I came up against the same problem with Comanche. These days, Indians must be shown as good, and white people as the villains who stole their lands and tried to brutally wipe them out. But just go ahead and open up a history book covering the period in which Comanche is set! Let me tell you, some Indians were really savage, cruel, and bloodthirsty. That side of the story also needs to be told, otherwise you’re only being partially truthful.”

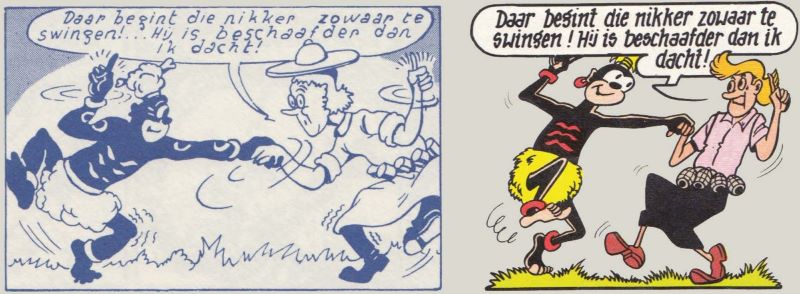

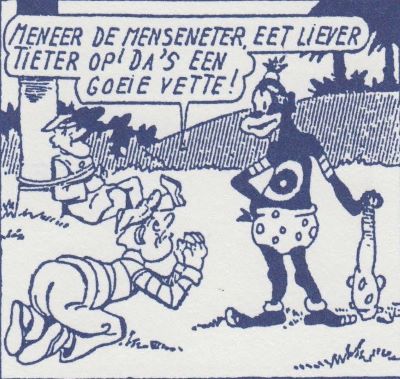

In Flanders, Jef Nys and Marc Sleen experienced the heaviest criticism for the way they depicted black people, in Jommeke (Jeremy) and Nero respectively. “As if black people don’t have thick lips,” says Nys, wryly. “They do, for goodness sake! But that’s how black people were caricatured back in the day.” He sums up: “So be it! The only thing those critics achieved was to stop me from including drawings of black people in my books.”

“They accused me of racism because I had drawn Arab women being abusive in a hospital setting,” explained Sleen. “The Standaard’s journalists hung my drawings on a bulletin board, and accused me of racism. Where’s it going to end? They also judged me for drawing black people with thick lips. Back then, everything was criticized. You couldn’t mess with black people or priests. Eventually, I couldn’t even caricature Arabs and Walloons, let alone the Flemish.”

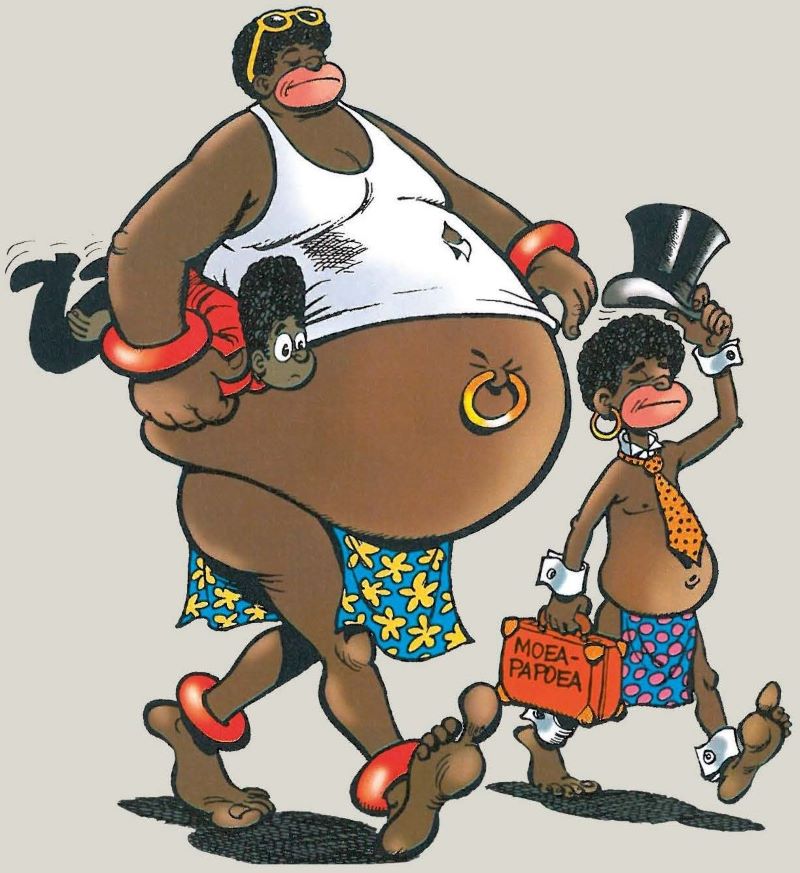

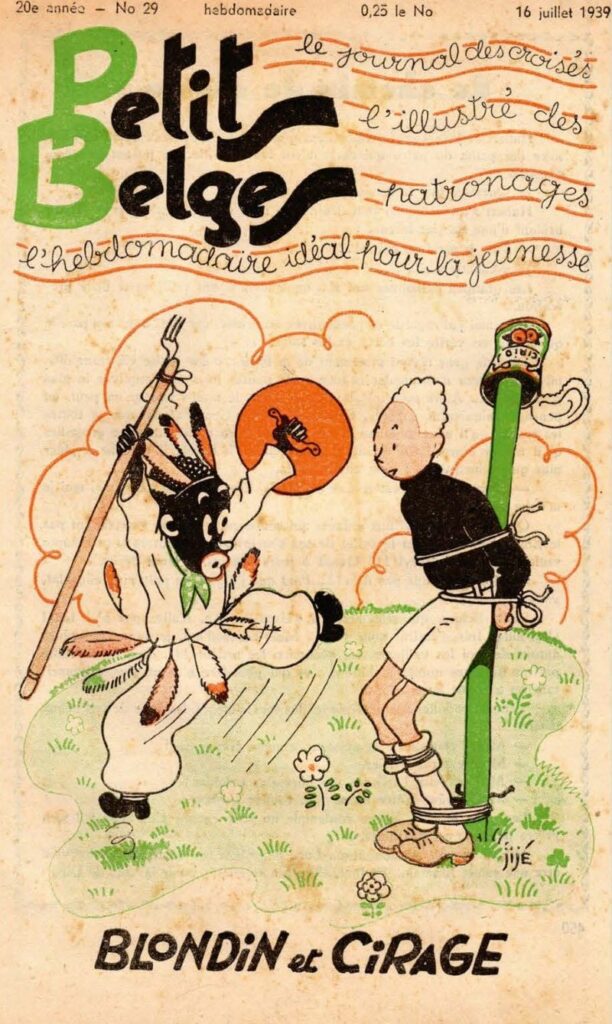

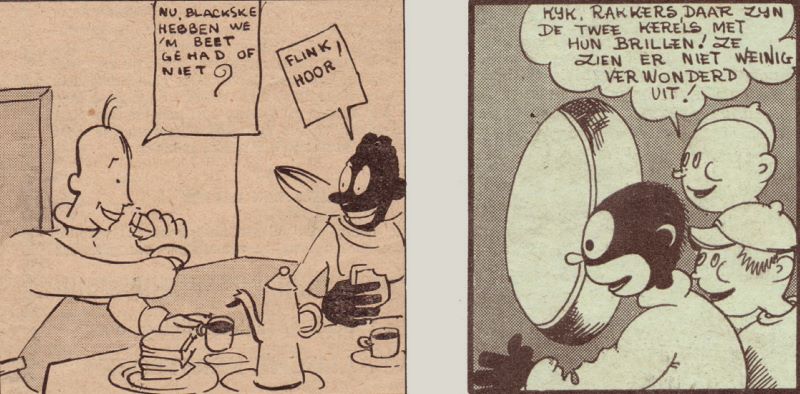

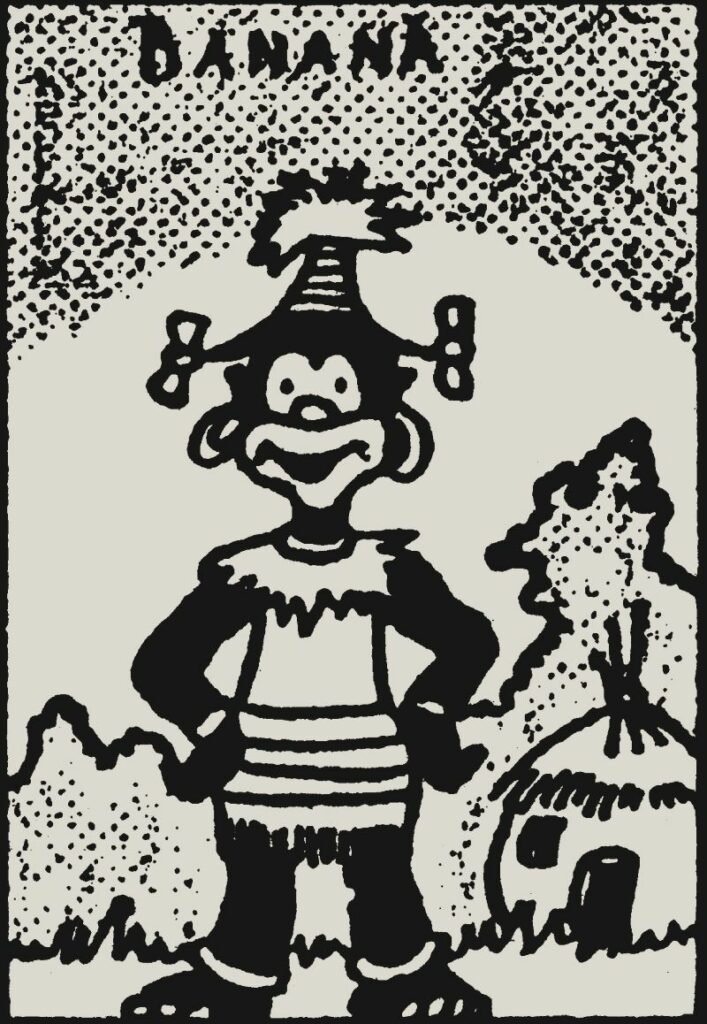

But black people weren’t always portrayed as stereotypes and clichés in the first half of the twentieth century; sometimes they caught a break with positive depictions instead. Shortly after the Second World War, Jijé decided that one of his young protagonists in Blondin et Cirage should be white and the other one black. Even earlier, in 1932, the newspaper Ons Volkske (Our Little People) had launched a series by artist Pink (Eugeen Hermans) called Suske en Blackske, which featured a young black boy in the little gang of characters. His name was Witte (White). Pink said he came from the Congo. But the most famous Belgian adventure series that included a young black protagonist is La Ribambelle. Initially drawn by Jo-El Azara, based on an idea by Franquin, the series clearly drew inspiration from pre-war American comic books, such as Winnie Winkle the Breadwinner (1920) by Martin Branner, and from the series of short films Our Gang (1922). Winnie Winkle was bold enough to present African Americans and white Americans on equal terms. Roba rebooted the La Ribambelle series and kept the strip up for many years by giving the gang an international flavor, adding foreign characters such as a pair of Japanese twins, a Scot and a black boy named Dizzy.

A loaded term

Is the term “negro” so shameful and offensive? Yes and no. “Look up the dictionary definition of the word,” said Flemish author Judith Vanistendael in 2007. “It has nothing to do with racism.” She is the author of the graphic novel De maagd en de neger, a semi-biographical story about her brief marriage to Abou, an asylum-seeker from Togo. “The term is only perceived as negative by the closed-minded and politically correct. By people who have never met someone black and are terrified of committing a faux pas, so they avoid using the term at all costs. You can’t make a joke or be caustic anymore.”

But not everybody appreciates the term “negro” in a title… “Looking back, I had second thoughts. Soon after the book was published, I was called to speak at WOMEN Inc., an organization concerned with women’s rights and gender issues. The title had infuriated one Surinamese woman, which gave me pause and made me a little ashamed. She thought it had been done to create controversy and sell more copies, which is, of course, not at all the case. I’m not looking to create controversy for controversy’s sake! I would never use the term ‘negro’ to refer to a black person if it were to cause offense. It’s true, I’m not black myself… so maybe I’m not even entitled to use the term? Anyhow, I still think the title is a good one. It reveals a lot. Specifically, our triggers and sensibilities, as well as our self-interest, which we prioritize in the way we deal with refugees.”

In French, the title was translated as La Jeune Fille et le Nègre, in Spanish, Sofía y el negro. No one even debated the word “negro” in these cases. The English translation, however, was a whole other story. “It’s a hugely loaded term in English. So, the book was published under a much subtler title: Dance by the Light of the Moon.”

What’s more, Abou, Vanistendael’s ex-husband, actually enjoyed Tintin in the Congo. “It was one of his favorite volumes. He understood the humor,” she added. “If you don’t think it’s funny, there’s something wrong with you. In any case, I used to call Abou ‘my little negro’.”

Excerpt from La Belgique dessinée, by Geert De Weyer (Ballon Media, 2015).

Translated by Storyline Creatives.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily represent the views of Europe Comics.

Header image: [Chick Bill] © Tibet / Le Lombard, 1954