When the Belgian comic strip made its first appearance, a long time ago, speech and thought bubbles hadn’t been invented yet. Lacking reference points, the first Belgian authors eagerly followed the developments of this new art form coming from the United States. However, even though both Hergé and Willy Vandersteen were deeply influenced by American comic strips, Belgian comic strips, in both Flemish and French, evolved separately and in their own ways, each with its own masters, specific codes and areas of interest.

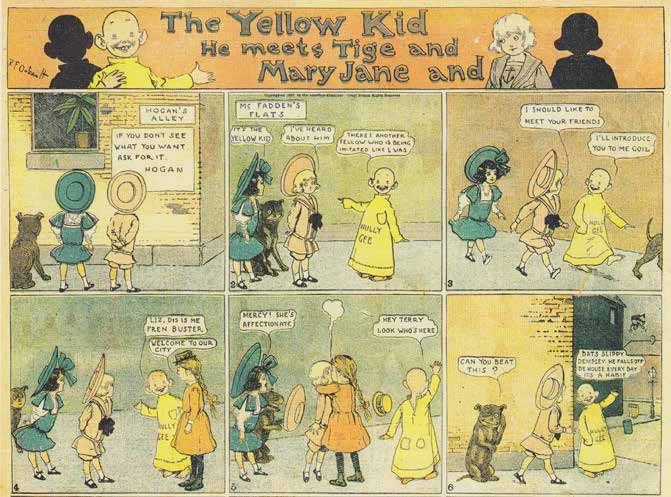

In 1895, readers of the American newspaper The New York World were surprised to discover a street urchin nicknamed the Yellow Kid. With his piercing blue eyes, his characteristic oversized canary-yellow nightshirt, his huge low-hanging ears and cue ball head, he created a stir. Despite his somewhat mundane adventures, the Yellow Kid was a unique character for his time. His spiritual father, the science-fiction illustrator Richard Felton Outcault, named him Mickey Dugan and described him as an Irish boy from New York’s Lower East Side, which at the time was the final destination for millions of immigrants from every corner of the world in search of a better life. Mickey Dugan’s adventures were usually short tales using the city and its surroundings as a backdrop. As for the stories, they remained fairly basic: Mickey might be smothered in cigar smoke and disappear into the haze while someone tries to take his picture. Or, Mickey might be looking somewhere else when a stray dog bites off a piece of his nightshirt. These were the sorts of tangles Mickey Dugan, the Yellow Kid, got into.

Because speech balloons didn’t appear much in the Yellow Kid, not all scholars consider it a true comic strip. At most, some panels showed animals (goats, parrots, etc.) talking to Mickey through the expedient of tiny balloons escaping their mouths or beaks. But it was mainly through his yellow nightshirt, which advertised his thoughts, that the Kid addressed readers.

Be that as it may, in 1995, in order to celebrate the centenary of what they considered to be the first comic strip character in the world, Americans decided that the Yellow Kid’s creation also marked the invention of comic strips. Did this date satisfy everyone? Not quite. The European comic industry wasn’t happy with this unilateral declaration. According to Charles Dierick, former artistic director of the Brussels’ Comic Strip Museum (Musée de la Bande Dessinée), while the Yellow Kid — Mickey for short— was indeed the first comic strip hero, the date of his creation is more problematic. Indeed, Dierick presents four conditions for a work to be considered a comic strip. “Modern comic strips — with emphasis on ‘modern’— are characterized by a segmentation in panels, in which the story is told by balloons, or speech bubbles. Moreover, a comic strip must be published in a mass-produced periodical publication, such as a newspaper. However, when it was first published, The Yellow Kid was little more than a single drawing without balloons. The corresponding text was written within frames suspended on the walls, on the characters’ shirts, or on Mickey Dugan’s yellow nightshirt. It wasn’t until 1896 that the Yellow Kid’s stories started being divided into three panels, with speech balloons. That was the point at which it could be considered a comic strip.”

Europe — and particularly Belgium — seemed bent on boycotting the centennial celebrations until the last moment, going so far as to refuse to organize any sort of dedicated event. In the end, after long negotiations, Belgium would go on to celebrate the first century of comic strips after all, but a year later, in 1996. On this occasion, at the initiative of the Comic Strip Museum, Morris, creator of Lucky Luke, also celebrating its 50th year, presided over the foundation of the Committee for the Centenary of Comic Strips (Comité pour le centenaire de la bande dessinée), and Belgium was declared the land of comic strips with the support of its ministries and official tourism boards. According to the Comic Strip Museum, a major factor in this designation was the leading role played by Brussels and Belgium on the international scene. But, as outlined by a committee member, having a diverging opinion is not a lack of respect: “We do not want to monopolize this prestigious anniversary. The Committee only wishes to play a coordinating role.”

The rat race

The various discussion panels held for the centenary gave rise to agitated arguments over the real age and definition of comic strips. They soon revealed rampant discord among the international experts. Was The Yellow Kid the first ever comic strip hero? Gossips would claim there are about as many opinions as there are comic strip theorists. European exegetes date the first appearance of comic strips all the way back to the stories told in images by the Swiss engraver Rodolphe Töpffer (1799-1846). As early as 1845, Töpffer declared the following regarding his critics: “Those stories told in images, despised by the critics and that intellectuals do not take seriously, have had a great influence over the centuries, maybe even more than traditional written literature.” He went even further, saying that the fact that the main enthusiasts of these stories were “children and proletarians” was a virtue rather than a flaw.

Others would argue in favor of the popular prints for children which flourished in the 19th century or the “newspapers for youth,” which appeared soon after. According to some scholars, even the medieval representations of the lives of saints or the Bayeux tapestry, depicting the exploits of William the Conqueror at the battle of Hastings, could be considered comic strips. In his international bestseller Understanding Comics, American artist and comics theorist Scott McCloud boldly sets the date at 3,000 years prior to the “official” creation. According to him, the first traces of successive images forming a story can be found in a 36-foot-long pre-Columbian manuscript discovered in 1519.

In which case, if these are comic strips, why not consider the Egyptian hieroglyphs? And what about the British painter William Hogarth (1697-1764)? He, too, could be considered the precursor to Willy and Wanda (Suske en Wiske), Tintin and Spirou. However, regarding modern comic strips, McCloud agrees that Töpffer could well be the founding father. Even the great poet Goethe was a fan of Töpffer’s “illustrated stories.”

But wait, the other specialists roar, what do you make of prehistoric cave paintings? They, too, are graphic attempts to tell a story by means of images, without a text element. And here we see the main counter-argument: in order to call it a comic strip, there must be a relationship between text, image, rhythm and technical reproduction.

Fair enough, but this condition is also met by the works of Wilhelm Busch (1832-1908). And, frankly, are balloons really such a fundamental element in defining a real comic strip? If this was the case, it would imply that many contemporary works, such as Arzach, the wordless classic from the French master illustrator Moebius, would fall outside this category. So all we can say for sure is that the case is far from being closed!.

Hogan’s Alley

Let’s go back to Hogan’s Alley, where our dear friend Mickey hangs his nightshirt out to dry on sunny days. What is certain, all things considered, is that this energetic young man played a crucial role in the development of the comic strip as a medium. Created at a time when cinemas, amusement parks and music halls were making their first appearances, the series The Yellow Kidwas so popular that it became a weapon in the fierce battle between the two biggest press moguls of the time: The New York World’s Joseph Pulitzer and The New York Journal’s William Randolph Hearst. A year after the series first appeared in the pages of Pulitzer’s paper, Hearst stole it from his competitor. The reason behind this rivalry was simple: the daily publication of a popular series in a newspaper boosted sales. It was the golden age of illustrators. At the time, publishers and syndicates fought a merciless countrywide war to draw in the most popular illustrators. And we haven’t even mentioned the merchandise derived from their work! Soap, magazine covers, tin toys and even cigars—Mickey Dugan’s face was everywhere! For the readers of the late 19th century, the Yellow Kid was what Mickey Mouse, Bugs Bunny or Pokemon would be for future generations. In 1995, a century to the day from its first publication, the United States Postal Service even dedicated a stamp to the urchin from New York and his (non-) adventures were once again reprinted.

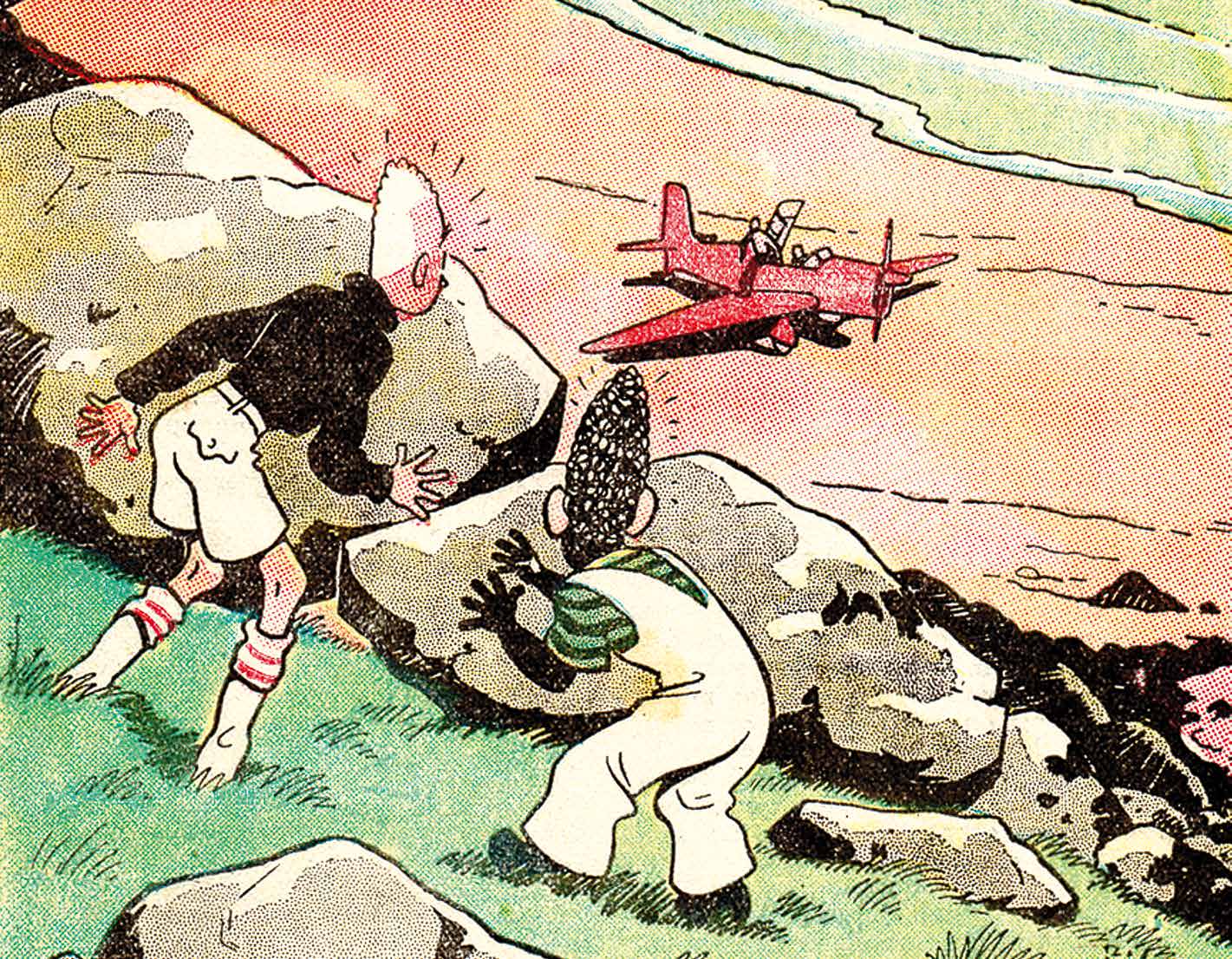

In the wake of The Yellow Kid, many illustrated heroes were created for syndicated newspapers: Little Jimmy, Buster Brown, Happy Hooligan and The Katzenjammer Kids. But what doubtlessly launched the US comics industry, ten years after the appearance of The Yellow Kid, was Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo in Slumberland. In this fantasy-filled series, printed full-page, and later on in color, the author draws the dreamy adventures of a little boy who travels above New York’s skyscrapers in his bed, meeting the strange creatures of Slumberland. The stories consistently end with a panel depicting Nemo falling out of his bed, startled out of sleep. It was just a dream! In 1911, just a year after its first publication, the series also became the subject of an editorial battle between the great American newspapers The New York American and the New York Herald.

One thing, however, had already become clear: in the United States, comic strips meant big business and certain success. Among the great classics that were published in the daily pages,Krazy Kat (1913), Gasoline Alley (1918), Winnie Winkle (1920), Barney Google (1919) and Little Orphan Annie (1924) stood out. But the comic strip as an art form hadn’t yet reached maturity. It was still looking for coherence in its structure, language and dialogue. Some newspapers and magazines even printed their comic strips vertically rather than horizontally.

The Mannekensblad

While the US was engulfed by a creative fever, in Europe, everything remained strangely quiet. But this was merely the quiet before a great storm. In Flanders, the Mannekensblad (the Children’s Journal) was first released in 1911. It contained the first gags in Flemish, as well as illustrated texts and comic strips by W. Seghers, a cartoonist from Antwerp. The same year, another weekly children’s journal was born in Antwerp: Kindervriend (The Children’s Friend), featuring many French and British series. In France, in 1925, a certain Alain Saint-Ogan was making a lot of noise with Zig et Puce, while in the Netherlands, Frans Piët launched Sjors van de Rebellenclub (Sjors from the Rebels’ Club). Then, the Flemish George Van Raemdonck created, among other comic strips, Bulletje en Bonestaak (Bully and Beanstalk, 1922), a humorous strip making fun of bourgeois moralism, for the daily newspaper Het Volk.

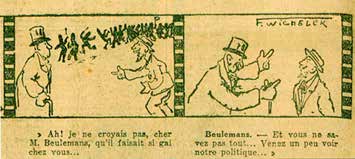

According to some experts, Van Raemdonck was the first Flemish comic strip artist. Maybe so, but this is also open to controversy. Who was the first Walloon, Flemish or Belgian comic strip artist? Which were the first Belgian series published in the papers? So many questions remain unanswered, and are still studied by comic strip theorists as well as university scholars. In 2012, Le Dernier Film (The Last Movie), by the Brussels filmmaker and director Fernand Wicheler, was dedicated to the first Belgian serial comic strip published in a Belgian newspaper. Between 1922 and 1926, 296 episodes were published in the French-speaking daily Le Soir. However, according to the strict definition that says a comic strip must include speech balloons, the film was not about a comic strip in the true sense of the word. Indeed, text and images were clearly separated, dialogue and narrative being written underneath the images. Remarkably, a quarter of a century ahead of everyone else, Wicheler addressed issues that would often come up in series such as Marc Sleen’s Adventures of Nero, delivering humorous social critique, attacking politicians in general, and Germans and Flemish nationalists in particular. Yet the series was also filled with strange creatures and animals as commentators.

Continue to Part 2

From La Belgique dessinée by Geert De Weyer