It took 75 years for comic books to begin breaking down the walls of discrimination that surrounded them, says Greg, editor-in-chief at Tintin. In the three quarters of a century in which comics were tarnished by an ill-deserved bad reputation, artists hid behind pen names and scores of talented youth were discouraged from making their path in an industry that the self-righteous condescendingly called literature’s “delinquent little brother.” In 1955, the Belgian Minister of Education even went so far as to draft a brochure for teachers and youth organizations, warning them about the problems and dangers inherent to comic books.

“One day when sociologists look back on us, they will no doubt wonder why some were so keen to label comics, and everything associated with them, as something that was ‘just for idiots.’” Greg, who was at this point Tintin’s editor-in-chief, thus launched his diatribe via a ten-page supplement called A look into the world of comics, published in October 1971, to mark the magazine’s 25th year. All the magazines that published comics at the time— including Tintin, Spirou, Pilote, Ons Volkske (Our Little Ones) and Junior—were pictured together on the front page, united for once in common cause.

Greg was looking to put a definitive end to the ongoing smear campaign that was carried out as much by the educational sector as it was by the public authorities. His mission, at this point, was hardly controversial. In fact, censorship was already on a steady path of decline all around. There was no one left to give him slaps on the wrist, or in the case of foreign countries, to threaten him to pull a book or a Lombard magazine from the market over accusations of moral decadency.

Greg opens his introduction with a strong quote from Hergé: “It is—hopefully—no longer the case that anyone should feel self-conscious talking about comics and their writers. After all, until recently, how did respectable society view comics? As a silly pastime for kids. Or worse! Low-level literature designed for the stupid. This description has well and truly been put to rest. Even the respectable now see the comic book as a new medium of expression, an innovative communication tool that, while not being a film itself, clearly shares attributes with the world of cinema. In the same vein, it is close to literature as well, while maintaining its own identity.”

Greg and Hergé are well placed to make such statements: they witnessed it all. The writers who launched their comics after the Second World War were made aware of people’s disdain for their profession often enough. “They definitely made their feelings known,” says Marc Sleen ruefully, as he summed up his career as an artist on the eve of his ninetieth birthday. “Comics were for morons. I’m talking about comics that were published right after the Second World War, when quality publications were few and far in between. We only had Mickey Mouse and a couple of others. It was Vandersteen and I who gave comics their start in Flanders.”

Perhaps—as Sleen was well aware—the series that circulated might not have been the best in the world, but the fact that they were published every day in the newspapers had sparked public interest. One thing he highlights is that the comic book coming into its own—initially in French-speaking Belgium, then slowly but surely across Belgium too—was a phenomenon wholly due to one person: Hergé. “He was already a towering figure in Belgium. Everyone admired his ligne claire style. He was part of the generation of great writers—in which I also count myself—who transformed comics from ‘reading for idiots’” to the ‘The Ninth Art.’ For me, there is no higher praise. I considered it a turning point. I realized it wasn’t about funny little guys stepping on banana peels. It was so much more.”

It took a while for comics to enjoy any sort of recognition. A good long while. It was acceptable to ask questions like, “OK, so you draw comics, but what do you really do for a living?” The art world, which made a clear distinction between high culture on one side and pop culture on the other, treated comic books as highly suspect. Those entering art school and announcing that they wanted to pursue a path in comics were systematically discouraged and steered towards painting or sculpture. In many ways, comic book artists were on the bottom rung. It’s thus of no surprise that a lot of them ended up hiding behind pen names.

It’s important to understand public opinion on comics at the time in Belgium. It’s not an exaggeration to say that, as of the early fifties, comics were considered to be a deviant form of culture. Even calling it a form of ‘culture’ was being generous. Comic book writers and readers alike still recall how in their younger days, comics were banned both at school and at home.

The Ninth Art

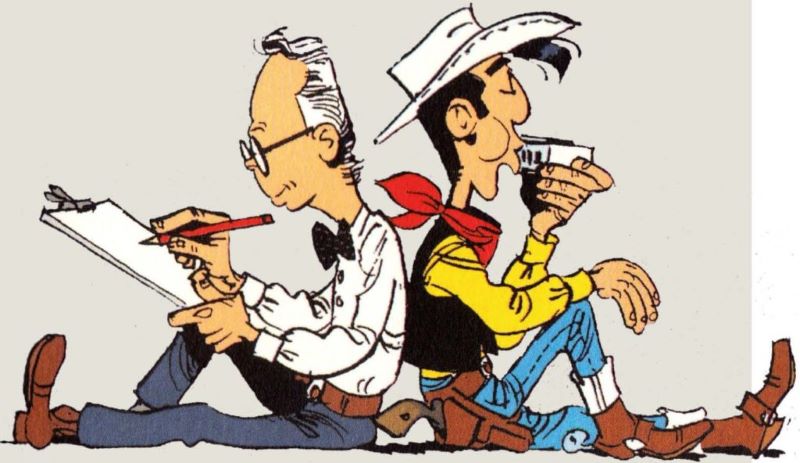

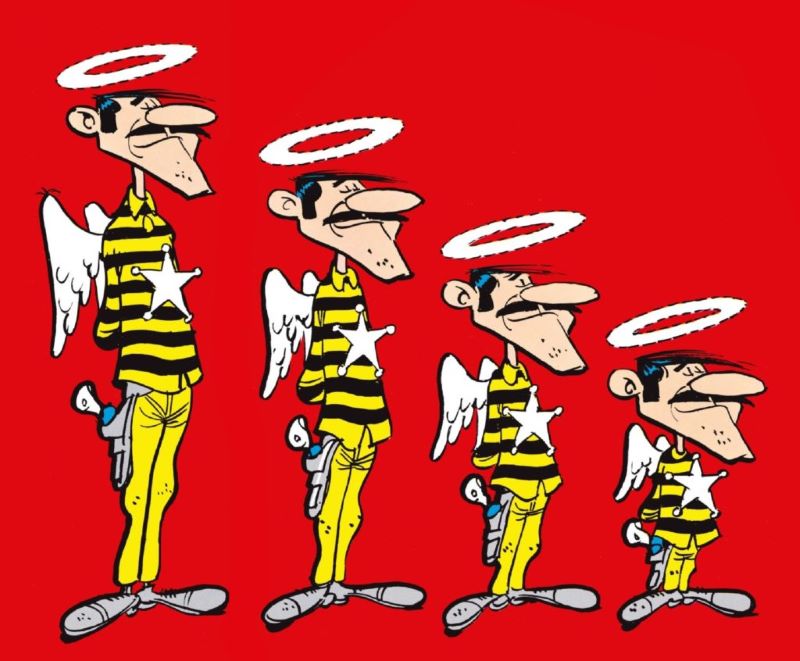

The inventor of the term “Ninth Art” is thought to be none other than Morris, the creator of Lucky Luke. He came up with the title Le Neuvième Art (The Ninth Art) as a heading, in fact, for his column on classic comics that he wrote for Spirou in collaboration with Pierre Vankeer in late 1964. Some Belgian experts note that, eight months prior to Morris’s column first being published, the term had been used in an article on the topic by Claude Beylie in the medical journal La Vie Médicale. What we can state with some certainty, though, is that Morris popularized the term internationally by spreading awareness to the public at large.

Can reading harm the young?

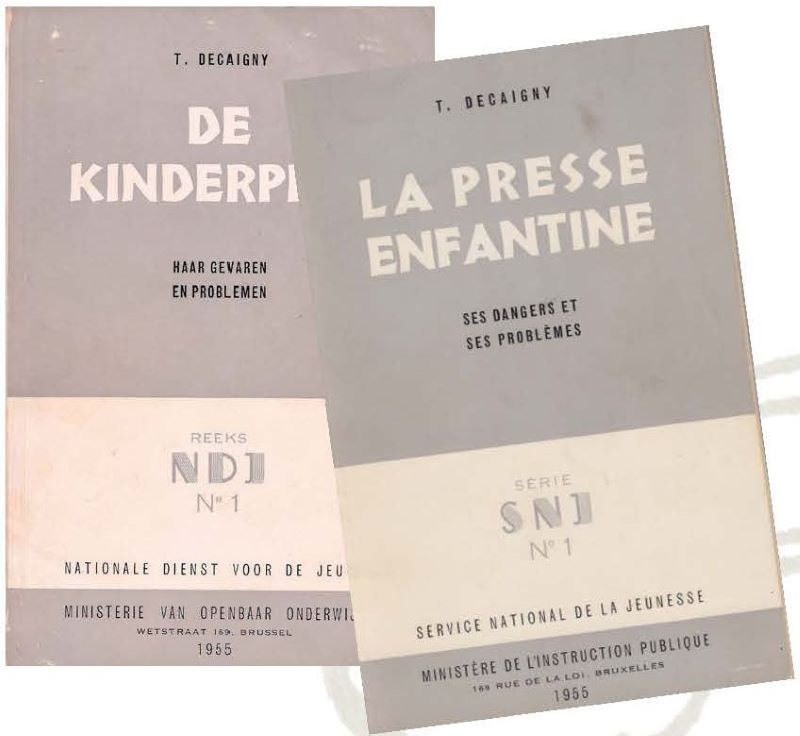

It’s hard to say whether this was a question that troubled the authorities. At the very least, we can say that it’s a debate in which they awkwardly interjected, and possibly even aggravated. To get an idea of the derision that comics had to deal with, look no further than the sixty-page pamphlet produced by the Belgian Minister of Education in 1955, titled Publications for children: the dangers and problems.

The pamphlet makes no mention of the proper title “bande dessinée,” which most commonly translates to “comic book,” instead making reference to so-called “comics,” “bad illustrated books,” “illustrated children’s books,” and sometimes more simply “picture books.” The author starts off by recognizing that research had shown few links between reading “comics and mental age, performance at school, the amount and types of reading and even socio-economic conditions.” That said, he asserts that “a lot of troublemakers seem to be very taken with these kinds of books.” And concludes that, in fact, “…the experts are not in agreement whether these books should be seen as the causes or symptoms.”

The leaflet makes ample reference to foreign studies on so-called “bad children’s literature,” suggesting that “the problem with [it] is linked to how kids spend their free time.” Decaigny, the author of the piece, plaintively explains that children can easily procure comics magazines, while modern literature remains out of reach. Comics can effectively be read anywhere, they can be folded and stuffed into pockets and, more importantly, they come cheap. One might well argue that films have a much bigger role to play than illustrated publications, but that argument is deftly neutralized by the author: “to those skeptics I say that a film is a short-lived and fleeting experience, whereas due to the use of imagery, ‘comics’ have a staying power that is equal to the former.”

The piece is somewhat ambivalent, at times seemingly in favor of comics, at others against, but it eventually becomes clear that Decaigny is no fan. For one, he refers again and again to measures that “protect children,” ostensibly following the position taken by countries like New Zealand, the United States, France, Portugal, and West Germany, as well as by Die Lektüre de Flegeljahre, a work he considered to be “remarkable” that had first been published in West Germany in 1955. But Germany had begun passing legislation on children’s books as far back as 1930. Wasn’t it all a bit much? Apparently not, as a comparison between the stats of the fifties and 1930 showed that “today’s youth currently read a lot more ‘comics,’ as though this generation has shifted down in maturity by a year or two, compared to youth in 1930.” And so, this same study concludes that a law “banning the sale of picture books to children under a certain age would probably be highly ineffective.”

In any case, restrictions like that would mainly hit small businesses and other middlemen—like distributors—instead of the primary target: the publishers, “who make immense profits internationally.” Immense profits? But of course! The author supports the statement by wielding a study conducted by the University of California, which shows that the comic book industry in the United States has a turnover of more than a hundred million dollars, “which is more than all grade school and high school textbooks combined.”

The criminal authorities also got involved. Critic Henri Wallon stated: “while these books are not the key source of juvenile delinquency, they can often provide the blueprints for it.” He added: “it’s not the trigger for the explosion, but it plays a part.” He then brought forth findings set out by the American Senate sub-committee that had been looking at the potential link between comic books and delinquency. Three points stood out.

First, if a child is well-adjusted, a reasonable amount of time spent reading “comics” is unlikely to encourage any sort of criminal behavior. The sub-committee highlighted, however, that the books might have a negative and dangerous impact on children with emotional issues, “who might respond to messages encouraging them to act out their pre-existing aggressive tendencies.” As a final note, the findings mentioned that “too much time spent reading these books is in itself a symptom of an emotionally imbalanced child.” As a result, the Belgian writer could only conclude that “by allowing children such easy pleasure, we are not only holding them back from pursuing active and morally sound pastimes, but also from engaging in thought and self-reflection.”

The “Bibliography and consulted works” section revealed an author very much affected by foreign influence. Of the 23 titles referenced, only two were Belgian. The rest came from Germany, the Netherlands, France, Great Britain, and the United States. Clearly, comic books suffered a bad reputation far beyond Belgium and Western Europe. More tellingly, Publications for children: the dangers and problems also cited The Seduction of the Innocent by American psychiatrist Frederic Wertham. This book received a warm welcome by some politicians when it was published in 1954, who were all too happy to take the prominent psychiatrist’s words on board in their crusade to lambast comics.

And Publications for children was just the start. One year on from the release of the edifying pamphlet, an article— very much along the same lines— was featured in an issue of Volksopvoeding (Public Education), a Belgian-Dutch magazine for socio-cultural sector employees. The Seduction of the Innocent served not only as an inspiration, it was also praised as an exemplary text on the topic. The call to action was simple: “immoral” and “dangerous” comics must be censored.

Ten years later, comic books were still being pilloried. In 1967, an article was published in De Bond—a weekly put out by the Bond van Grote en Jonge Gezinnen (Association of Large and Young Families)—calling for comics to be banned. Hundreds of thousands of families received the magazine in their mailboxes. Librarians, educators, and teachers alike were asked to purge comics from their literacy lessons. The effects of the article continued to be felt long after its publication. In 1988, Kristien Versteylen, a librarian in Antwerp complained about the decision to add nearly a thousand comic books to the children’s section, stressing that comics didn’t belong in libraries at all, and further arguing: “Whatever the fans seem to think, comics effectively cheapen literature. More than that, studies show that children who are crazy about Jommeke (Jeremy) or De Rode Ridder (The Red Knight) suffer from a delay in linguistic development.”

In the years that followed, libraries gradually became more welcoming to comics, whether these were in the form of commercial titles or graphic novels. Eventually, comics ended up having a separate section of their own. They even began to be promoted at conferences and traveling exhibitions. At this point, the Belgian Ministry of Education had a complete about-face in its approach. The comic book was no longer looked down on at all! More and more Belgian teachers began to use comics to teach diverse subjects, from history to philosophy. Experts were invited to analyze the medium, and, later, graphic novels started to be featured on school reading lists. All thanks to the Ministry of Education!

Modern art

And so, bit by bit, the comic book came into its own and entered the mainstream. Art critics, gallery owners, directors, and museum curators became increasingly taken by them. From the 1970s onwards, a distinction was made between mass-produced comics and those that were deemed to be “quality,” and all the while efforts were made to negotiate the gap between comics and “proper” art. Slowly but surely, comic book writers began using their pages to hold up a mirror. They experimented with various drawing and painting techniques, coloring methods, the length of their books, social and historical context, as well as character quirks.

They not only looked to other comic books for inspiration, but also other disciplines, such as sculpture or even photography. What used to be considered “little Mickeys” all of a sudden became a respected art. In 1978, for the first time in Belgian history, an exhibition on Belgian comics took place at the Palais des Beaux-Arts. The organizers were none other than Yvan Delporte and Franquin, with the support of Jean-Maurice Dehousse, the former Walloon Minister of Culture.

Comic books and literature

So had comics stopped being considered—to use the oft repeated derogatory phrase—literature’s “deviant little brother”? Had the perception finally lifted? In more recent decades, Belgian writers have drafted countless articles in praise of the comic book. In 2011, Stripspeciaalzaak.be—the largest online portal on comics in the Dutch language—launched a large-scale study to ask 150 Flemish and Dutch writers (as well as some French-speaking ones) about their relationship with comics. According to editor-in-chief David Steenhuyse, the participating writers came back with a broad range of favorites when it came to comic book series.

The spectrum covered traditional series like Suske en Wiske (Willy and Wanda) and De Kiekeboes, meandered across the Franco-Belgian school with Spirou and Fantasio, Astérix, and Tintin, and also included graphic novels by Chris Ware, Jacques Tardi, and the young Flemish writer Brecht Evens. “I think I owe my love of history, which comes across in my work, more to Willy Vandersteen than to Homer,” says Benno Barnard. Bart Moeyaert also calls himself a fan. When asked about the essence of comics, he responded: “Like in other forms of culture, there are series that are meant to be read quickly; these have no great literary ambitions. But one thing I’ll tell you and I’ll always stand by it: we have lots of comics and graphic novels that can well and truly be considered literature.”

Excerpt from La Belgique dessinée, by Geert De Weyer (Ballon Media, 2015).

Translated by Storyline Creatives.

The opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the writer, and do not necessarily represent the views of Europe Comics.

Header image: [Cover for: “Les Dalton se rachètent”] © Morris / Dupuis, 1965